Papers on Parliament No. 55

February 2011

Prev | Contents | Next

Everywhere, not just in the United States, we often turn to our government to try to protect us against political corruption, to prevent political corruption through the rules and regulations, laws that make it difficult for someone to do something corrupt. Some examples are laws against outright bribery. In just about every democracy in the world it is illegal to bribe someone directly, to buy their vote. For example, to buy a vote of a member of parliament. The secret ballot, which in the US we call the Australian ballot and around the world they call it the same, is intended to protect our right to vote the way we want to as individual citizens. That we not be bribed or intimidated into voting a particular way. Campaign finance laws are written and hopefully followed in an effort to prevent corrupt activity to unduly influence the outcome of an election or to have an influence in law making after the election, so I’m going to focus on campaign finance.

Any society that decides it wants to try to regulate the behaviour of human beings, whether we are talking about politics or the behaviour of business executives or how people act with one another in society, we tend to examine what is important to us. We focus on various values—things like liberty, equality, privacy, fairness—that societies hold dear but not always do we focus on exactly the same things in the same measure. In the United States almost always if you look at the way we approach how we try to regulate behaviour by human beings, corporations, politicians, interest groups, parties or whatever, we tend to put the value of liberty above all other values and I think this will become a little more clear.

One of the ways to look at it might be to look at, for example, the United States as one of the biggest—probably the biggest—advanced democracies in the world. It is the one country that is probably the least furthest along towards the idea of equality in economics so we are firmly still in sort of the laissez-faire economic system as opposed to other countries. Certainly we have socialist sorts of programs, so away from complete laissez-faire or no government intervention in the economy towards things like social security for the elderly, Medicare for the elderly, food stamps, welfare payments for people who are out of work or poor etc. There are certain things that we’ve moved in that direction but compared to other countries, like most of the European countries and Australia, we have not moved as far down that path. One of the reasons is because of our focus on liberty and if you go back to our original documents, the Articles of Confederation and our Constitution, for example, you see this importance of liberty. We believe it’s important in the United States, for example, that we have freedom from things more than freedom to do things and that’s a kind of a hair-splitting distinction. However, if you look at it in terms of rules and regulations or laws passed by the government, freedom from government regulations. So if you look at environmental laws, for example, corporations and businesses will say ‘We don’t want to be over-regulated. We want to be free from government regulation so that we can continue to exist. If we can’t turn a profit we can’t continue to exist. If you over-regulate us it’s going to cost us too much to protect the environment so that we won’t have a business any more’. So these are tensions that we see in all types of policy areas. Freedom from government intrusion into my own life. Don’t tell me what I can do in my own bedroom, my own living room. Don’t tell me, government, what and how I should be living my life as long as I am not harming other people, I shouldn’t be stopped by the government.

My argument about campaign finance is that currently and pretty recently, in particular, the ability to prevent corruption in the United States is limited by our interpretation of liberty. In particular our Supreme Court’s interpretation of liberty and how they apply the idea of liberty. That this interpretation constrains the United States Government’s ability to ensure political decisions are made in an environment free from corruption. So political decisions like how we vote on election day, political decisions like how members of Congress will vote when they get to government—those are the kinds of political decisions I mean.

Just a little bit of background because everybody’s coming from different places about some things that are different in the United States. In the United States every lawmaker is elected independently. What that means is that every person running for the House of Representatives, the Senate or for President of the United States, for example, is running their own campaign. The party’s not running their campaign for them, the party may assist them but in the United States currently the parties really don’t participate in too many of the races for Congress, for example. Each one is independently elected which means they are raising their own money and spending it themselves. There is other money going through the election system, and I’ll talk about where that is coming from too, but they’re pretty much responsible for their own election and re-election.

We have single-member districts with the winner take all system. We don’t have a preference system or any of that. We have a first past the post system which pretty much ensures, although not absolutely guarantees, that you have a two-party system which we’ve had for a very long time. With a few minor parties every once in a while gaining some strength but for the most part not being able to achieve majority status by taking over government for example.

Candidates don’t need the party to win because in the late 1800s and early 1900s the political parties had very important powers stripped from them and that was the power to nominate their own candidates, so now candidates are nominated through primary elections. It’s just like a regular general election, but held before, so that voters from each party will select themselves who is going to run as the nominee from the Democratic Party or the Republican Party. These primaries are really disputes within the party. Who’s going to run? We’ve got two, three, maybe four people from the same party running against each other to determine who the nominee is going to be. The political parties themselves tend to stay out of those family feuds because, really, they’re not going to choose favourites over people who are all from the same party. It doesn’t always happen. Sometimes, of course, the party establishment has preferences about who they’d like to see win and usually it’s the person who they think can win the general election when they go up against the person from the other party. Yet, for the most part candidates are on their own in the primary elections as well.

As I’m sure you know voting is not compulsory, it’s voluntary and that means a lot of different things. One of the things it means is during the elections most activity—whether you’re talking about the candidates, political parties, outside groups, unions, corporations, everyone involved in elections—is focused on turning out the vote. Not necessarily getting the most people to vote but getting the right people to vote. If I’m running for office I’m not going to try to mobilise your people and if you’re running against me I want my people, but I want a particular set of people. People I know who are members of my party because they’re registered, for example. People who I know have voted in the past. People who I know other things about—they have all kinds of sophisticated data sets so they learn all kinds of stuff about us. The focus is not necessarily on the biggest turnout but just the right turnout—enough to get you elected.

Finally, Supreme Court justices (and this will be important when we talk about some of these court cases) are not elected but appointed by the president, approved by our Senate and they serve for life so they are there for a long time (most of them).

Just a little bit of history so we can get to the present. As early as the 1860s some of the states in the United States started passing regulations to curb primarily the activities of corporations in their campaigns and then on the federal level we started to see in 1907 the same kinds of activities. All of these reform efforts are attempts to pass laws to regulate people’s activities and behaviour in campaign finance. It generally came in the wake of scandal so something bad would have to happen. Teddy Roosevelt was accused of having the corporations front his campaign and that is why he became president, and he really came under a lot of attack and so he championed finance laws. He got the Congress on board too, although they were ready to go after him, actually, and they banned corporations from participating in campaigns. So that’s how most of it started off. Between 1907 and 1947 we see some important principles established in the law. First, and maybe quite importantly, because it may be the only thing we end up left with after a few years, is that we have a pretty robust disclosure system that candidates and political parties needed to disclose everything that they were taking and spending on a quarterly basis. Anything over $100 back then was a lot of money but the idea here is that the principle was established very early on.

Spending limits were instituted for parties and their candidates. Even way back then they were saying there is too much money in politics. One way to try to reduce the amount of money out there with people maybe having too much influence over the outcome of elections is to just not let them spend too much and so spending limits was another principle that was put into the law pretty early. And then there was this ban on corporate and later union contributions and spending. The union ban came in 1947 and was a reaction to the growth and the strength of the union movement and their participation in elections. The ban on corporate participation started way back in 1907—that was the very first law on the federal level. These are some principles that go way back so they have been in the law for a long time. The problem was that they weren’t enforced. There was no agency established to regulate them, to look after people to make sure they were following the rules. People could easily evade them. It wasn’t clear who to report disclosed information to so even though the laws were on the books it didn’t really matter.

In the midst of, before, and after, probably one of our biggest scandals, the Watergate scandal—I’m sure some of you have heard of that one—we passed the biggest campaign finance reform legislation we’ve seen in the US called the Federal Election Campaign Act. It was originally passed in 1971 with amendments in the wake of Watergate in 1974. It did a number of things. First it sort of reiterated in many ways what the previous laws had tried to do but tried to do this with some teeth so that it would actually be enforceable. Donations were banned from corporations and unions that had already been on the books. They added banks, government contractors and foreign nationals. This was particularly important in the midst of the Cold War in the wake of red scares etc. It wasn’t that there was a fear that the communists were going to come in and take over our politics but the idea that the United States, and nobody else but the United States, should be running our own campaigns. The idea of adding foreign nationals to this was an important one that has stayed in the law since then (an important addition).

Again, quarterly candidate disclosure of contributions and expenditures was reiterated with teeth behind it so that in fact there would actually be disclosure. We’d be able to figure out what was going on. Because the disclosure is quarterly it happens before the election. I’ll get to that when we talk a little bit about Australia at the end. I think that one of the most important lessons that a lot of countries might take from the United States is that the voters know what’s been raised and spent before we actually go and vote on election day. That’s a really important element. It’s something about elections and our politicians that gives us more information about them.

Voluntary public funding for presidential elections was instituted for the first time and it was tied to spending limits. So in the United States the idea is that you can’t force anybody to take public money. ‘If you want to throw me money that’s great’, but if you are trying to limit the amount of money in politics, one way to do this is to provide public funding so you don’t have to go out and raise more money. In order to make sure that they don’t just raise and spend more money on top of that, get the candidates to agree to spending limits so the two are tied together: ‘We’ll give you public money if you agree to limit your spending’.

Just a few more points with the Federal Election Campaign Act. Contributions were limited to candidates from themselves first. This law said that you cannot spend all the money you have in the world, even if you are a billionaire, to get yourself elected to office. Contributions from individuals to candidates were limited. You can only spend so much money. You can only give so much money as a donation, a gift to a candidate to run for office. Remember, in the United States almost all the money is going to the candidates themselves, not to the political parties, although they raise a good deal of money too. Contributions were limited to the parties. The idea here is that the most severe or serious avenue for possible corruption was the candidates themselves—giving them a lot of money to run for office, them getting elected and them voting the way you would like them to vote because you’ve sort of helped them get elected. The parties, too, could have great influence over the way the candidates would vote once they got into office. This was seen as the potential for a quid pro quo kind of corruption and limiting contributions to candidates and the political parties was seen as important, in particular for that reason.

Then the Federal Election Campaign Act created a brand new kind of entity that we call a political action committee and it said ‘Everybody can participate in elections, even corporations and unions, but if you are going to do it you have to do it according to these rules’. These rules are that you must set up this thing called a political action committee, you can only raise money in limited increments and you can only give money in limited increments to candidates and political parties. This was an attempt to regulate how the money flowed, where it came from and where it went to and how it was spent and this was all, of course, disclosed. The Act also attempted to limit spending by the candidates themselves so to put a cap on how much they were allowed to spend overall. It also limited independent spending. So let’s say you are running for office but I really don’t want you to win and so I am going to go out and spend my own money, maybe I have millions of dollars to spend on this, I am going to go out and spend my own money to try to make sure you don’t get elected. Or if I belong to a group that does the same thing. The Federal Election Campaign Act attempted to limit that as well so that nobody’s voices are drowning out other people’s voices. You can see here this emphasis on equality, getting everybody sort of on a level playing field here. And then very importantly it created the Federal Election Commission. This is an agency that only deals with campaign finance, that’s it. They don’t run elections; they don’t do any other jobs. Their job is to make sure people are following the rules. Their job is to take in all the information that’s given to them through disclosure and to make it publicly available.

So up to this point we have some principles that are pretty much now carved into the law and have some bite to them so we have a commission now that’s going to make sure the law’s enforced and we have some real penalties in place so that if you break the law there’s actually something bad that can happen to you but hopefully that will serve as a deterrence more than anything. The principles are in place so that corporate and union contributions are banned to prevent corruption. The whole idea is that these guys have the most money and if we allow these very wealthy groups of people to participate in our elections they will very quickly override the interests of the regular citizenry. So this is the idea behind this principle: that candidate, party and group spending would be limited. So that’s to try to reduce the overall amount of money in politics and to try to sort of equalise that playing field. Overall the government’s interest is in preventing corruption and so in order to prevent corruption the government is justified in regulating or intruding on people’s freedom because it’s important enough so the interest in preventing corruption is more important than liberty in certain cases. That’s the justification for these rules and regulations.

Not too many years later, by 1976, the entire act is challenged in the US Supreme Court and the court does a very interesting thing. They say not all of this is going to work and they really turn to the value of liberty and they say ‘We’re going to look at both contributions and expenditures here and we’re going to look at them differently’, whereas in the law you haven’t really distinguished between the two. We’re going to say yes, it’s important that you limit contributions to candidates because they’re the ones who are going to get elected and then go on to vote on public policy, and we don’t want to leave them open to bribery. So you should limit contributions to candidates to prevent corruption or even the appearance of corruption. Limits on candidates and individual independent expenditures they say are a violation of the First Amendment right—freedom of speech. This is the very first right in the Bill of Rights. It’s seen as primary, quite important. In this case the court applies it to the area of campaign finance, really for the first time in a clear way. They distinguish between contributions and expenditures and say you really can’t gag someone, you can’t stop, even candidates from spending as much as they want to spend on their own races, or individuals who just happen to have a lot of money. By telling them they can’t spend that money you’re violating their right to freedom of expression, and so after 1976 in the Buckley v. Valeo case we see the strong connection between campaign finance regulations and freedom of expression.

The First Amendment deals with other things like freedom of religion, freedom of the press and one of the most important things is this freedom of expression and freedom of speech. The First Amendment right to freedom of expression has since 1976 really shaped our view of campaign finance and now campaign finance is all about money and so this decision was highly criticised and continues to be criticised today. The criticism comes primarily from people towards the left end of the political spectrum but not necessarily always. The justices on the Supreme Court did not say money equals speech but this is the accusation: that the court has equated money with speech which then allows those with the most money to speak the loudest in the name of liberty. We’re doing all this because we want to protect people’s liberty, but the consequence of that protection of liberty is problematic so that’s the criticism out there and it remains a very prominent criticism, particularly recently.

So what do we have after the Federal Election Campaign Act and the Buckley v. Valeo decision? Contributions are still limited to candidates and political parties and that may, as was intended by the lawmakers and the Supreme Court, actually prevent some corruption so that may be considered a good thing. Extensive pre-election disclosure allows for accountability. Now pre-election, as I said before, we consider pretty important because we think that this is information that voters should know about. It’s in addition to everything else you might know about a candidate. Where does this candidate get his or her money from? Who’s funding this campaign? Who might they be listening to once they get elected? Those are the kinds of questions that we’re concerned about when we say that pre-election disclosure is important. One of the consequences of all this disclosure and all the data that is available virtually 48 hours after it’s filed with the Federal Election Commission—now all on the internet, very easily accessible, anybody can go there and look at it—is that we have a very informed media. We have a lot of journalists who understand the data, and its reams and reams and reams of data. If you understand how to look at it you can really draw some important conclusions about what’s going on, and so the media has been sort of trained to be more attentive to this information and it has become part of the reporting on our elections.

We also have a number of very active watchdog groups that use the data and the information that’s disclosed to sort of call out ‘what’s happening with this? Are there certain industries or businesses or groups that are playing a big role or are they overshadowing other groups? What kinds of things? How much money’s being spent?’ And they are always putting out press releases and reports that too become part of what the public receives through the media and by these groups. We have a very low disclosure threshold compared to a lot of countries. If you as an individual give $200 to a candidate or political party as soon as you reach $200—even if you give it $10 every day for a few days—your contribution will be disclosed. So $200 is considered a pretty low threshold if you’re going to participate. Even at that low level people are going to know about it. It’s not a private act.

Then there are some not so good consequences as a lot of people argue all the time ... this is what you always hear about politics in the United States—there’s too much money. Yes, there is a lot of money in United States elections. Figure 1 is an illustration of money in the last presidential campaigns. You can see the blue line is the money that the candidates took in and so the trend is obvious. It’s gone up since 1996 and if you looked before this you would see the trend was going in exactly the same direction. These are just the last few presidential elections. The small bit of money at the top (it looks small but it’s $240 million so that’s a lot of money) is all the money that’s raised and spent by anyone other than candidates—political parties, interest groups, various individuals who want to participate. So put that all together and we can estimate, and I say estimate for good reason, it was about $240 million in the last election. This is an area where we are not capturing everything through disclosure because, as human beings will be human beings, people find ways around the law. As soon as you pass a law somebody’s going to find a way to get around it and many groups in particular have found ways to raise and spend money that isn’t required to be disclosed. The law makers try to keep up with human behaviour and sometimes they capture it and sometimes they don’t, so this figure at the top, the green money, is not quite as accurate as the money the candidates have to disclose. They do disclose. We know everything that is going on, hopefully, unless they’re really bad and they’re just violating the law outright. There’s no reason for them to. The punishment is pretty bad, so hopefully they are deterred. One of the consequences as well, not only do we have a lot of money, but what I like to think of is really where’s the money coming from, how’s it being spent, where’s it being distributed, what consequences does it have for things like governing or the electoral system?

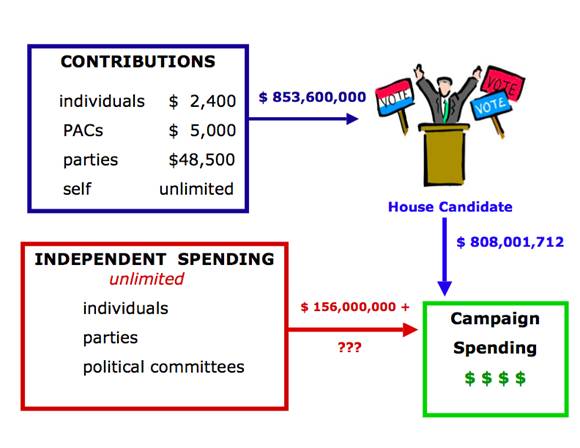

Figure 2: Limits on campaign contributions for House candidates

One of the things that happens is we don’t have a lot of competition. Very few races are actually fought competitively. Most people win by very large percentages and so I just want to explain how the money flows in a typical race for the House of Representatives. In figure 2 there’s our candidate up there so happy getting ready to win his election and so what can he do, how much money can he take in from what sources and how can he help himself get elected? He can take from each individual up to $2400 per election so that means $2400 for the primary election, if he has one, and $2400 for the general election. That’s the limit. That’s as much as somebody like you and me could give to an individual House candidate. From a political action committee he can take up to $5000, again one for each election, so that equals $10 000 if he’s getting money for both the primary and the general election. It looks like he can get all this money from his political party but what you have to know is that although the party can give a candidate directly almost $50 000, the party doesn’t really do that very often and just concentrates on those very few close, marginal races.

The Supreme Court overturned that limitation on self independent spending and so the candidate now can give him or herself as much of their own wealth as they want. They said that that would be a violation of their liberty, the freedom of speech of an individual candidate, so if I happen to be a billionaire and I want to spend all that money running for office I’m allowed to do that. The Supreme Court said that that is okay. We see some examples that people find very disturbing in the United States. Quite recently Carly Fiorina, who’s running for US senator in California, the state that I come from, just gave herself $39 million to run for the Senate. That’s a lot of money. California’s broke right now. I wish she’d just transfer it over to the Treasury, it would help. We will see how that one turns out in November.

Other money comes from other sources. People can spend independently, parties can spend independently and political committees—I say political committees rather than political action committees because it encompasses political action committees and these other groups—some of them have found ways to raise money and spend it without having to disclose it. That’s why that figure of $156 million has a big bunch of question marks under it because we’re not sure if we’re capturing all the money through disclosure and we know we’re not. Here’s how much we have captured and if you look at the amount of money raised by all the candidates and that figure $853 million is all the candidates, all 435 seats where there is usually at least two candidates. That’s all the money raised by them and then they spend $808 million. Some of them still have money in the bank at the end of the election and all that money is being spent on elections throughout the country and not all in one place and you can see it is a lot of money. But here’s where it comes from and here’s how these things are funded. The contributions that candidates get, remember, are limited except for the money that they can give themselves. If I spend a lot of money to defeat someone or help elect them, or a political party or a group decides to do that, we can spend as much as we want. Those aren’t limited.

So where does the money from just the contributions come from? Most of it comes from individual, regular people who write limited contribution cheques to candidates—that’s 54 per cent (see figure 3). Thirty-six per cent of it comes from political action committees. So that constitutes about 90 per cent of it is coming from these two sources. One per cent, hardly any of it, is coming in contributions from the political parties. The parties choose to spend their money independently. That means they’re not talking to the candidate at all. They’re out there running ads primarily and trying to get their people elected or trying to defeat the other party’s person. So the money they’re contributing, writing cheques to the candidate, is only one per cent. Most of their money they spend independently so that they can spend in an unlimited fashion. Candidates are spending a lot of money on themselves—six per cent—that’s a lot of money. The other category is what I call the ‘sad category’ because it’s really sad that some people do things like take out second mortgages on their homes to run for Congress and those sorts of things, take out loans from their uncle. That’s that category. It’s gotten bigger and bigger with the years. This chart is for 2008. This is where the money is coming from going directly to candidates and in the form of contributions.

As I said my concern here is that competition is diminished. That we don’t have very competitive elections which are seen as important in a democracy, because if I as a voter don’t have a choice between at least two candidates, how can I say that I am really playing a part in my democracy if I don’t have a choice, if one person is always going to win no matter what and the other one is just a sacrificial lamb? Why should I really feel that I play any kind of part in elections? The lack of competition or very little competition is seen as a very unhealthy thing in most democracies. Only 16 per cent of our 435 races for the House of Representatives were won with 55 per cent or less of the vote. Now that is seen as pretty competitive—55 per cent. The other person gets 45 per cent. The number is not much better if you go up to 60 per cent and so most of our elections are not competitive. The person who is going to win is pretty much known. Watch elections coming in November 2010, you get pretty good coverage of that here. You’ll see that we probably have more competitive elections than we have had in a while. In part because politics is pretty controversial now and there’s a lot of disagreement with what the party in power is doing in Washington and so there might be some more interesting races and therefore more competition.

Sixty-seven per cent of all contributions go to incumbents. Those are the people who already hold the seats, so they also have a lot of other advantages. Incumbents get more media attention. People generally already know their names—at least more so than they know the person who is running against them. They already have a lot of advantages and they get the most money. That’s a huge advantage when running against someone. Lawmakers always complain that they're spending all their time raising money and for the House of Representatives it’s probably true that they spend a lot of time raising money. The House races are only two years apart, so as soon as you get elected you’re facing another election in two years. That’s not very much time to get ready to raise, in most cases, millions of dollars. Remember, you’re raising it in limited chunks, limited increments.

If we look at the trajectory over time (figure 4) you can see the pattern is obvious again, it keeps going up. This is the average expenditure by House candidates over time since 1996. The trend is primarily that, ‘wow, look at that blue line. Those people are spending a lot of money’. Well, those are the open seats. Those are the races where there is no incumbent so somebody has retired or died or moved on to run for another office, something like that, and so neither of them have those incumbency advantages. They also tend to be the only races sometimes that are even competitive and so lots of money is poured into those races. In 2008, however, there were only 41 of those races, so that big blue line constitutes only 41 out of 435 races. That’s where most of the money went, so it’s kind of an odd thing right there. The rest out of the 435 are challengers versus incumbents, and so as you can see the incumbents are the green line, the challengers are the lavender or the pink line and the incumbents almost always outspend their challengers. Overall these are averages. If you look at individual races you will often find that there are challengers who spend more than their incumbents. This doesn’t mean that they are going to win necessarily. Just because an incumbent spends more than the challenger doesn’t mean they’re going to win but money is important, so if you just look overall at the averages you can see that in fact money is not distributed at all evenly among the different people running for office and the consequence is that over 90 per cent of incumbents win their re-election contest, so that’s not a lot of competition. Again, this is usually seen as a kind of unhealthy thing in a democracy.

Another issue, and this is a fairly recent one, is that this outside spending—that unlimited amount of spending that can be done by political parties, groups and individuals—is now outpacing, in some contests, the money that the candidates actually raise and spend themselves. Now this is happening in these very few competitive races all because that is where everybody is concentrating on this opportunity to either pick up a seat for your party or to maintain that seat if you already hold it. I just took two cases from the last election. In Minnesota, in this case the third congressional district, the outside groups, political parties and individuals spent 52 per cent of all the money spent. Candidates only spent 48 per cent and so the candidates were outspent by these people who weren’t running for office. Remember the candidates are the only people who appear on the ballot on election day. Their names are there, they’re held accountable for what happens during the election. So if negative ads run that the voters don’t like, even though the candidate might say ‘Hey, I didn’t run it. That group called Citizens for a Pretty America ran it. It wasn’t my idea’. It doesn’t matter. Voters tend to not like negative advertising if it’s way out of whack and they will blame the person who seems to be helped by the negative advertising. Candidates hate this outside spending because they get blamed even when they don’t misbehave. Even if they don’t run negative ads, people trying to help them get elected aren’t doing the best favour for them. It often backfires.

Figure 5: Outside spending limits accountability

|

|

|

Outside spending (US$)

|

Candidate spending (US$)

|

|

MN

|

3

|

$6 004 387 (52%)

|

$5 632 148 (48%)

|

|

MI

|

7

|

$5 873 605 (57%)

|

$4 473 491 (43%)

|

Source: Federal Election Commission, ‘Congressional candidates raised $1.42 billion in 2007–2008’, News release, 29 December 2009

In Michigan, in the seventh congressional district, we saw a race where these outside spenders spent 57 per cent of all the money. The other thing to remember about the outside spending numbers is that this is only what we know about. We know about candidate fundraising and spending. They have to report all that and there are not too many ways they can get around it. With outside spending, this is only what we know so the numbers are probably even bigger. The candidates’ voices, if you also track the campaign ads on TV for example, they’re really outspent and outmanoeuvred on television and on radio. If you count the number of minutes, whether it’s a negative ad or a positive ad, where people remember the ads, people do research like this so they know this stuff. Sure enough the candidates’ voices are often quite drowned out. They know more about the ads that the other groups or individuals are running, for example. So this is seen as a real problem because it limits accountability. These people come in to your election, they spend a lot of money but they don’t appear on the ballot on election day, they don’t get held accountable for running very negative campaigns, almost always they are negative campaigns. If your group is not going to be held accountable you don’t have anything to lose. Hopefully you want your guy to win but they’ll tend to sling a little bit more mud than will a candidate who knows that it is going to come back on them. So there’s a lack of accountability as the candidates’ voices are drowned out by others.

Another problem of consequence is that although the public funding system did work for quite a number of years, we’ve seen quite recently, and this is just an example from 2008, that candidates now realise they can do better without taking the public money. The public money used to be seen as quite a good thing. It’s very helpful. You don’t have to spend all your time raising money. You get all this cash and then you agree to limit your fundraising and spending after that point. It worked pretty well up until 2008 when Obama decided not to take the money—it was quite controversial—and McCain did take it and there was a large disparity between how much each one had to spend on the election ($350 100 000 for McCain and $745 700 000 for Obama).[1]

Then in January 2010 everything changed or at least potentially changed. There was a big lawsuit that made it to the Supreme Court in January and was called Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission (2010). Remember it’s the Federal Election Commission that’s in charge of all this. The agency is in charge of campaign finance on the federal level. Anytime somebody wants to challenge some part of the law they sue the Federal Election Commission so that’s why they’re named in this suit. The court said the case is about a non-profit corporation that wanted to be able to spend as much as they wanted to influence the outcome of elections. The court said, ‘well, the law currently says the corporations can’t spend as much as they want to’. Those things are limited. Corporations are not permitted to participate directly in campaigns. They’re supposed to form political action committees and limit their income and their output.

But the court said ‘no, we’re not going to look at it that way anymore’, so they changed their minds. They said ‘no, that law is invalid. It’s unconstitutional’. In fact they say the government may not suppress speech, because remember this idea that freedom of speech is what’s under contention here. The government may not suppress speech on the basis of the speaker’s corporate identity. ‘You shouldn’t be distinguishing’, the court said, ‘between a corporation and an individual, you shouldn’t discriminate against corporations in this way’. They said these independent expenditures, including those made by corporations, just don’t give rise to corruption or the appearance of corruption so they’re just stating that this is not a problem with corruption. There is no potential for corruption here so we don’t have the justification to regulate in this area. There is no government interest that justifies limits on the political speech of non-profit or for-profit corporations. For a hundred years the court has upheld laws that have said corporations actually should be limited in their ability to spend on federal elections, and so in January 2010 the court says ‘no, because we don’t see that as a potential avenue for corruption’. It’s quite a U-turn in a lot of respects.

Many people were critical of the issue. President Obama was one of them. He said that the Citizens United case will ‘open the floodgates for special interests ... to spend without limit in our elections’. So the concern again is that you’re allowing those who already control a lot of wealth to be able to have more of a larger voice in elections. ‘I don’t think elections should be bankrolled by America’s most powerful interests’, Obama said. This is very consistent with a lot of the criticism that we’re hearing from primarily, again, the left side of the political spectrum but not exclusively. On the right side of the political spectrum there has been a pretty long-standing effort to try to erode a lot of the regulations to deregulate campaign finance very much along the same time line as we’ve seen attempts to deregulate the regulations of business practices. We see it beginning in the 1980s through the 90s and to today, and this case Citizens United was part of that effort to deregulate, to stop the regulation of or limitation on political fundraising and spending and so many conservatives hailed this as a good decision and say this is the direction we should be going in because, in fact, this means more liberty for people and in this case for corporations. Those are the two sides. The Supreme Court overturned previous laws and court decisions that had very clearly established this. One hundred and two years of prohibitions on corporate electoral spending. That’s a long precedent for them to make this change.

On the heels of Citizens United came another case at the end of March. Again, really recently, just weeks ago, and the court—this is not the Supreme Court, this is the lower court and I would assume that this case is probably headed to the Supreme Court. It’s SpeechNow.org v. Federal Election Commission (2010). They sued the commission to try to get this case into court. SpeechNow.org is an organisation that was created exclusively to challenge the campaign finance laws in the United States. That’s the only reason it exists. It’s an office full of lawyers and they sit around thinking up cases. That’s what they do. The DC circuit court heard this case and they said ‘Ah, this case is about contributions, the last one was about expenditures’. The court said we can’t limit the amount of money corporations—non-profit or for-profit—can spend in elections. This case and SpeechNow, they brought a case about how about the money we can raise as non-profit or for-profit corporations.

The court said limits on individual contributions to independent expenditure groups are unconstitutional. They’re saying that, too, is unconstitutional. We’ve had all these limits. Again back to the political action committee model. If you want to raise money to participate in elections you’ve got to do it in limited increments. The court is saying ‘no, no longer. We are changing our minds about this. We’re saying no, these limits are unconstitutional as well’. Since the expenditures do not corrupt, that’s what Citizens United established, neither do the contributions that come into the groups. It allowed them to make those expenditures, so it’s saying ‘no corruption in, no corruption out’. That the money coming in can’t be corrupting because the money going out we’ve already determined, the Supreme Court said, isn’t a potential for corruption. So they concluded ‘the government has no anti-corruption interest in limiting contributions to an independent expenditure group’. So now the courts have looked at both sides of the equation. The money being raised by these profit and non-profit organisations or corporations and the money being spent by them and basically saying limits on that in any way are unconstitutional, a violation of freedom of expression.

This new interpretation really limits our ability to prevent corruption. The court has said, and clearly I disagree, that this is not the potential for corruption that everybody is so worried about, so maybe I’m just a nervous academic that sits around worrying about these things. But a lot of other people do as well and the idea here that the only entities that are now really regulated by law are the candidates and the political parties who still must raise money in small increments and spend it in limited increments. If they are limited in that way but everybody else who can participate in campaign finance is not limited in that way, then I think that you can tell what we might see in the future in our elections. Remember it’s the candidates who are held accountable on election day because their names appear on the ballot. The political parties, their label appears next to them, they are the ones who we’re really focusing on. That’s who we send to government. Everybody else who is attempting to influence elections is pretty much free to raise and spend money with very little regulation. Now they do have to disclose this although it’s still being worked out exactly how we’re going to make sure we capture all that.

So, now, what’s going to happen? I think it’s fair to say that outside spending by profit and non-profit corporations will increase in future elections. That’s something I would actually put money on. I think that that might happen. One thing that a lot of lawmakers have anticipated and of course are not happy about is that corporations may come to them and shake them down and say ‘Hey, we have a big vote coming up on this oil drilling thing. We need you on this one. Hey I know the public is really upset about oil rigs right now but we really need you on this vote and we’re prepared to let you know exactly what we will do in the next election if we don’t have your support for this. Here’s a script for an ad that we’re getting ready to run against you’. They never have to run that ad, they don’t spend a penny on it, they don’t have to do anything but they can use their potential to spend unlimited amounts to ‘shake down’ lawmakers to get them to go their way. That was a kind of exaggerated example, but this is something that has come out of the mouths of many lawmakers, that this is a concern. Conservatives and left-leaning people as well.

This is a very highly organised effort by conservative groups and it’s been going on for a couple of decades. There are many, many more lawsuits in the pipeline. Things to try to not put any limits on any fundraising or spending and so some people say ‘well that would be good because then the candidates and parties will be on the same level playing field’. But, boy, watch how much money ends up being in elections. You have to decide what is important to you as a society. Some of the lawsuits also involve lowering disclosure. There is an argument that—and I have heard of this in Australia because many of you probably know that the campaign finance reforms are being considered here too, both at the federal level and in many of the states—people shouldn’t have to disclose when they make a campaign contribution because it is an invasion of their privacy and maybe they will be harassed for that or something. That’s some of the stuff coming through our pipeline. That is evidently an issue in Australia as well.

I’m going to dare to make a few suggestions, some lessons you might learn from the United States here in Australia. I have read all kinds of things and talked to people about the efforts here on the federal level. I know things are stalled in the Senate but most of what I propose is not controversial really but doesn’t mean it’s going to become law either. I haven’t seen too many people, except for a few scholars out there advocating this idea of pre-election disclosure. The United States is not unique in making sure its citizens know about the money that’s coming in and out of campaigns and what’s being spent but certainly we have a very well-developed effort to do that, so as I said, the information is available very soon after it’s filed with the Federal Election Commission. We have a pretty well-trained media that concentrates on these kinds of things and at least makes this information known and groups that keep an eye on how the system’s being run so we know what’s going on. By not having that kind of pre-election disclosure, if you find out ‘oh my gosh, the mining companies supported the party and that’s why they got elected—they got billions of dollars from them after the election’. If you find that out after the election, what good is it? Maybe it might influence somebody’s vote. If you’re not concerned about where the money comes from you don’t have to pay any attention to it. It’s a public act to give money to candidates’ political parties and it’s not publicly known until after the election. Election day is really the only day that it matters. The next time you are going to be able to hold people accountable is the next election.

I would also say consideration of limiting contributions. There are proposals out there to do that. Not at the federal level but the idea that if in fact there is a recognition that this is a potential avenue for corruption, particularly the most nefarious quid pro quo ‘I’ll give you money if you vote my way’ kind of thing, then limiting contributions is a way to do that. You don’t want to make contribution limits too low because then of course all anybody’s doing is spending their time raising money and there’s not going to be a lot of motivation to participate. If they are too high then a limit doesn’t have any effect so finding that balance is important.

Limit or ban foreign donations right now in Australia. Foreigners—foreign people, foreign entities or corporations—are permitted to participate financially in your elections and all I can really say about that is why? I’m not sure why that’s important, and why would you want money coming in from other countries? There have been some hints that that has already happened and when a million dollars comes from some Lord in England and comes to Australia that’s a lot of money going from one place to another and what interest does this person have in the country of Australia? They don’t live here, they don’t vote here etc.

There’s a tax deduction for corporate donations. Why would you want to subsidise corporations to participate financially in your elections? They’ve got enough money. If they want to participate they are going to do that anyway so why give them a subsidy to do so?

Question — Just in relation to the last bit: corporate donations tax deductions are gone. They went in legislation earlier this year. In relation to PACs (political action committees) and third parties in campaigns, one of the key things we’ve had in Australia is ideas like the unions and GetUp! would be very strongly against any limitation on their ability to campaign. That seems strange because in the US it is the right which says we have the right to run PACs and spend as much as we like whereas over here it is the GetUp!s and the unions who say why can’t we have unlimited expenditure in campaigns? What’s your view on that?

Diana Dwyre — Well groups like GetUp! in the United States who are on the left side of the spectrum, they don’t criticise some of these decisions either. They would like to be able to raise and spend unlimited amounts and so it is those groups in general that are interested in not being regulated. That’s not necessarily partisan or ideological.

Question — Isn’t it a consequential amendment that any limitation on expenditure and donations to parties has to be consequential, that there has to be a limitation on third parties or else money will simply flow through. I won’t give money to the Liberal Party I’ll give a million dollars to Citizens for Lower Taxes who then run negative campaigns against the Labor Party so that the net effect is that my money is going towards arguably a stronger more negative campaign. It is a consequential thing, surely, that third parties have to be capped.

Diana Dwyre — I think that that is where societies really have to look at what kind of elections you want. Do you want elections that come from parties and their candidates or do you want elections where these third party groups, interest groups really are speaking the loudest? And so by regulating in particular ways you can create certain consequences. So if you don’t want to allow third party groups to overpower the voices of candidates and their parties then you have to limit both sides. That’s why limitations can work in that way. In Australia I’m not so sure that your courts would decide in the same way that ours have recently and say that such limits are unconstitutional. I don’t think they will. Most of the scholars who’ve commented on pending legislation have said no, that’s not the same kind of limitation that we see happening in the United States. But you are absolutely right. That’s where you have to step back and say what’s important to us? What kind of elections do we want to have? And you are also right to point out that those elections run by third party groups who have nothing to lose and aren’t on the ballot tend to be more negative. So you’ll get that as a consequence if that’s the kind of system that you create.

Question — In terms of the American system where you’ve got contributions going to the candidates from individuals and PACs that are limited and then you’ve got the independent expenditure that’s essentially uncapped, how is the difference between those things defined? If a candidate was to collude with an independent group to organise, how does that work itself out?

Diana Dwyre — You are not allowed to. It won’t be independent. The rule is that if you want to spend in an unlimited fashion independently it has to be independent. You are not allowed to talk with the candidate or communicate with them or anyone from their staff in any way. And both sides kind of keep an eye on things and make sure that is not happening. There have been lots of accusations from one candidate about the other candidates: ‘Oh, you must have talked to this group, they are saying the same thing you are’. ‘Well’, the other candidate will say, ‘they just saw my ad on TV and they are saying the same thing’. The penalties again for that kind of collusion are very high. It is probably not worth it. The political parties who can spend independently as well: if you go into the Republican National Committee headquarters you will see that there is a different floor of the office building that’s dedicated only to independent spending. They don’t talk to the staff people who do the contributions and the other strategy. So they even keep that separate within a party office. Just to make sure they are not breaking the law.

Question — As a dual American–Australian citizen I really appreciated listening to your talk with both halves of my brain. With the American half of my brain, I’m really curious about when freedom of speech, freedom of expression got equated with money. I’m also curious about the First Amendment which in my understanding applies to the individual, how that got extended to the corporation?

Diana Dwyre — By the courts in 1976 in Buckley v. Valeo. That’s the first time we see the courts applying very directly this idea of the First Amendment freedom of expression to money and politics. It’s not the very first time we’ve seen the Constitution or the Bill of Rights applied to corporations. Back in the 1920s corporations were given the right of corporate ‘personhood’ under the Fourteenth Amendment which is the due process clause which allows one to be treated fairly under the law. That is really a two-sided thing so corporations could then defend themselves in court but also be able to act as individuals so that if I accuse a corporation of harming me in their workplace or something they would be able to defend themselves at court. They have due process rights. Also it allows me, because there is someone to sue. A corporation has due process rights and so do I. Before that time a corporation could say well there is nobody here to blame. That’s just how things are. And there is no law saying we can’t have child labour or unsafe working places or whatever. So until the 1920s that was something that corporations could get away with. So it was important to establish that. But it wasn’t until 1976 that it was applied to money and politics.

One of the criticisms of this recent Citizens United case is that what it’s done is to create eligibility for corporations to have First Amendment rights and this is the point at which that happened. Before this time corporations did not have any First Amendment rights really, the only place in the Constitution and the Bill of Rights where corporations have any protections is the Fourteenth Amendment, the due process clause of the Constitution, and that has been utilised many times over. So this is new territory. A lot of legal scholars are suggesting it could have a lot of different kinds of consequences, things like corporate liability for fraud, the kinds of advertising they are permitted to do, all kinds of areas where this might encourage corporations to push the envelope. We don’t know how they might interpret it, what they might do with it, but that is what people are talking about.

[1] Source: Federal Election Commission, ‘2008 Presidential Campaign Financial Activity Summarized: Receipts Nearly Double 2004 Total’, News release, 8 June 2009.

Prev | Contents | Next

Back to top