Politicians at War: The Experiences of Australian Parliamentarians in the

First World War

Aaron Pegram

Sometime around noon on 25 April 1915, a 35-year-old sergeant

of the Australian 1st Battalion lay mortally wounded in thick scrub above

the beach that would later be known as Anzac Cove. Having come ashore with the

second wave attack earlier that morning, men of the 1st Battalion were rushed

inland to a position on Pine Ridge to help reinforce the tenuous foothold

troops of the 3rd Brigade were holding in the face of growing Turkish

resistance. Stretcher-bearers came to carry the wounded man back down the

gully, but he refused. ‘There’s plenty worse than me out there’, he said, in

what was the last time he was seen alive.[*]

Sergeant Edward (Ted) Larkin was among 8,100 Australian and

New Zealand troops killed and wounded at Anzac within the first week of

fighting.[†]

His body was recovered during the informal truce with Turkish troops in the

following weeks, but the whereabouts of his final burial place remains unknown.

As such, he is commemorated on the Lone Pine Memorial, alongside 4,934

Australian and New Zealander soldiers killed on Gallipoli who have no known

grave. As a soldier, Larkin appears no different from the 330,000 men who

served in the Australian Imperial Force during the First World War, but as a

civilian, he was among a number of state and federal politicians who saw active

service with the AIF during the First World War.

According to figures compiled by the Commonwealth

Parliamentary Library, 119 Australian MPs saw active service in the First

World War: 72 were members of the House of Representatives, 44 were senators

and three served in both chambers. Among them were nine federal MPs who fought

while in office, and an estimated twenty state MPs who saw active service

abroad during their time in office.[‡] Not

only were these men who debated, decided and legislated for the young

Australian nation, but they, like many Australians, were personally affected by

the war and nation’s involvement in it. As the Labor member for Willoughby in

New South Wales as well as the NRL’s first full-time secretary, Ted Larkin was

among the 10,000 men who enlisted at Victoria Barracks in Sydney within a

fortnight of Britain’s declaration of war against Germany in August 1914.[§]

To a crowd outside the recruiting depot, Larkin announced this was ‘a critical

time for our Empire, and I deem it the duty of those holding public positions

to point the way’.[**]

The First World War casts an exceptionally long shadow over

Australian history. From a wartime population of 4.5 million people, the cost

of participating in the conflict was exceptionally high. Within four short

years, the AIF sustained over 215,000 casualties, of which 60,000 died on

active service, while countless others, and their families, lived with the

war’s psychological consequences for decades afterwards. Virtually every household

and community in Australia was affected by the fighting and debates over the

issue of conscription divided Australia along social, sectarian and political

lines. The war also had a deep and lasting impact on Australia’s political

community—not just in the form of the political issues that affected the nation

during the war, but on a more private level, impacting on serving politicians

in both state and federal politics whose sense of loyalty, duty and patriotism

to the broader British Empire led them to become active participants in the

fighting.

The First World War is often seen today as a costly and futile

slaughter of no real gain or outcome, but in 1914, Australians like Ted Larkin

were deeply and personally committed to Australia’s military commitment to the

conflict. This was mainly due to the fact that Australia was a dominion of the

British Empire and shared exceptionally close ties with Britain when war began.

The six self-governing British colonies had federated just thirteen years before

the outbreak of war, 20 per cent of the population residing in Australia had

been born in Britain and, on the international level, Britain still managed

Australia’s diplomatic relations with the rest of the world. These strong ties

to the ‘mother country’ meant there were few dissenting voices in Australia in

August 1914 when German troops invaded neutral Belgium, putting an invasion

force within 100 kilometres of the English Channel ports, and Britain declared

war.

Australia was automatically at war along with the rest of the

dominions when Britain declared war on Germany. This may seem absurd to modern

Australians, but the government at the time was willing to accept Britain’s

decision without question, believing that defending the rights of small countries

like Belgium and containing German expansionism in Europe were core interests

for Australia. News that Britain was at war with Germany came in the midst of a

federal election campaign where it received unanimous support from both sides

of politics. One of the earliest overtures took place at Horsham in Victoria,

weeks before war was declared, when the incumbent prime minister, Joseph Cook,

announced that if war broke out in Europe all of Australia’s resources would be

committed for the preservation of the British Empire. His opponent, the leader

of the Australian Labor Party, Andrew Fisher, echoed the sentiment at Colac

where he famously declared Australia would stand beside ‘our own to help and

defend [Britain] to our last man and last shilling’.[††]

Recruiting began for the Australian Imperial Force on 11

August in order to fulfil the government’s pledge to send Britain a military

force of 20,000 troops in the form of an infantry division and a light horse

brigade; but by the end of the year, more than 50,000 men were ready for active

service abroad. Outside Victoria Barracks, Ted Larkin urged all in public

office to lead by example and volunteer for overseas service, but the reality

was that very few members in state and federal parliament at the time would

have met the strict eligibility requirements. At the start of the war, the AIF

required applicants to be between the ages of 18 and 35, a height of 5 foot

6 inches and a chest measurement of 34 inches; since the average age of

federal MPs at the time was 43, most were either too old or unfit to serve.

Recruiting standards were lowered after Gallipoli as mounting casualties and

falling enlistment numbers resulted in a greater need to fill reinforcement

quotas, so it was not until later on in the war that most MPs could follow Ted

Larkin’s example.

In January 1916, at the age of fifty-one, the federal member

for Bendigo, Alfred Hampson, fronted the recruiting depot at Melbourne’s Town

Hall where he passed the medical test but was turned away because of his age.[‡‡]

Undeterred, Hampson tried a second time after losing his seat to Billy Hughes

in the 1917 federal election. After leaving parliament and lying about his age,

Hampson was eventually accepted into the AIF and served on the Western Front in

the final months of the war with the 2nd Light Railway Operating Company.[§§]

Some MPs had political and religious reasons that prevented

them from serving in the AIF, and certainly some felt a moral obligation to

their constituencies to remain in Australia. During the 1914 federal election,

the senior member of the federal Labor Opposition, Billy Hughes, suggested

suspending the election during the international crisis in support of a

government of national unity. Hughes’ proposal meant elected members would

return unopposed, but the idea was considered unworkable and was quickly

forgotten.[***]

Federal MPs who felt duty-bound to enlist took a leave of absence and generally

came from parties that occupied safe seats, while those in marginal seats were

more inclined to enlist after the 1917 federal election.

William Fleming, the federal member for Robertson (NSW),

enlisted as a private in 1916 following news that his old Labor opponent,

William Johnson, had been killed at Pozières. Fleming was still in camp when

his conservative seat was contested by Labor candidate Eva Seery—one of the

first women endorsed by a major party to contest the Australian Parliament—who

questioned the duration of his training and accused him of ‘playing at

soldiering’ to secure votes.[†††] An

ardent patriot who opposed conscription, Fleming’s personal decision to enlist

helped Hughes and his Nationalist colleagues brand themselves as the

‘Win-the-War’ party, conveying the message that they alone could lead Australia

to victory for the imperial cause. Fleming successfully retained his seat and

sailed for England five months later as a driver with the Australian Army

Service Corps. Promoted to sergeant, he was gassed at Péronne in France in

September 1918 and returned to Australia after the armistice.[‡‡‡]

Some politicians simply could not face the shame of not going

to the war. One was James O’Loghlin, the only sitting senator to serve

overseas, who enlisted in 1915 and declared to the Defence Minister, George

Peace, that ‘If you cannot put me in the firing line, put me as near to it as

you can’.[§§§]

Another was Granville Ryrie, a distinguished Boer War veteran and Nationalist

member for North Sydney, who wrote to his wife on 4 August 1914: ‘I couldn’t

look men in the face again, especially some of my political opponents whom I

have accused of disloyalty, if I didn’t offer to go. I simply cannot hold

back’.[****]

A major in the part-time militia, and commander of the 3rd Light Horse

Regiment, Ryrie typified a number of militia officers who held political

positions in the years after Federation. With substantial command and

leadership experience backed by years of overseas service, men like Ryrie were

fundamental in raising, training and commanding the newly formed AIF before it

sailed for the Great War. Promoted to brigadier general, Ryrie was given

command of the 2nd Light Horse Brigade which defended the Suez Canal in Egypt

against Ottoman incursions, then fought dismounted on Gallipoli, where his men

held the southernmost defences at Anzac. Wounded twice on Gallipoli, Ryrie

later led his men across the Sinai desert and took part in the long advance

across Palestine and into Jordan. He was awarded the Order of the Nile,

mentioned in despatches five times, and commanded the Anzac Mounted Division

before returning home to his electorate in 1919.[††††]

Ryrie

had a long and distinguished military career that would have helped further his

political aspirations in the years after the war, but there was at least one

New South Wales politician who had risen through the ranks of the pre-war

militia, and whose skills and command and leadership experience extended much

further than his time in politics. The Liberal member for Armidale, George

Braund, commanded the 13th Infantry Regiment on the eve of the First World War

and, on the formation of the AIF in August 1914, was appointed commander of the

2nd Battalion. Braund led his men ashore on Gallipoli on 25 April, and for two

days held an isolated position atop of Walker’s Ridge in the face of growing

Turkish resistance. Early on the morning of 4 May, Braund set off to brigade

headquarters via a short cut through the scrub. Slightly deaf, he failed to

hear a challenge from an Australian sentry who mistook him for a Turk and

killed him.[‡‡‡‡]

Ryrie

had a long and distinguished military career that would have helped further his

political aspirations in the years after the war, but there was at least one

New South Wales politician who had risen through the ranks of the pre-war

militia, and whose skills and command and leadership experience extended much

further than his time in politics. The Liberal member for Armidale, George

Braund, commanded the 13th Infantry Regiment on the eve of the First World War

and, on the formation of the AIF in August 1914, was appointed commander of the

2nd Battalion. Braund led his men ashore on Gallipoli on 25 April, and for two

days held an isolated position atop of Walker’s Ridge in the face of growing

Turkish resistance. Early on the morning of 4 May, Braund set off to brigade

headquarters via a short cut through the scrub. Slightly deaf, he failed to

hear a challenge from an Australian sentry who mistook him for a Turk and

killed him.[‡‡‡‡]

Larkin,

Fleming, O’Loughlin and Ryrie all equated war service with an unwavering

loyalty to the British Empire, but in South Australia, Australia’s entry into

the war affected the careers of a number of political figures in very different

ways. Germans were the largest non-British group of Europeans in Australia at

the time, and reflecting the large population of German migrants that settled

in South Australia in the nineteenth century, there were at least seven South

Australian MPs of identifiably German descent in parliament when Britain and

the dominions went to war with their homeland.

Larkin,

Fleming, O’Loughlin and Ryrie all equated war service with an unwavering

loyalty to the British Empire, but in South Australia, Australia’s entry into

the war affected the careers of a number of political figures in very different

ways. Germans were the largest non-British group of Europeans in Australia at

the time, and reflecting the large population of German migrants that settled

in South Australia in the nineteenth century, there were at least seven South

Australian MPs of identifiably German descent in parliament when Britain and

the dominions went to war with their homeland.

All seven members (five Liberal and two Labor) came under

intense public scrutiny at a time when Germans and all things German were

openly subjected to hostility. As rumours of atrocity stories from the fighting

in northern France and Belgium filtered home, locals directed their anger at

some of the state’s most respected German citizens. Among them was the

Attorney-General and Industry Minister, Hermann Homburg, whose offices in

Adelaide were raided by soldiers armed with rifles and fixed bayonets after war

was declared. Homburg resigned in January 1915 to avoid embarrassing the

government in the forthcoming election, writing of a campaign ‘of lies and

calumnies against me ... because I am not of British lineage’.[§§§§]

The German MPs were considered something of an electoral handicap when the

state government lost the election, and mistrust intensified the following year

when it was clear that voters in German districts had contributed to South

Australia’s rejection of conscription at the 1916 referendum. The war gravely

affected the political careers of those German MPs holding office in South

Australia, with just one of the seven remaining in parliament by November 1918.[*****]

After Gallipoli, the AIF returned to Egypt where it effectively

doubled in size in preparation for the fighting on the Western Front. As soon

as the AIF arrived in France in mid-1916, the main challenge facing Australians

was matching casualties with a steady stream of willing volunteers. Eight

months of fighting on Gallipoli had cost the AIF 26,000 casualties, the same

number lost in eight weeks in France in costly actions at Fromelles, Pozières

and Mouquet Farm.

In Australia, state-based recruiting committees increased

their efforts in urging young men to enlist in the AIF, and certainly local

members used public meetings and gatherings to urge the men of their electorate

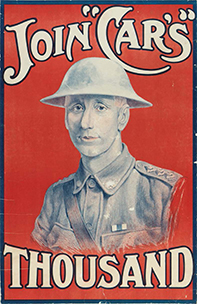

to volunteer. Some led by example, such as Ambrose Carmichael, the Labor member

for Leichhardt and Minister of Public Instruction in the New South Wales

Parliament, who signed on as soon as the extended age requirement permitted him

to do so. In November 1915, Carmichael announced he would personally ‘raise a

thousand rifle reserve recruits’ from the rifle clubs of New South Wales.[†††††]

Enlisting as a private at the age of 44, Carmichael and his willing volunteers

entered Broadmeadow Camp in Newcastle where they formed the basis of the newly

raised 36th Battalion—a unit that colloquially became known as ‘Carmichael’s

Thousand’.

Carmichael

was eventually commissioned as a lieutenant and embarked with the battalion for

the training camps in England before proceeding to the Western Front in

November 1916. As part of the 3rd Division, the 36th Battalion spent the

following six months in relatively quiet Houplines sector near the town of

Armentières, where it carried out a regimen of patrolling and trench raiding

throughout the ensuing winter. In January 1917, Carmichael was seriously

wounded in the face and hands when a German raiding party attacked the

Australian positions and was evacuated to England for treatment and recovery.

For conspicuous gallantry in organising his platoon under heavy German

bombardment, and for ‘setting a splendid example of courage and determination’,

Ambrose Carmichael was awarded the Military Cross.[‡‡‡‡‡]

Carmichael

was eventually commissioned as a lieutenant and embarked with the battalion for

the training camps in England before proceeding to the Western Front in

November 1916. As part of the 3rd Division, the 36th Battalion spent the

following six months in relatively quiet Houplines sector near the town of

Armentières, where it carried out a regimen of patrolling and trench raiding

throughout the ensuing winter. In January 1917, Carmichael was seriously

wounded in the face and hands when a German raiding party attacked the

Australian positions and was evacuated to England for treatment and recovery.

For conspicuous gallantry in organising his platoon under heavy German

bombardment, and for ‘setting a splendid example of courage and determination’,

Ambrose Carmichael was awarded the Military Cross.[‡‡‡‡‡]

Carmichael missed the fighting at Messines, but he was

promoted to captain and rejoined his unit in Belgium in time to participate in

the Third Battle of Ypres. He was wounded a second time a Broodseinde on 4

October, receiving gunshot wounds to his arms and legs which necessitated his

evacuation to England and repatriation to Australia in January 1918. Carmichael

was a strong advocate of conscription, but his return to Australia in the wake

of the defeat of the second conscription referendum led him to appeal for

another ‘great sustained recruiting campaign’[§§§§§]

as voluntary enlistments for the AIF plummeted to an all-time low. He was not

expelled from the Labor party after the split over conscription, but he

gradually drifted from the party as he invested all his energy in stimulating

voluntary recruiting. In February 1918, Carmichael became the chairman of the

New South Wales Recruiting Committee, raising yet another ‘Carmichael’s

Thousand’ and returning to France with a reinforcement group for the 33rd

Battalion in September 1918. He arrived just several weeks before the armistice

was signed, and did not see any further fighting.

Carmichael returned to Australia and state politics where he

was revered as something of ‘an over-age and mercurial war hero’[******],

but his energy and personal sense of conviction in believing in the cause for

which he himself had fought was shared by at least one other state politician

who had enlisted in the latter stages of the war.[††††††]

Bartholomew Stubbs, the Labor member for Subiaco in the Western Australian

Legislative Assembly, enlisted as soon as the eligibility requirements permitted,

signing on in Perth at the age of 43 in January 1916. As a member of the

Western Australian recruiting committee, Stubbs had publicly voiced his beliefs

about the justice in the Allied cause and had spoken at a number of recruiting

platforms in the Subiaco area, but believed that leading by example was the

best course of action. To reporters of The Daily News, Stubbs urged

‘middle-aged men without children or other ties, or whose children have grown

up, [to] volunteer before the young married men’.[‡‡‡‡‡‡]

After a period of training at Blackboy Hill, east of Perth,

and the Royal Military Academy, Duntroon, Stubbs was commissioned as a second

lieutenant and embarked for the Western Front with a reinforcement group for

the 51st Battalion. In Flanders in early August, he sent a cablegram confirming

he would run again as the Labor candidate in the upcoming Western Australian

state election, and on 12 September retained the Subiaco seat unopposed. Two

weeks later, Stubbs was shot in the chest and killed during the AIF’s highly

successful attack at Polygon Wood near the Belgian town of Ypres. According to

an account written eighteen years after the war, the loss of such a popular

commander resulted in soldiers of his platoon seeking battlefield justice on a

group of surrendering German soldiers whose pleas for mercy were swiftly

ignored.[§§§§§§]

Stubbs was given a hasty battlefield burial by his men, but the location of his

temporary grave marker was lost in subsequent fighting. Stubbs therefore has no

known grave, and is today commemorated on the Menin Gate Memorial in Ypres amid

the names 6,100 Australians who remain missing from the fighting in Belgium.

Commenting

on the makeup of Australian politics in the decades after the war, Chris

Coulthard-Clark writes that the First World War was something of a catalyst for

a military influx into state and federal politics.[*******]

The divisive issues such as conscription, inflation, wage freezing and export

embargoes had the effect of hardening political views in Australian society,

and caused a number of returned servicemen to enter politics before the

Armistice. Throughout the 1920s, men who had risen through the ranks of the

AIF, occupied command positions or were highly decorated during the war were

naturally drawn to a career in politics. Victoria Cross recipients Lieutenant

Arthur Blackburn and Private William Currey both entered state politics on

their return to Australia, as did General Sir William Glasgow, Major Generals

Sir Neville-Howse and Sir John Gellibrand, Brigadier General Harold ‘Pompey’

Elliott and Colonel Edmund Drake-Brockman.

Commenting

on the makeup of Australian politics in the decades after the war, Chris

Coulthard-Clark writes that the First World War was something of a catalyst for

a military influx into state and federal politics.[*******]

The divisive issues such as conscription, inflation, wage freezing and export

embargoes had the effect of hardening political views in Australian society,

and caused a number of returned servicemen to enter politics before the

Armistice. Throughout the 1920s, men who had risen through the ranks of the

AIF, occupied command positions or were highly decorated during the war were

naturally drawn to a career in politics. Victoria Cross recipients Lieutenant

Arthur Blackburn and Private William Currey both entered state politics on

their return to Australia, as did General Sir William Glasgow, Major Generals

Sir Neville-Howse and Sir John Gellibrand, Brigadier General Harold ‘Pompey’

Elliott and Colonel Edmund Drake-Brockman.

Some rose to prominence after their war service. Wilfrid Kent

Hughes, cabinet secretary and government whip in the Victorian Legislative

Assembly in the late 1920s, served with the 3rd Light Horse Brigade on

Gallipoli where he was wounded at the charge at the Nek in August 1915. Serving

again during the Second World War, he was captured by the Japanese at Singapore

in February 1942, and spent three years imprisoned at Changi, Formosa and

Manchuria. Returning to politics, he served as the Member for Chisholm (Vic.)

in the House of Representatives from 1949 to 1970. Thomas White, the Minister

for Trade and Customs in the first Lyons Ministry, had been a pilot in the

Australian Flying Corps. Brought down over Mesopotamia in 1915, White spent

three years a prisoner of the Turks, and was the only Australian to escape

Ottoman captivity. Another was Jim Fairbairn, the Minister for Air and Minister

for Civil Aviation in the first and second Menzies ministries, who had served

as a pilot in the Royal Flying Corps in the Great War. Fairbairn was brought

down near Cambrai, France, in February 1917 when his aircraft was set upon by a

Jasta of German scouts. With his arm and aircraft shredded by

machine-gun fire, and his face badly burned, Fairbairn crash-landed on the

other side of No Man’s Land and spent the following twelve months in a German

prison camp.

At least one-third of senators and members in federal politics

in the late 1940s were First World War veterans, but it is important to

recognise that the conflict also shaped the lives of some of Australia’s first

female politicians. Although Australian women had the right to vote and be

nominated for federal election in 1903, it was not until after the First World

War that the first female members of parliament were elected. A strong advocate

of the suffrage movement and women’s rights and welfare, Edith Cowan was the

first woman elected to an Australian parliament after her victory in the

Western Australian election in 1921. During the war years, Cowan worked for a

number of patriotic and humanitarian aid organisations, which included the

Australian Red Cross Society, for which she helped with fundraising and

starting up the Welcome Home for returned soldiers. For this, Cowan was awarded

an OBE after the war, but during it, she was an ardent pro-conscription

campaigner and an active member of the Perth Recruiting Committee. Red Cross

work played a crucial role in involving women in the war effort and in public

life, but the war also had a profound impact on women like Ivy Weber, the first

woman elected at a general election in Victoria, whose war years were spent

maintaining family and home. Long before she entered politics in the 1930s,

Weber received the devastating news that her husband, Lieutenant Thomas Mitchell

of the 59th Battalion, had been killed in action at Bapaume.

Just like any other community in Australia at the time, the

First World War had a significant impact on the personal and private lives of a

number of state and federal politicians whose sense of loyalty, duty and

patriotism led them to become active participants in it. Some led by example,

not wanting to hide behind the excuse of public position to shirk their duty

and do what many political figures were expecting of other men, while others,

with extensive experience in raising, training and commanding soldiers, helped

raise a voluntary army that served with distinction on Gallipoli, in

Sinai–Palestine and the Western Front.

Perhaps one of the reasons why their story remains little

known is the fact that no one memorial recognises the service and sacrifice

made by both state and federal MPs during the First World War. The three

serving MPs who died in the First World War are commemorated on the bronze

cloisters of the Roll of Honour at the Australian War Memorial, alongside

102,000 Australian men and women who died on active service since before the

Boer War. But they appear without distinction, rank or profession pointing to

the very unique community to which they belonged. One of the few sites of

commemoration is a small tablet to Ted Larkin and George Braund in the New

South Wales Legislative Assembly chamber, which was unveiled in November 1915

and is still there today. The inscription thereon reminds us that the First

World War had a significant impact on the lives of all Australians, which

included those in public office: ‘In time of Peace they readily asserted the

rights of citizenship. In time of War they fiercely protected them’.

Question — My grandfather is Senator O’Loghlin from

South Australia who you referred to earlier. You somehow inferred that he was

shamed into enlisting. Maybe I inferred that wrongly but it sounded like that.

You didn’t mention that he was 62 at the time which makes it a bit difficult

for him to be embarrassed about not going. He did prevail on the Minister of

Defence to allow him to go and he was eventually put in command of a troopship,

appointed a lieutenant colonel and did two trips to Egypt at the age of 62

while a serving senator.

Aaron Pegram — That inference that he was somehow

shamed is not correct. I think his remarks to the Defence Minister really point

to the fact that he, among many politicians, felt enlisting was his patriotic

duty. I believe that he also had a very distinguished career in the militia

beforehand, which may have shaped his view that if he could be of service he

certainly wanted to go, irrespective of his age.

Question — I am assuming that the members of parliament

concerned kept their positions in parliament while serving and that they would

have received leave of absence. What arrangements were typically made for

dealing with constituent affairs and for campaigning in elections?

Aaron Pegram — This is an issue that I really couldn’t

get my head around. The men who enlisted in the AIF appear to be from very safe

seats that were not going to be contested. I haven’t found any examples of it

in the Australian experience, but certainly in New Zealand there were two

members of parliament from opposite sides of the house that agreed to pair

during the war so as to not affect the voting numbers.

But in terms of dealing with local affairs I really get the

sense that it was done from afar and these men did take a leave of absence. I

get the sense that men who go off to the war occupy safe seats, that they are

in a safe position because their constituency is backing them 100 per cent and

no one is going to contest their seat; it is almost seen as being disloyal or

unpatriotic. In terms of how they manage their constituencies, I will have to

get back to you on that one.

Question — I was wondering if you have detected any

kind of pattern from the people who enlisted who were serving as MPs as to

whether or not they were predominantly pro-conscription or predominantly

anti-conscription and whether or not that tells you something about the

political climate at the time?

Aaron Pegram — The interesting thing about the two

conscription referenda is that they polarise Australia. There is no argument

about whether or not Australia should be involved in the war, it is about

whether men should be going under their own volition. There isn’t a pattern. I

get the sense that even though there are pro- and anti-conscriptionists, the

men who feel patriotic and compelled to enlist still do so for one reason or

the other. So there isn’t a pattern I can detect and that is probably because

there is a very small percentage of men who enlist while serving members. But

certainly it is an interesting question that we can ponder on.

Question — You indicated at the start of your address

that the age limit for enlistment was 35. There were a significant number of

MPs who eventually fought. Did they enlist after that age limit was relaxed, or

did some of them tell a few lies?

Aaron Pegram — Some evidently did tell a few lies. If

we take the example of William Johnson, the former Labor MP who was killed at

Pozières, I think he was in his mid-50s. He would have enlisted in 1914, so I

think there were a few porkies being told there. There is also the increasing

age limit as the war progresses. Certainly the men who enlisted in 1914 were

among the fittest and strongest in the AIF during the war. That all changes

once we go the Western Front where we have this struggle to try and maintain

reinforcement quotas so the age limit does bump up. That enables a number of

MPs to enlist. There is a sense that, certainly at the federal level, the

outcome of the 1917 federal election ultimately decides for some people whether

they should enlist or not. There is the case of Alfred Hampson who was defeated

by Billy Hughes. Even though he has tried before, the election of 1917 is

certainly something that is a great impetus. So that is another thing, as long

as the war continues the age limit gets bumped up and more men are being drawn

in.

There is also the issue of the militia men who were serving in

politics at the time. These men are Boer War veterans who have commanded

regiments. Irrespective of their age, they are capable officers, which at the

time the Australian Imperial Force simply doesn’t have. This is an

all-volunteer army that has been formed for the exclusive purpose of serving

overseas in the Great War and it needs commanders. Granville Ryrie I think was

in his 50s on the eve of the First World War so there are a number of factors

that are at play there. Certainly Ted Larkin was amongst the very few that

would have fit the age requirements in 1914.

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page