Papers on Parliament No. 44

January 2006

A.J. Brown "The Constitution We Were Meant To Have*"

Prev | Contents | Next

Re-examining the origins and strength of Australia’s unitary political traditions

Australians do not need state governments. In fact, we never needed state governments. If the French explorer La Perouse had arrived in Australia before Captain James Cook, we would not have had states at all. So for all those absolutists who think that states are essential to our future, I say that we only have them because of the fate of a breeze.[1]

More than a century after Federation, and 150 years since responsible government, Australians can be trusted to be positive about the fact they are a relatively liberal democracy. They can also be trusted to be satisfied that they are a nation, and probably that their national constitution is one which recognises more than simply one national level of government—that is, that their constitutional system assigns importance and permanence to what law-and-geography scholars call sub-national as well as national ‘legal life’.[2]

Beyond these presumptions, however, it becomes difficult for political scientists to claim consensus about social satisfaction with the form of the Australian federation, or the specific political geography of Australian federal, state and local government. Instead Australians, commentators and political leaders alike, tend to adopt a certain fatalism or impotence regarding a political structure that we often admit to be inadequate, but with which we must resign ourselves to work because history has taken the matter out of our hands. Popular stereotypes abound regarding the unfortunate if not incompetent way in which colonial Australia was subdivided by British authorities between 1788 and the granting of responsible government in the 1850s, leaving us with a lop-sided group of colonies and subsequently a lop-sided federation. By 1901, ‘the political history and geography’ of these established self-governing colonies made it ‘hardly surprising’ that Australia became a federation,[3] but its specific structure is not something of which many seem proud. In 2002, Prime Minister John Howard told Australia’s National Assembly of Local Governments that he was in no doubt that ‘if Australia was starting over it would not have the same government structure’, even if he also concludes that to worry about it now is ‘an empty theoretical exercise’[4] or ‘pure theorising’.[5]

Are we accurate in our assumptions about the twists of constitutional history that we now see as regrettable, or the notion that it is pointless to ponder on how things might be made better? This paper continues an argument begun earlier[6] that it is in fact vital to ponder these assumptions, because in many serious respects, our diagnosis of our own history has become quite inaccurate. For example, we now know to question assumptions that Australia’s rough-and-ready colonial subdivisions were forced on British colonial authorities by dint of circumstance, reflected poor or non-existent European knowledge of the ground, and only later came to be part of an ex-post-facto federal idea. Instead we have evidence that British authorities probably launched the subdivision process, in the 1820s, with an ultimately federal dependent nation in mind. On this account, when joined by the evidence of colonial communities campaigning actively for colonial separations, and also still thinking nationalistically from an early stage, we develop a picture of earlier, but different styles of federalism embedded in our imported political culture than we often let on. Rather than Australian federalism developing later, in the late nineteenth century, we are now beginning to see that federalism arrived in the 1820s–1830s; and that far from creating a superficially perfect and natural federal union in the 1890s, our subsequent constitution-making only succeeded in institutionalising the less dynamic and democratic of these underlying federal values.

Similarly, a deeper grasp of the history and unresolved conflicts between Australian federal ideas is only part of the key to understanding our ongoing constitutional dilemmas. Another body of ideas is clearly relevant: the theory that Australia would always have been better served by a unitary political system. In such a system, sovereignty is not divided between the national and state governments in the manner of a federal system. Instead, as in British traditions, the sovereign legislative power of the people would be vested in the national parliament without formal restriction; and in place of the states, alternative sub-national governments would exist at the provincial and/or regional and/or local level, of obvious great practical and political importance in the constitutional system but not claiming their own ‘sovereignty’ in a federal constitutional sense.

The earlier paper mounted a claim that to understand the structural and territorial dissatisfactions affecting Australia’s constitutional system, we should place our history of these unitary traditions alongside those of our federal traditions, and can in this way discern a ‘territorial trio’ of traditions including a better view of the ideas—and problems—that dominate today.[7] (see Figure 1 below). This paper seeks to explain the history and importance of these unitary traditions in Australian constitutional debate and practice—not as an exhaustive guide, but as a demonstration that as with alternative bodies of federal ideas, the influence of unitary ideas is far more real, pervasive and abiding than recent political science or constitutional theory has often been prepared to admit.

The first part of the paper investigates the nature of the predominant unitary theories by tracking some of their major manifestations in Australian political debate. This background reveals unitary theories to be not the kind of marginal cross-current of political ideas that some defenders of federalism sometimes allege, but rather a deep undercurrent of our political practice of federalism that appears unlikely to ever go away. This historical review also provokes some basic questions similar to those posited earlier in relation to our federal theory: when did coherent notions of a national unitary political structure for Australia commence, and where should these stand in contemporary understandings about our original destiny? The second part of the paper answers these questions by locating ‘the constitution we were meant to have’: the Stephen model, a constitutional structure that British colonial authorities sought repeatedly to introduce to Australia over the decade from the late 1830s to late 1840s, before giving up and largely washing their hands of Australian constitutional affairs. This original unitary blueprint remains important today, not simply as an under-recognised historical event but because it resonates strongly with so many subsequent alternative theories, and correlates with what many may argue is a continuing trajectory of constitutional evolution. In conclusion, I argue that by better understanding our own history of ideas, we may have some better prospect of discerning the best of these traditions and giving them greater force in our constitutional development. The alternative seems to be a continuing, unrewarding, inefficient and potentially fruitless struggle to reconcile ourselves to a constitutional system that combines the worst, rather than the best, of our major traditions.

|

|

First Federalism (Decentralist)

|

Unitary Traditions (Decentralist)

|

‘Conventional’ Centralised Federalism

|

|

Period

|

From 1820s

|

From 1830s

|

From 1840s

|

|

Source and route of ideas

|

American federal experience, directly and via British colonial policy.

|

‘Pure’ British unification theory boosted by Canadian experience.

|

American federal, British unification and Canadian ‘consolidation’, via British colonial policy.

|

|

Politics

|

British progressive.

|

British universal.

|

British conservative.

|

|

Commencement locations

|

Hobart, Melbourne.

|

Adelaide, Melbourne? Sydney.

|

Sydney.

|

|

Mobilisational orientation

(King 1982)

|

Major decentralization followed by partial centralization.

|

Decentralisation within centralised structure.

|

Partial centralisation.

|

|

Key manifestations

|

Colonial separation and new state movements; 20thCentury Federal Reconstruction Movements.

|

Strong local government systems as alternative to territorial fragmentation; movements for state abolition.

|

Australian federation/unification movements generally.

|

|

Present at Federation?

|

Yes.

|

Yes (Unification).

|

Yes (Simple compact).

|

|

Balance achieved?

|

Arguably not yet (no substantial territorial decentralization since 1859).

|

No (credible local/ regional governments never allowed to develop).

|

Arguably not yet (decentralization demands remain unsatisfied by centralised surrogates).

|

Unitary theory in Australian politics

In recent decades, arguments for a unitary political system—often framed in terms of the abolition of state governments—have been distinctly out of vogue among dominant political groups, scholars and commentators. The last strong defence of the unitary alternative by a political scientist[8] came at an inopportune time. A majority of politics scholars instead became interested in the apparent revival of federalism, and an apparent consensus that federalism as we know it is now permanent, even if problematic—the challenges are to learn to finally make it work properly, after 100 years, rather than to keep whinging about its inherent conflicts and dysfunctions. As often happens, the Australian revival followed a similar one in North America and Europe, where federalism had previously been depicted as a transitory stage in the evolution of nations, destined either to disintegrate or mature into more integrated, unitary forms of government as ‘primordial’ territorial cleavages like ex-colonial states naturally faded away.[9] However by the 1970s we began rejecting this modernist vision and decided that such cleavages were destined to remain. If by nothing else, federalism's permanence was made explicable by the fact that territorially, it has its own powerful ‘self-perpetuating dynamic’.[10]

This acceptance of federalism—or at least, this degree of acceptance of one interpretation of federalism—has nevertheless come at a cost. We seem at a loss to explain why a diversity of voices continue to proclaim the need for substantial structural and territorial reform of the Constitution, and in particular why such reform could validly be based around abolition of the States. Apparently satisfied that our current federal framework is the 'highest' constitutional form to which we need aspire, Professor Brian Galligan[11] had little time for the suggested revival of the unitary idea by former Fraser Minister, Ian Macphee;[12] nor for suggestions by the Business Council of Australia that Australia should ultimately aim to restructure its constitution—whether federal or otherwise—from three tiers of government to something closer to two.[13] Other popular expressions of such views, such as Rodney Hall’s book Abolish the States! (1998) pass completely under the radar of serious analysis. Yet there seems to be at least as much permanence to this under-current of opinion as to current ideas of federalism. What’s more, the idea of major constitutional restructure around unitary principles is not simply an elite or expert phenomena, but seems deeply ingrained in popular attitudes. Galligan accepts that ‘so long as Australia has a federal system there will probably be critics calling for its abolition’,[14] while Glyn Davis[15] has described calls for abolition of one tier of government as not just strong but ‘likely to get stronger.’ The Constitutional Centenary Foundation found considerable evidence that serious reform remained an issue, particularly among young people and local government; while empirical evidence in 2001 pointed to belief by a majority of Queensland adults that the constitutional structure should and probably would change in a major way.[16] In practice, particularly with the federal government and all State governments being of different party-political persuasions, much public debate continues to be conducted with a reliable degree of hyper-criticism of the value, behaviour and relevance of the states.

What are the origins of these broad veins of constitutional dissatisfaction? In addition to dissent based on Australia’s original decentralist federal traditions, do these apparently anti-federal ideas rely on a preferred unitary theory, and if so, what do they contain and when did they commence? As with federal ideas, the need for a complete history is growing. At the close of the 20th century, one sympathiser seemed to believe that popular ideas of state abolition were relatively recent, almost embryonic.[17] Another frequent assumption is that debate ‘for and against the states’ has only been occurring ‘on and off’ since Federation,[18] as if unitary ideas have had their main life as a reaction to federalism, only relevant since Federation itself.[19] Yet another frequent assumption is that unitary ideas as opposed to federal ones, or ‘Unification’ as an alternative to ‘Federation’, are based in an inherently centralist, socialist model of government, the Australian Labor Party having adopted this as a constitutional platform from 1919 to the 1930s, and kept it on the books until the 1960s, with resonances into the 1980s and 1990s.[20]

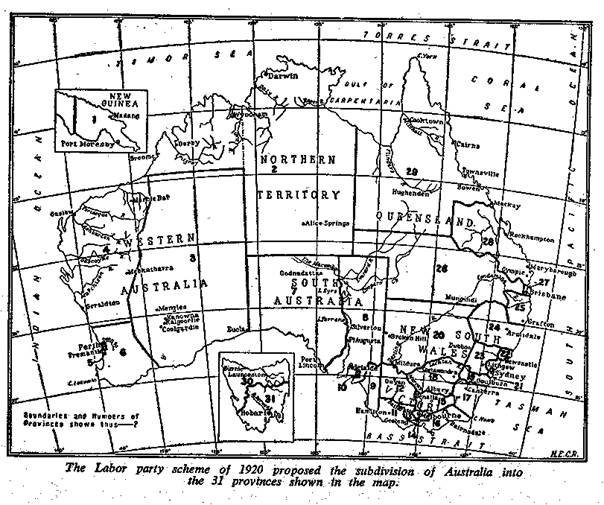

There are clear reasons to question all these assumptions, and look for some of the more abiding characteristics of unitary theory over time. Certainly, Labor’s attacks on the states elevated anti-federalism to the highest levels of political debate, not least in the Unification platform, symbolised by the map at Figure 2.

Figure 2. Labor Party map 1920

Source: U.R. Ellis, New Australian States. Sydney, Endeavour Press, 1933.

However, it is vital to note that Labor was not the sole force of twentieth century centralism, and in the early twentieth century, certainly not the sole force nor the originator of unitary constitutional plans. The clearest counterpoint is that Labor was almost beaten to its unitary platform by the founder of the Country Party, and lead ‘new state’ activist, Earl Page.[21] Page’s 1917 ‘plea for unification’ denounced Australia's ‘bastard constitution’ even before this became fashionable in the Labor Party.[22] Signficantly, Page’s assault was not leftist and clearly sought at least as much decentralisation as centralisation, in the form of new ‘provinces … big enough to attack national schemes in a large way, but small enough for every legislator to be thoroughly conversant with every portion of the area.’

In order to understand why such sentiments existed, and how deeply they ran through Australia’s political and constitutional fabric, we would need to review the entire state of federalism’s development and dysfunctions at the time. More simply, for present purposes, we can also measure the relative strength of these ideas through some of the major reactions to those dysfunctions. A first example is the 1927–29 Peden Royal Commission on the Constitution, appointed by the Bruce–Page Commonwealth Government as the first major general evaluation of the systems of government established at and since Federation. Of the seven members, five (Peden, Colebatch, Bowden, Abbott and McNamara) were federal and state parliamentarians chosen to represent the party interests of the time, with additional representatives from the union movement (Duffy) and employers (Ashworth). The wider strength of the idea that Federation should evolve into Unification was demonstrated by the minority report to this effect by three of the seven Royal Commissioners (McNamara, Duffy and Ashworth), criticising the state divisions as ‘not planned in accordance with any principle’; ‘mere historic accidents’ that ‘are not natural’.[23] Particularly telling was the fact that Ashworth, invited onto the Commission as the Government’s representative capitalist, opposed the Government’s own representatives and sided with labour on this fundamental issue.

A second example of the strength of unitary values, from the same period, is the famous turn taken by the High Court of Australia in 1920 in its approach to interpretation of the Constitution’s attempted division of legislative power between Commonwealth and states. In the Engineers’ case (1920), a court dominated by its second round of appointees, Henry Bournes Higgins and Isaac Isaacs, overturned the various attempts by the original Griffith court to quarantine state legislative power from erosion by the Commonwealth through the doctrine of state ‘reserve powers’. Higgins and Isaacs had, of course, been part of the substantial minority of 1890s Federation delegates who consistently pushed for larger federal powers than ultimately agreed in the 1901 constitutional text. However just as important as the fact they finally had their way in 1920, is the extent to which their reasoning was explicitly opposed to federalist principles of divided sovereignty, and based instead in British-styled unitary constitutional values, as demonstrated by the lead judgment delivered by Isaacs:

The Constitution … recited the agreement of the people of the various colonies, as they then were, ‘to unite in one indissoluble Federal Commonwealth under the Crown of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland …’. ‘The Crown,’ as that recital recognises, is one and indivisible throughout the Empire. Elementary as that statement appears, it is essential to recall it, because its truth and its force have been overlooked, not merely during the argument of this case, but also on previous occasions. Distinctions have been relied on between the ‘Imperial King,’ the ‘Commonwealth King’ and the ‘State King’. … The first step in the examination of the Constitution is to emphasise the primary legal axiom that the Crown is ubiquitous and indivisible in the King's dominions. Though the Crown is one and indivisible throughout the Empire, its legislative, executive and judicial power is exercisable by different agents in different localities …. . [But nevertheless] The Commonwealth Constitution as it exists for the time being, dealing expressly with sovereign functions of the Crown in its relation to Commonwealth and to States, necessarily so far binds the Crown, and laws validly made by authority of the Constitution, bind, so far as they purport to do so, the people of every State considered as individuals or as political organisms called States.[24]

While perhaps inevitable as an interpretive approach, the direction taken by the High Court since 1920 has often been credited with assisting a trend of centralization in the federal system, given that from this time the Commonwealth tier of government could be validly characterised as a unitary system in its own right, overlaid on the existing unitary systems of the states, whose legislative powers were truly unlimited provided they held to their enumerated subject matter (all capable of broad definition). From the 1940s, this interpretive method combined with expansive use of the defence and taxation powers, enabled the Commonwealth to begin dominating the federal system in ways that certainly cured many of the uncertainties of the early post-Federation period, and which many regarded as necessary if not vital if Australia was to build the type of integrated, national industrial-era economy desired in the 1950s–1960s. The ascendancy of unitary values in this process is well recognised, even if also lamented by many, as captured in 1954 by the economist S.J. Butlin:

[I]n most, but not quite all, functions of government we have an effective unification within a nominal federalism … . To deplore the departures from what the Founding Fathers designed is perfectly legitimate; to see dangers of centralisation and overgovernment in trends away from … federalism may be completely justified. But it is not sensible to believe that it is practical politics to secure in this country a reversion towards federalism and less of the near unitary state we have reached. The clock will not go backwards.[25]

The clock has certainly not gone backwards since 1954. Australia’s species of ‘federalism via double unitary centralism’ has led to a uniquely centralised form of constitutional system, especially in its structure of public finance. In 1999 the introduction of a New Tax System was rationalised and defended on the basis it would deliver all the proceeds of the federally-collected Goods & Services Tax (GST) to the states. However this only extended the previous ‘vertical fiscal imbalance’, as noted by Canadian political economist Stanley L. Winer’s query about fiscal centralization being ‘so pronounced in Australia that one is tempted to ask if an initial constitutional division of powers imposes any constraints at all on the actual effective assignment of policy instruments.’[26] In March–April 2005, the eventual realisation that state governments have no more enforceable constitutional right to the proceeds of the GST than to any other federally-collected taxes, has borne out the lone voices who earlier identified the GST as a ‘stealth missile’ for the states.[27] Constant arguments for the inherent virtues of uniform legislation in almost every area of public policy, and the need for this to be pursued by cooperative negotiation in the few areas where the Commonwealth cannot already achieve it by legislative or financial force, emphasise the extent to which Australia has, in many respects, a unitary system.

To fully understand these unitary trends, we still need to know where they came from. Clearly their ascendancy is not owed mainly, or particularly, to any subterranean victory of socialism through Labor’s ‘Unification’ policy – many of the most important and longest periods of Commonwealth centralization and consolidation have been under supposedly ‘federalism-friendly’ Conservative governments. Nor does it any longer seem plausible that Labor’s endorsement of Unification resulted primarily from its role as the major political group ‘not a party to the original constitutional compact’ of the 1890s, as widely believed even by Labor historians.

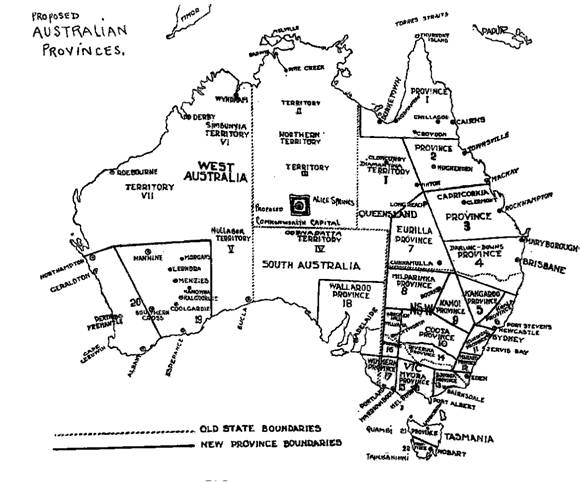

Figure 3. Provinces and territories of a unitary Australia

J.B. Steel, 1908–1913

Source: John Boyd Steel in Albert Church, Australian Unity, Sydney, Australian Paper Co., [1913], p. 191.

At least three further bodies of historical evidence point to the entrenched nature of unitary values as a feature of the Australian popular-political psyche, well ahead of the events of the 1920s. The first is the evidence that neither Page nor Labor invented these alternative constitutional ideas, any more than federalist ‘new state’ ideas were invented at this time—rather they adopted them out of an existing populist debate in which the reputed qualities of 'unification' transcended the early left-right divide in national politics. The first 'homegrown' map of an alternative, post-colonial territorial structure under a unitary Australian constitution apparently surfaced in 1913, drawn by an eclectic group of utopian Victorian-era nationalists led by John Boyd Steel (Figure 3).[28]

A second critical body of evidence comes from the fact that ideas about Unification did not simply postdate Federation, and all its early teething problems, but had circulated as a discrete alternative to Federation since before the latter occurred. Prominent examples include the 1894 plan of NSW premier George Dibbs,[29] while as early as 1879, Henry Parkes had also assumed that British unity was the right template for union, with separate jurisdictions amalgamated under one legislature.[30] Even if Dibbs' or Parkes' original ideas are dismissed as maverick or driven by short-term expedients, they clearly are not explained by socialism, Labor’s role in Federation, nor any twentieth century economics and party-politics.

Nor is it necessarily safe to assume that these unitary theories were marginal to the theory or politics of Federation as it was ultimately achieved. A third body of evidence indicates that to a significant extent, the concept of Unification—entry into nationhood in the form of a unitary political system, with a national parliament to act in place of the Imperial one—underpinned and energised the concept of Federation itself. In many ways this is not surprising, since we know that popular political demand for unity must have been strong to force such independent colonial legislatures to surrender any of the autonomy that clearly had to be sacrificed in any union. However the key to understanding just how strongly the popular sentiment ran, seems to lie in the extent to which Australians and their leaders liked to liken the value of territorial union not simply to American precedent, but more directly to the notion of territorial union embedded in their vision of the United Kingdom. Britannia ruled because it had managed to consolidate itself into one nation out of four: England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales. And of course, Britain had done so not via a federal union, but a legislative unification in which just one parliament reigned supreme, representing all within a singular sovereignty so glorious in its conceptual ubiquity and indivisibility, as well as its geopolitical power and economic success.

According to Christie, the concepts of political unity that flowed from this vision of the Mother Country were positively reified in British colonies in the late nineteenth century.[31] In Australia, where the superiority of British political precedent was rarely subject to question,[32] we see this reification in the convictions regarding the cultural, religious, racial and political homogeneity of the colonies, that so explicitly underpinned arguments for union. We also see it in the language of British-style ‘Unification’ used by a range of leading unionists. For example, Western Australia's John Forrest argued Australia met the conditions for British-style unity so well there was simply no further need for ‘imaginary lines drawn on a map, which in a great many instances are drawn haphazard’.[33] After editing the first official draft Constitution, Queensland premier Samuel Griffith publicly described the goal of this union as ‘unification’, a means of overcoming colonial divisions that were mostly ‘imaginary lines’. For all his admiration of America, Tasmania’s Andrew Inglis Clark, of loyalist Scottish descent, took as his primary territorial reference the ‘entire and perfect Union’ created when Scotland and England joined in 1707.[34] Popular cartoons depicted the ‘happy federal family’ not preserving but ‘clearing away’ colonial boundaries.[35] This public political logic, as opposed to that with which the constitutional text was negotiated, discloses some of the distinctly unitary underpinnings of Australia's national rationale. Another example, from four decades earlier at the time of responsible government, comes in the form of the Shoalhaven petition of 1853, calling for a national union in Australia on the basis that the ‘great study and aim of all practical British Statesmen’ had always been ‘not only to have and preserve one British Constitution, but also to assimilate the local laws of England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales …’.[36]

Finally, in tracking Australians’ unitary predilections back to this somewhat sentimental, colonial-era ideal of British national unity, we find a further key feature common across our experience of unitary traditions. This is the extent to which models of Unification have been based not simply on the presumed benefits of national unity, but on decentralised unitary principles in which—notwithstanding the undivided sovereignty of the national parliament—much of the real work of government needed to be carried out by sub-national political authorities of various kinds. Such was the true nature, of course, of British rule in which local and county government had always still been taken for granted. In Australia’s case, in fact, unification proposals such as Dibbs’ 1894 plan, the Steel-era plans, and even the ALP 1919 plan presumed a written constitution in which the legislative power of the national parliament was indeed comprehensive, but in which the territories and powers of the sub-national units (typically provinces) were nevertheless still also constitutionally protected. The mysterious way in which Earl Page held to both unification and new states as a goal, therefore, also becomes less cryptic as we appreciate this intersection of principles. Just as Federation had unitary underpinnings, so too Australian ideas of Unification had already internalised many fundamentally federal principles.

Figure 4. Regional states of a Renewed Commonwealth—

Chris Hurford (1998, 2004)

Source: C. Hurford, ‘States, regions and citizenship: constitutional changes we need to make.’ Weaving the Social Fabric Public Lecture Series, University of South Australia, 1998; and ‘A republican federation of regions: reforming a wastefully governed Australia’, in Hudson & Brown, Restructuring Australia op. cit.

If we leap back to the present day, we find further evidence of this overlapping in one of the more recent constitutional alternatives to emerge, advanced by former Labor Minister Chris Hurford (figure 4). Hurford’s plan resonates strongly with unitary traditions, not least in its proposals for a similarly decentralised political structure. However this unitary-style plan is also presented explicitly as an endorsement of, and not derogation from, the principles of federalism, possibly for the first time ever in Australian public debate, and certainly since that crucial period in the 1920s when our present federal and unitary stereotypes began to ossify. One of the most visible and crucial features of our unitary traditions, therefore, is that they have sought to institutionalise both national and sub-national ‘legal life’, but to formally enlarge the former and to reconstitute the latter at a spatial level closer to that which we would today regard as ‘the regional’. This is also the essence of federal theory as endorsed by Australian scholars, even if not Australian federal practice.

Do we have a constitutional tradition, then, in which we have sometimes combined the best of both these original veins of constitutional thought: our original decentralist experiences of federalism, and our British-style unitary values? If so, we might also ask how this potential for overlap compares to the type of reconciliation we have achieved in practice in the present day. But before concluding with these questions, we have two further historical mysteries to resolve. When was the idea of a unitary constitutional structure first mooted as a coherent option for Australia as a continental entity? And in particular, if some Australian colonists quickly came to see the logic of a national constitutional structure using these principles, how confident are we that British colonial authorities didn’t also do so?

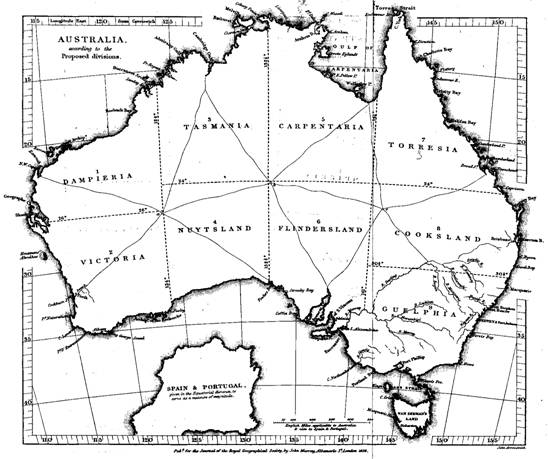

Figure 5. Vetch’s Map

Source: James Vetch (Captain), ‘Considerations on the political geography and geographical nomenclature of Australia’, Royal Geographical Society Journal, vol. 8 1838: 157–169. My thanks to David Taylor and Nigel Rockliffe for drawing this map to my attention.

‘The Constitution We Were Meant to Have’: British unification policy 1830s–1840s

As indicated in earlier parts of this paper, Australians have often rooted the perceived dysfunctions of their federal system home to the British decisions resulting in a curious tapestry of colonial boundaries by the time of the Australian Colonies Act 1861. According to myth, the lop-sided nature of Australia’s constitutional system can be blamed on the ‘blind Whitehall clerk’ supposedly responsible for these misinformed subdivisions.[37] Such myths remain pervasive even among recognised political conservatives, despite also carrying the double-edged sword of a sense of destiny having passed out of our control—such as when Minister Tony Abbott reflects that it is ‘important not to be sentimental about the States’, ‘accident as much as design’ having made Australia a federation.[38] Yet we know the history has not been a matter of blind fate. Some of the most important divisions were fought out primarily in colonial political debate rather that originating in London. On a broader level, we also now know that official British thinking about the territorial dimensions of Australian constitutional development was not blind, but more comprehensive and oriented towards an eventual, inevitable nationhood. Figure 5 above provides a useful reminder of the reality that national blueprints were part of British thinking from an early stage.

We also know that British colonial authorities did not begin with a preference for a unitary (and centralised) political approach, only to be forced by local realities to grant the subdivisions that resulted in a federal system. Yet the fact remains that the process of federal-style subdivision that commenced in 1825 rapidly faltered. Three subdivisions occurred between 1825 and 1836, but the subdivision of Victoria was held up until 1851, and Queensland did not follow until 1859 – putting aside all the other demanded or possible subdivisions that never followed at all. This slowing and uncertainty all suggests a certain confusion, lack of interest or possible incompetence. Was colonial politics itself the only problem, in the form of resistance from local Sydney officialdom and the pastoralists dominating the fledgling New South Wales Legislative Council?

The answer to both the above questions—why the British plan of federalist subdivision faltered, and when did the first coherent plan for a unitary Australia appear—is the same. From the late 1830s, in a reverse trend to that commonly assumed, the experiences of the British colonial office led it to move away from federal-style subdivision as its first preference in constitutional design, back towards unitary theory. In this period the British colonial office developed the first coherent plan for an Australia with a constitution based on unitary principles. This ‘constitution we were meant to have’ was a decentralised unitary political structure capped off by a general (national) parliament but in which the bulk of government was effectively carried out by district (regional) councils. The new theory argued that while existing colonial groups should still be welded together into national dominions, colonisation and decentralisation need not be reliant directly on territorial subdivision, but rather pursued by devolving responsibility onto 'district councils' free of legislative trappings. On this plan, colonisation could be supported more flexibly and efficiently, while promoting a national legislative jurisdiction with an appropriate sense of unity, and allowing government to develop along something closer to a traditional British unitary lines. This plan was highly developed, pursued over a 10 year period through three phases of policy proposals. Only after these attempts were exhausted, in 1847, did the colonial office reluctantly re-endorse subdivision as a constitutional strategy, freeing the way for separation of Port Phillip.

The first step in understanding the rationale for this policy shift, and one of the reasons why it has gone under-detected in Australian history, is that it was galvanised not by events in Australia but in British North America. Whereas the 1820s saw considerable official interest in the colonial benefits of American federalism, by the late 1830s the problems of imitating a multi-colonial strategy in Canada were causing a major change of heart. As a single province, Canada was separated into two in 1791, but almost ever since, French-speaking Lower Canada had been a political problem. In 1836, the Gosford Commission was appointed to devise a new constitutional formula, but its mixed results were rendered out of date when armed revolts in Lower Canada in 1837–38 prompted a more decisive British reaction—the total reunification of the Canadas with a single colonial legislature, under the Union Act of 1840.[39] The Canada problem cemented the British consensus that it had been a mistake to separate the Canadas in the first place. Particularly when the problem was a territorially-discrete cultural minority, the experience provided a direct reminder that Britain's own constitution contained a territorial strategy for welding disparate populations into one powerful nation—the type of unitary legislature in which minorities could be represented but still contained by the national interest, the principle ‘found perfectly efficacious in Great Britain’.[40]

In Australia, the resolution of the Canada problem was read not for its territorial implications, but for the principles of colonial responsible government set out in Durham’s report. [41] In reality Durham’s argument that a unified legislature was competent to exercise far greater power was part of the argument for territorial reunion, not necessarily a goal in itself.[42] Less directly relevant, and thus apparently less obvious to Australia’s colonial leaders was the underlying shift in sympathy away from the idea of multiple colonies. Decentralisation remained an intrinsic goal of colonial development and the federal territorial path remained one alternative, but it was no longer preferred.

The alternative Australian plan, on more unitary principles, had already been evolving since 1836 in the mind of James Stephen, permanent under-secretary of the Colonial Office. The first of Stephen’s three attempts to introduce his model began in 1838, and like the subsequent two attempts, it is most obviously tracked in the evidence of British attempts to introduce the cornerstone of any decentralised unitary system: a comprehensive system of local government. This was missing in all four Australian colonies, and was a cause of great consternation, partly because it provided no institutional platform for local development and partly because New South Wales’ largely ex-convict free population was still considered politically immature to elect a full legislature. In response, Stephen negotiated a Constitution Bill for New South Wales which included a more powerful and representative legislature, but whose members were to be secondarily elected from a new, first tier of local councils. While this Bill languished pending the decision on convict transportation,[43] the Colonial Office nevertheless began proceeding down this path in Western Australia, where Australia's first town trusts and councils were formed in 1838, and in Adelaide where, unlike in Sydney, a town council was incorporated a year later.

In the first phase, Stephen’s strategy had mixed success. The Western Australians were struggling to survive and could barely support even the first local tier of government. The South Australians successfully established the first tier, but financial difficulties suspended debate about the second.[44] The NSW Bill remained in limbo, but in May 1840 the NSW Governor Sir George Gipps introduced a local government Bill into the still-appointed NSW legislature, then withdrew it amid conflict between those of non-convict and ex-convict background.[45] This led to Stephen's second and most major attempt. In the NSW Constitution Act 1842, the British parliament finally enacted a new constitution for a two-thirds elected Legislative Council, as is well known, but also a detailed system of District Councils as the new base unit of territorial organisation in the colonies. A multitude of council charters were issued and the system quickly showed signs of working at Port Phillip, but in the Sydney districts the attempt failed. By late 1845, all but one council was financially defunct, the new Legislative Council having used its power to deactivate the rating power on which the districts depended. The NSW legislators’ mantra of ‘no taxation without representation’ now meant ‘no taxation without responsible government’, coupled with the obviously self-interested reasons why the major pastoralists opposed making any such payments.[46]

Not yet admitting defeat, the Colonial Office concluded in January 1846 that the mistake had been to break the legislature's electoral dependency on the ‘municipal institutions designed to keep it in check’.[47] Sir George Gipps replied that there was now no alternative to separating the Port Phillip district as its own colony, even though this would offend the new policy of avoiding ‘dismemberment of any colony which, like New South Wales, may be of a size hereafter to become a nation.’[48] Nevertheless, Stephen tried one more time. The third and final attempt saw Stephen revert to the 1838 plan and seek a secondary election nexus so that the existing legislatures became chosen by the District Councils. The 'Australian Charter' containing these principles was dispatched to the colonies by the secretary-of-state, Earl Grey, in July 1847, combining Stephen's scheme with Grey's new plans for a free-trade national union, and reclassifying each of the existing four colonies as 'provinces' whose secondarily-elected legislatures would then choose further delegates to a national assembly.[49] The end came when Grey abandoned the attempt in early 1848, after the Governor of New Zealand rejected an equivalent scheme for his colony sent seven months earlier, quickly followed by renewed Sydney attacks on the District Councils as ‘cumbrous and expensive’.[50] Stephen retired from office, returning just once in 1850 to plead the case for District Councils as a member of the Privy Council Committee on Trade and Plantations, but the attempt was over.[51] In the Australian Constitutions Act No. 2 1850, the British Parliament gave up on the District Council alternative, and instead chose to finally allow the subdivision of NSW to produce Victoria, and the colonies to draft and submit their own separate constitutions.

Even the existence of the Stephen model has been poorly recognised in Australia, let alone its importance and underlying nature. Its various iterations are generally regarded as disparate attempts to introduce some scheme of local government into NSW; only a few even suggest the attempts were connected.[52] The dominant view, stated in Melbourne’s Early Constitutional Development, is that the final Charter reflected Stephen’s ‘ideal system of colonial government’, but that 1847 presented ‘merely the first’ chance for him to pursue it; earlier plans for local government are assessed as an unrelated ‘sop’ (1838) and the product of Gipps’ genuine but ‘academic’ commitment to local institutions (1842).[53] Further, historical scrutiny of the 1847 Charter has been dominated by the assumption it was a ’federal ’ proposal, and therefore not possibly related to any alternative British constitutional theory—an assumption already questioned elsewhere.[54]

Revisiting Stephen’s efforts in context, we find instead a coherent strategy for rebuilding Australian colonial structures on a constitutional path aligned less with federalism, and more with British unitary traditions. Figure 6 below sets out more clearly why this is the case. Although the Stephen model in its final iteration proposed a union of the four colonies, the cornerstone of the plan remained its attempt to reconstitute an alternative, non-federal base unit in the colonial political geography. This had multiple purposes, not least of which was to circumvent the need for more colonial subdivisions; and this fact, combined with the inevitably supreme role of the national or ‘general’ legislature once constituted, would have effectively confined the period of colonial subdivision to a relatively brief phase of Australia’s development (indeed, less than three decades). Consistently with its preferred ‘consolidation’ policies in Canada and elsewhere, the official British intention was clearly to go as far as possible towards reunifying the original NSW into one colony, with one general legislature, while rolling out constituent District Councils as colonization proceeded. Under this model the four provinces (NSW, Van Dieman’s Land, Western Australia and South Australia) may have continued to exist on paper, but would never have developed much functional or political importance in the constitutional structure.

Figure 6. The Stephen Model

The failure of Stephen's model does not detract from its historical significance as the first truly national, but fundamentally unitary and decentralised constitutional plan for colonial Australia. Particularly in their 1842 iteration, the District Councils were destroyed by the resistance of Sydney leaders not because they could not work, as some have since assumed, but because it appeared they would probably work quite well, challenging the power of the existing legislators and fragmenting their demand for responsible government.[55] In principle, Sydney leaders recognised their constitutional legitimacy. James Macarthur, who had supported the original 1838 model, in 1841 gave further assurances that there could be ‘no objection’ to a strong system of local government if ‘placed under the control of … a true legislature in the British sense of the word.’[56] It failed, in essence, because the horse had bolted, in two ways. The British authorities had already let the NSW pastoral elite develop too much power, backed by too much financial support within British politics itself, to institute an alternative political framework. Indeed in fighting to maximise its own position, the Sydney pastoral elite was of course now opposing both types of constitutional decentralisation, whether federal or unitary; but while this fed the Colonial Office’s frustration, there was little ultimately that could be done about it. Similarly direct popular support for the Councils was limited, because communities such as Port Phillip and Moreton Bay—while they adopted the councils—already also had their own concept of greater regional self-government in the form of the colonial separation granted to Van Dieman’s Land and South Australia. In the end, colonial policymakers could move neither forward nor back, and were forced to leave the problems of constitution-making to the colonists of the 1850s and beyond without ever resolving these first half-federal, then half-unitary efforts.

Conclusions: Unitary Theory and Constitutional Debate Today

The rediscovery of Australia’s first truly comprehensive constitutional blueprint, as well as some of the features of our decentralised unitary traditions more broadly, pose both positive and negative lessons for the present day.

The fact that unitary traditions are indeed relevant in the present day is fairly obvious, and not simply in the form of continuing advocacy in favour of constitutional reform or abolition of the states. The legacy of a constitutional system whose base unitary and federal values are inadequately reconciled is with us every day, in a variety of real policy senses: from continuing doubts over the ability of institutional frameworks to transit towards regional environmental and economic sustainability, to arguments over the respective role of federal and state governments in the roll-out of localised services such as health and education, to the renewed imperative for a national and not state-based system of industrial relations, to serious concerns over public infrastructure planning and spending, to pinnacle arguments over collection and distribution of the GST. The question is not whether the Australian federal system is in imminent danger of collapse, as much as whether we might possibly adopt a more informed and intelligent approach to its evolution, in the face of the particular economic, social and environmental challenges that stretch before us in the global era.

A first positive lesson of our earlier unitary traditions, alongside those of our first federal ones, is that whatever their differences, both were distinctive for their strong common focus on how nationalism might be married with decentralization. The problem this highlights is that our dominant understandings of our federal system today contain almost no coherent theory of how public power and resources might be more effectively devolved to the local and regional levels where they are most clearly needed. As reflected at the outset in Figure 1, the third tradition in our ‘territorial trio’, dominating today, is a centralised form of federalism probably unique to Australia, in which two unitary levels of government—state and national—continue to conflict as much as they agree on their respective roles, with at best only occasional indirect political gains at local and regional levels. Even when not keen to ponder this problem too deeply, Prime Minister John Howard recognises and endorses the basic position of those who favour some more lasting, structural solution:

The dispersal of power that a federal system promotes, together with its potential to deliver services closer to peoples’ needs, are threads of our political inheritance that I have always valued and respected. The trouble is that, in practice, there is often less to these arguments than meets the eye. For instance, the view that State governments have benign decentralist tendencies has always been something of a myth … . [57]

In short, despite the richness of our political heritage and diversity of imported and adapted traditions, Australia has not succeeded in capturing the best of each of the two major territorial traditions in our history. While federal and unitary traditions do inevitably now coexist in our constitutional structures in a variety of ways, such as the ‘dual constitutional culture’ built into the design of parliamentary and executive institutions,[58] it is another thing to regard these as fully reconciled in a particularly intelligent or satisfactory fashion. Rather we are confronted with the evidence that in territorial or spatial terms, our mixture of constitutional design and adaptation has mainly succeeded in institutionalizing the worst of each vein of thought. Federalism has given us divided sovereignty, but locked in a spatial strategy in which this has limited practical benefits. Unitary traditions have given us nationhood and a platform for strong government in the Diceyan parliamentary tradition, but the decentralised elements of our unitary traditions have been marginalised and forgotten. No wonder our popular political psyche continues to hold such apparently enduring potential for contemplating the benefits of significant change.

Is change in the wind? Again, the signs are both positive and negative. One of the most promising indications of a revival of decentralised unitary values lies in the next likely phase of developments in Australian local government. Plans to bring local government yet further into the national constitutional system through the mechanisms of public finance, so that all three tiers have an agreed framework by which more federally-collected revenues might be allocated directly to locally-delivered public services, resonate favourably with the Stephen model and the decentralised unitary plans that came thereafter.[59] Similar hope might be held for developments in regional governance more generally, since so many federal and state programs are once again oriented—with the acceptance of each—to policy development and implementation at the regional level. United around ‘triple bottom line’ goals of ecological, economic and social sustainability, the sheer dollar value of such programs calls for a substantial reconsideration of the most capable and legitimate institutional platform for their long-term delivery, if only we can learn the lessons of a history in which the least sustainable aspect of such programs has usually been the programs themselves.[60] Without some serious grappling with the constitutional and legislative basis for overhauled local and regional governance structures, the great and logical fear is that such initiatives will again end up as short-term administrative exercises that wither on the vine, or fall victim to changing party-political agendas, even though we know their philosophy and urgency to be more enduring and long-term.

The final key, then, is political imagination—a willingness to re-interrogate our past for its positive lessons about possible reconciliation of our constitutional traditions, and a preparedness to articulate and pursue a constitutional vision that appeals to values above and beyond those typically targeted in three-year electoral cycles. Even when relatively satisfied with the status quo, many Australians seem capable of imagining yet better ways of governing their nation, and have history on their side when it comes to judgments about this exercise’s importance and validity. What will serve us even better is an enlarged public discourse about how we expect our political systems to need to work and look in another 50 or 100 or 150 years, not because we can know with any precision what will then be needed, but because we know that in any event, our institutions cannot and will not ever stand still. Why admit constitutional defeat, when we have such rich traditions of constitutional debate to inform our collective destiny?

Question — This week Dr John Stone supported the concept of the unitary independence of the states as being the greatest bulwark that we have for the preservation of democracy: opposition to the Federal Government, balanced and continuous. Could you comment?

AJ Brown — I’d like to comment by saying that there is very little evidence that the states have done too much as bastions of democracy for quite a long period of time. In fact, if you look at the evidence as to those things which have acted as brakes on the power of the federal government to act in a unilateral way over the last quarter century, for example, it’s very difficult to find any significant political institution in our system of checks and balances that has had that effect, other than the Australian Senate. There has been a reason for that, which has been that the government of the day hasn’t held a majority in the Senate. Of course that is all about to change for the first time in some time.

When one stands back and looks at the different institutions which are supposed to act as checks and balances of that kind, the High Court because of its history of interpretation hasn’t had that role in terms of many fundamentals, although it has done it a bit in terms of implied rights to freedom of communication and other things that were fairly unexpected. There is very little empirical evidence to suggest that the states really have had that benefit. Most people come back to the fundamental position that they are better than nothing. We wouldn’t want it all in Canberra would we? Even Canberrans wouldn’t want it all in Canberra. The problem is that it is better than nothing; but is that something that we need to settle for? The economic and environmental question is starting to become: is the fact that it is better than nothing something that we can afford to carry on with in this day and age of globalisation and all the pressures that are upon this country? Former Senator John Stone is of course entitled to his views.

Question — At one point in your lecture you mentioned the possibility that there may have been division on the basis of sustainability, and also you mentioned that the lines were relatively arbitrarily drawn in relation to the demarcation of states as they exist at the moment. Had any real consideration been given to the concept of sustainability as a point on which state borders should be drawn? If we look at things as they stand at the moment, there is quite a disparity between the resources which are available. Not only the resources, but the population distribution is perhaps dependent on the availability of resources. Would things have looked substantially different had such an approach been used?

AJ Brown — I think the answer would be yes. It would be completely different. The answer to the first part of your question is that sustainability as such was never a factor in the way in which boundaries played out. There is a very good history that will hopefully be published soon by David Taylor from the NSW Department of Lands on the detailed history of Australian state boundaries, which will be invaluable because every boundary has a different history, especially because they were drawn at different times. In very few cases were they drawn entirely arbitrarily, and that’s a myth that we can well afford to do away with, because it doesn’t help our understanding of how they did come about.

For example, the concept that the Victorian and New South Wales boundary should be on the River Murray, which is something that we now regard as being ridiculous and one of the greatest sources of conflict and environmental problems, was in fact perfectly rational at the time. If you were going to declare a boundary which was partly to delineate where pastoralists should stop, whether they were still in NSW or whether they had passed into Victoria, then what did you use? You weren’t going to be able to get surveyors out there onto the ground to draw a big white line. So for functional economic purposes at the time, you needed to use something which people knew was a boundary when they came to it, and a river was a perfect thing.

Similarly, in the case of other boundaries, the Queensland-NSW boundary was intensely debated over a long period of time and almost everybody had a view and expressed that view, and they were all processed and argy-bargied in the course of figuring out where the boundaries should go. It was by no means arbitrary, and it was largely determined by domestic colonial politics within Australia. The colonial office had very little to do with it.

The question is, if we accept the principle that sustainability should be a factor in the way in which we draw these boundaries, we are basically acknowledging that we’ve got a number of policy frameworks which have administrative needs, and different territorial needs, and how do we draw those? If we drew regional boundaries or provincial boundaries based on the fact that there should be one for every bio-geographic region of Australia, that probably wouldn’t work too well either, because a lot of those bio-geographic regions don’t necessarily have a lot of people in them. We’re drawing lines for people, we’re drawing lines for human communities, as well as for the sustainability of the resources upon which we all depend, and also those on which we don’t depend. So we come back to a fundamentally political question: what recognition of political communities is viable and necessary and in our interests, as much as what framework might serve all these different policy purposes?

We will eventually evolve, and we are already evolving into a new political structure. These things don’t stay static. The same way that the High Court changed its interpretative method and changed the balance of power, things change today. The roll-out of natural resource management agencies under the Natural Heritage Trust Plan; the sort of framework that New South Wales has had for highly autonomous area health boards, whether or not people think they worked, is something which is only likely to happen more nationally. It’s highly likely that eventually Brisbane City Council will end up running hospitals in Queensland. If the Tasmanian government can run hospitals, why can’t the Brisbane City Council run hospitals? Why can’t Newcastle City Council run a hospital? These things are all going to change, and the critical thing will be the point at which we get to a stage where we reach a consensus that the time has come to consolidate our constitution around what is a changed political practice. The question is whether we want to take a really long time to get there, with lots of conflict and blundering around, or to what extent it’s worth saying, let’s do a bit of theorising and let’s have a coherent plan for how this might unfold and see whether we can’t build consensus around that plan, rather than putting ourselves through a very inefficient and expensive process over the next 100 or 200 years.

Question — You mentioned you were going to come back to the question of the difference between regional government under a unitary system and regional government under a federal system. It seems to me that, for example, the Stephen plan was essentially federal, in that the local area was going to be prime and in fact the national government was going to be very much indirectly elected. It’s almost a confederal system as distinct from a unitary system. The question I want to ask is, when you talk about where we might go in the future, which direction are you looking at? Are we talking about a unitary system where sub-national governments are the creatures of the national government and can be abolished and changed, as Kennett did in Victoria with local government, or are we talking about a system where the rights of the lower levels of governments are built into the constitution and therefore always must be taken into account by the national government? That seems to me the crucial difference. We’ve tended in Australia, as you’ve rightly pointed out, to mix up the geographical question with the constitutional structure question, and they are in fact separate questions. A final comment: given that Britain is going away from the unitary system with devolution of Scotland and Wales, how does that affect the British-ness of our system?

AJ Brown — I was talking to a recent British expatriate who has just joined our university and is an expert in this area. He pointed out that what often happens in the colonies is that they take on values that they believe define the culture and the political system of their home country, and preserve them for a lot longer than they are preserved back in the home country. Australians have done this over time in an infinite variety of ways which are quite entertaining, and this is one of them. As you rightly point out, in fact the British passion for unity, the imperative of having a sovereign parliament where the English needed to be able to maintain control over the Scottish, the Irish and the Welsh, ended when the Irish problem was settled by Ireland becoming independent. It was no longer the political creed that it had been for the previous century or so, and since then Britain has been unfolding in different ways. With the reforms in the 1990s and the re-instatement of the Scottish Parliament and so on, we actually see something that is quite different. There is really no historical imperative, if one wants to be British, to hang onto something which has that particular constitutional passion.

The other question you raised is spot-on as well. One of the fascinating things about most of the major proposals for a unitary national system of government in Australia that would involve abolishing the states, is that they have still presumed the existence of a written constitution in which the existence of those provinces or whatever would be constitutionally guaranteed and that they would usually end up having far stronger powers than local government and often stronger powers than state governments over quite a lot of things. They would actually be protected, including the right to raise revenue and all sorts of things. When you break them down and see what’s in them, many of our proposals for a unitary constitutional system have ended up looking a fair bit more federal than our existing federal constitutional system. That is a fact that has largely been lost in Australian political debate, especially once the cold war bit and we had a Labor government which was associated with a unificationist platform that looked like the Soviet Socialist Republic, and then conservative parties who were happy to stick with the federal system. I think the answer is that what we have called the unitary option, once we have started to devise and reinvent it in our own language, still relies fundamentally on the best parts of federal principle, not the worst parts, and the natural constitutional psyche of Australians is capable of taking the best from both traditions. But we don’t have that in the current system.

Question — Why didn’t we have the republic of the Riverina? We can throw a stone over to the Murrumbidgee to where it was. They were stopped from having a republic of the Riverina, and its capital city was Albury. Would you like to comment on the republic of the Riverina?

AJ Brown — I don’t think anyone was ever going to create a sovereign independent nation of the Riverina, but the proposals that the Riverina be its own colony or own state have occurred through history numerous times and have been extremely strong. There were two interesting things about that scenario. They firmly sit within the new state tradition, a very strong active decentralist federal tradition, and the Riverina would have been a very logical state. That’s one of the reasons why it developed its own name. Dunmore Lang translated it from Spanish because there was a state of South America that was called Entre Rios, because it defined an area between two big rivers. He got the name from them and converted it to Riverina.

The interesting thing about the Riverina is that most of the stalwart supporters for the Riverina new state came around by the 1930s to saying: this has been a big furphy. What we need is a proper British system of local government. What we need is a constitutional system where we have greater local government, so we have a Riverina local government in effect, or a number of more powerful councils and that local government is actually beefed up or built up. If we had that, the state’s relevance would continue to wither away and we would end up with a two-tiered system of government in effect, where you have the two important levels, British style: a national parliament and something closer to a local government. The Riverina new state proposals died out because most of its leaders came around to that line of thinking. It’s a very interesting example of how these ideas have interplayed in the field in different parts of Australia.

* This paper was presented as a lecture in the Department of the Senate Occasional Lecture Series at Parliament House on 22 April 2005.

[1] Jim Soorley (former Lord Mayor of Brisbane), ‘Do we need a federal system …’ in W. Hudson & A.J. Brown, eds, Restructuring Australia: Regionalism, Republicanism and Reform of the Nation-State, Annandale, NSW, Federation Press, 2004, p. 39.

[2] N.K. Blomley, Law, Space and the Geographies of Power. New York, Guilford Press, 1994, p. 114.

[3] B. Galligan, A Federal Republic: Australia’s Constitutional System of Government, Sydney, Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp. 32, 52–5; see also G. Sawer, Modern Federalism, London, Watts & Co, 1969, pp. 135, 179; J. Hirst, The Sentimental Nation: Making of the Australian Commonwealth, Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 2000; C. Saunders, ‘Dividing Power in a Federation in an Age of Globalisation’, in C. Sampford and T. Round, eds, Beyond the Republic: Meeting the Global Challenges to Constitutionalism, Leichhardt, NSW, Federation Press, 2001, p. 133.

[4] J. Hassan, ‘Two tiers out of three ain’t bad: Howard’, Government News, December/January 2002.

[5] J. Howard, ‘Reflections on Australian Federalism’, Address to the Menzies Research Centre, Melbourne, 11 April 2005.

[6] A.J. Brown, ‘One continent, two federalisms: rediscovering the original meanings of Australian federal political ideas’, Australian Journal of Political Science vol. 39, no. 4, 2004: 485–504; and ‘Constitutional schizophrenia then and now: exploring federalist, regionalist and unitary strands in the Australian political tradition’, Papers on Parliament no. 42, December 2004: 33–58.

[7] Brown, ‘Constitutional Schizophrenia …’, op. cit., p. 40.

[8] G. Maddox, ‘Federalism: or, government frustrated’, Australian Quarterly vol. 45 no. 3, 1973: 92–100.

[9] M.A. Schwartz, Politics and Territory: the Sociology of Regional Persistence in Canada, Montreal, McGill-Queen's University Press, 1974, p. 2.

[10] B. Galligan, ‘Federalism's ideological dimension and the Australian Labor Party’, Australian Quarterly vol. 53 no. 2, Winter 1981: 128–140.

[11] B. Galligan, A Federal Republic: Australia’s Constitutional System of Government, Sydney, Cambridge University Press, 1995, pp. 61, 198.

[12] I. Macphee, ‘Challenges for 21st century Australia: politics, economics and constitutional reform’, Griffith Law Review, vol. 3, 1994: 245; and ‘Towards a model for a two-tier government’, in Australian Federalism: Future Directions, Structural Change, University of Melbourne, Centre for Comparative Constitutional Studies, 1994.

[13] Business Council of Australia, Government in Australia in the 1990s: a Business Perspective, Melbourne, Business Council of Australia, 1991; and Aspire Australia 2025, Melbourne, Business Council of Australia, 2004.

[14] A Federal Republic, op. cit., pp. 61. 92, 122.

[15] G. Davis (ed.), The Future of the Australian Constitution, Brisbane, Griffith University, 1996, p. 14.

[16] A.J. Brown, ‘After the party: public attitudes to Australian federalism, regionalism and reform in the 21st century’, Public Law Review, vol. 13 no. 3, 2002: 171–190; and ‘Subsidiarity or subterfuge? Resolving the future of local government in the Australian federal system’, Australian Journal of Public Administration, vol. 61, no.4, 2002: 24–42.

[17] G. Jungwirth, in G. Patmore and G. Jungwirth, eds, the Big Make-Over: the New Australian Constitution, Sydney, Pluto Press, 2001, p. 135.

[18] B. Galligan, ‘State policies and state polities’, in B. Galligan (ed.), Comparative State Policies, Melbourne, Longman Cheshire, 1988, p. 291.

[19] S.R. Davis, ‘The state of the states’, in M. Birrell (ed.), The Australian States: Towards a Renaissance, Melbourne, Longman Cheshire, 1987, p. 21; G. Craven (ed.) Australian Federation: Towards the Second Century, Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, 1992, pp. 67–8.

[20] L.F. Crisp, The Australian Federal Labour Party 1901–195,. Sydney, Hale and Iremonger, 1978, pp. 23ff.; Galligan, A Federal Republic, op. cit., pp. 91ff.

[21] See A.J. Brown, ‘Can’t wait for the sequel: Australian federation as unfinished business’, Melbourne Journal of Politics, vol. 27, 2001: 47–67.

[22] Earle Page, ‘Plea for unification: an address’, 13 August 1917.

[23] J.B. Peden, Report of the Royal Commission on the Constitution, Canberra, Government Printer, 1929, p. 247.

[24] Engineers’ case 1920, per Knox CJ, Isaacs, Rich and Starke JJ. Amalgamated Society of Engineers v The Adelaide Steamship Company Limited and Others (1920) 28 Commonwealth Law Reports 129.

[25] S.J. Butlin, 1954, quoted in W.G. McMinn, A Constitutional History of Australia, Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 1979, p. 169.

[26] S.L. Winer, Political Economy in Federal States: Selected Essays, Cheltenham, Eng., Edward Elgar, 2002, p. 96.

[27] A. Wood, ‘Stealth missile for the States: the rise and rise of Federalism’, in Waldren (ed.), Future Tense: Australia Beyond Election 1998, Sydney, Allen & Unwin, 1999, p. 215.

[28] A. Winckel, ‘Vision of unification: John Boyd Steel's Constitution’, New Federalist, no. 6, 2000: 26–33.

[29] L.F. Crisp, Federation Fathers, Carlton, Vic., Melbourne University Press, 1990, 68ff.

[30] Ibid., pp. 49ff.

[31] N.J. Christie, ‘Evolution, Idealism and the Quest for Unity: Historians and the Federal Question 1880–1930’, in B.W. Hodgins et al., eds, Federalism in Canada and Australia: Historical Perspectives 1920–88, Peterborough, Ontario, Trent University, 1989, p. 353.

[32] B. Kingston, Glad, Confident Morning: Oxford History of Australia Volume 3, 1860–1900, Melbourne, Oxford University Press, 1993, pp. 57–9.

[33] Western Australian Parliamentary Debates, vol. ix, 1896: 850.

[34] T.C. Just, Leading Facts connected with Federation: Compiled for the Information of the Tasmanian Delegates to the Australasian Federal Convention 1891, Hobart, Government of Tasmania, Hobart, 1891, p. 34.

[35] Quiz (Adelaide), 1900.

[36] ‘Constitution Bill: Petition from Shoalhaven’, New South Wales Legislative Council Papers vol. 2, 1853: 3.

[37] See for example E.G. Whitlam, ‘A new federalism’, Australian Quarterly, vol. 43, no. 3, 1971: 6–17; and R.J.K. Chapman and M. Wood, Australian Local Government: the Federal Dimension, Sydney, Allen & Unwin, 1984, pp. 169–70.

[38] T. Abbott, ‘A republican federation of regions: reforming a wastefully governed Australia’, in Hudson and Brown, 2004, op. cit., p. 185.

[39] G. Martin, The Durham Report and British Policy, Cambridge, Eng., Cambridge University Press, 1972; M. McKenna, The Captive Republic: a History of Republicanism in Australia 1788–1996, Melbourne, Cambridge University Press, 1996, p. 29.

[40] Lord Durham 1839, quoted in Martin, op. cit., pp. 54–74; W. McMinn, op. cit., p. 36.

[41] A.C.V. Melbourne, Early Constitutional Development in Australia, St Lucia, Qld, University of Queensland Press, 1963, pp. 261, 310–28, 383–6; McMinn, op. cit., pp. 31, 48; McKenna, op. cit., pp. 29–30.

[42] Martin, op. cit., p. 69.

[43] Melbourne, op. cit., p. 237.

[44] D. Pike, Paradise of Dissent: South Australia 1829–1857, Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, 1957, pp. 39, 241.

[45] Melbourne, op. cit., pp. 188–9, 231–56.

[46] F.A. Larcombe, The Development of Local Government in New South Wales, Melbourne, Cheshire, 1961, p. 30; McMinn, op. cit., p. 37.

[47] Stephen, quoted in Melbourne, op. cit., p. 319.

[48] Gipps, quoted in Melbourne, op. cit., pp. 253, 337–8.

[49] H.E. Egerton, A Short History of British Colonial Policy, London, Methuen, 1893, p. 284; J.M. Ward, Earl Grey and the Australian Colonies 1846–1857, Melbourne, Melbourne University Press, 1958, p. 23; Larcombe, op. cit., p. 12; Melbourne, op. cit., pp. 275–353; McMinn, op. cit., p. 92.

[50] Wentworth, quoted in Melbourne, op. cit., pp. 344–51.

[51] Earl Grey, The Colonial Policy of Lord John Russell’s Administration, London, Richard Bentley, 1853, pp. 317–23, 427–51.

[52] Ward, op. cit., pp. 41–2; Larcombe, op. cit., pp. 25–6; McMinn, op. cit., p. 42.

[53] Melbourne, op. cit., pp. 342–6, 232–6, 323.

[54] Brown, ‘Constitutional schizophrenia’, op. cit., pp. 38, 50–51.

[55] Melbourne, op. cit., pp. 291, 297–301; McMinn, op. cit., p. 38.

[56] Macarthur, quoted in Melbourne, pp. 258–9.

[57] J. Howard, ‘Reflections on Australian Federalism’, op. cit.

[58] Galligan, 1995, op. cit., pp. 46–51.

[59] House of Representatives Standing Committee on Economics, Finance and Public Administration, Rates and Taxes: a Fair Share for Responsible Local Government, Canberra, Australian Government Publishing Service, 2003.

[60] A.J. Brown, ‘Regionalism and Regional Governance in Australia’, in R. Eversole and J. Martin, eds, Participation and Governance in Regional Development: Perspectives from Australia, Aldershot, Ashgate [forthcoming].

Prev | Contents | Next

Back to top