Papers on Parliament No. 61

May 2014

Helen Irving* "The Over-rated Mr Clark?: Putting Andrew Inglis Clark’s Contribution to the Constitution into Perspective"

Prev | Contents | Next

Every commemoration needs its Doubting Thomas.

This is the role I have assumed. It is not my intention to question whether

Andrew Inglis Clark deserves recognition or honour. I do not doubt for a moment

that he does. Clark, I am happy to agree, was a distinguished liberal democrat,

a man of vision, knowledge and talent, one of the significant contributors to

the progressive politics of his era and the achievement of Australia’s

federation. But I do want to question the many claims that have been made for

him above and beyond these attributes. I want, in particular, to challenge his

elevation to the status of ‘Founding Father’ or ‘primary architect’ of the

Australian Constitution,’[1] not to mention ‘the most important ideas man of our whole nation in

terms of structure, in terms of the current laws and institutions that we have

today’.[2] I also want to question the equally persistent claim that Clark

valiantly (albeit unsuccessfully) proposed a bill of rights for the

Constitution.

My scepticism finds expression in several

questions:

Was Andrew Inglis Clark the ‘primary architect’ of the Constitution?

Clark’s claim to be the architect of the

Australian Constitution rests on the role he played in the framing of what I

will refer to as the 1891 constitution bill (with a lower case ‘c’ and a lower

case ‘b’).

Let me be blunt. The 1891 constitution bill is a

fine, historical document, but it is not the Constitution (upper case

‘C’) of the Commonwealth of Australia. It was not adopted by any parliament or

approved by any sovereign. It went nowhere. It was, in reality, a draft, with

no official status, any more than Clark’s own (now celebrated) draft—the one he

circulated for discussion prior to the 1891 Convention—or Charles Cameron

Kingston’s similar-purpose draft, for that matter. For sure, the 1891 bill was

to prove useful in the later process of drafting the Constitution, but that

fact does not make it the Constitution or even an earlier version of the

Constitution. Indeed, none of the authors of the 1891 constitution bill can

claim to be the primary or even secondary architect(s) of the Constitution.

This is not just pedantry, or a type of reverse

‘stone soup’ in which the person who puts the final pinch of salt in the pot is

credited with being the chef. It is based on an evaluation of the relationship

between the 1891 constitution bill and the Constitution—the one that was

approved by popular referendums and passed by the imperial parliament in 1900:

the one with which Australia works today. The Constitution and the 1891

constitution bill have many similarities, but they are different documents.

The Constitution was written at the 1897–98

Federal Convention (the second Convention), by delegates from five colonies—a

total of 54 men, only 17 of whom had been at the 1891 Convention. Most

significantly, the majority were popularly elected. They were representatives. Unlike the appointed

members of the 1891 Convention, they represented the Australian voters. This

fact influenced their approach. The delegates at this Convention unambiguously

affirmed that their work was to be their own—that it was neither their role nor

their intention to follow the 1891 constitution bill. Indeed, on the opening

day of the second Convention, Edmund Barton, the Convention leader, declared

that, ‘[w]hile ... a great deal of instruction may be derived from the Bill of 1891,

the business of this Convention is to arrive at a conclusion, not under the

influence of the previous work, but by its own efforts’.[3] He added,

somewhat inelegantly (the Hansard reporters got it down verbatim): ‘This is the

first Convention directly appointed by the people, and therefore the inference

from that is that the desire of the people is that, as far as possible, this

Convention shall originate the Constitution’.[4] The

Convention needed to take into account the mandate of ‘the people’. Furthermore,

the delegates knew that their work—a bill for the Commonwealth of Australia

Constitution Act—would be subject to the people’s approval in the referendums

which, under the colonial Enabling Acts that framed the Convention, were to be

a precondition for submitting the bill to the imperial parliament. To maintain

that a constitution bill written by political appointees and a Constitution

Bill written by elected representatives (and popularly approved) are

effectively the same thing is to neglect this vital, democratic distinction.

It is true that the second Convention did not

entirely adhere to its undertaking to start afresh, and many of the 1891

constitution bill’s provisions wound up in the Constitution, but influence and

a similarity in words do not make an early document the equivalent of a later

document, any more than the many similarities between the Australian

Constitution and the United States Constitution make the latter an early

version of the former. (We would readily accept—would we not?—that the

similarities between the Australian and the US Constitutions do not give the

framers of the latter the status of framers of the former.) Clark was not a

member of the second Convention. He could not, at least from this perspective,

have been the ‘primary architect’ of the Constitution.

Was Clark an ‘architect’ of the Constitution all the same?

Many people, I am sure, will be unpersuaded by

my claim that the 1891 constitution bill should be distinguished from the

Constitution (and, indeed, the Justices of the High Court are likely to be

among them, since the court has frequently and freely conflated the two in

using history as a guide to constitutional interpretation[5]). But even if

the 1891 bill and the Constitution were effectively continuous, Clark’s contribution

would still need to be put into perspective.

Clark, as noted, produced and circulated a draft

‘constitution’ prior to the first Convention as a means of getting discussion

going, and, certainly, many of the provisions in Clark’s draft ended up in the

1891 constitution, as well as in the Constitution. It has been

calculated (and frequently repeated) that, of the 96 sections in Clark’s draft,

86 ‘found a recognisable counterpart in the final Constitution’.[6] I haven’t tried to replicate this count, but there is no reason to

think it is not accurate. However, another count is also relevant. Of those 86,

a very significant number also find a ‘recognisable counterpart’, to say the

least, in the United States Constitution, and a further substantial number in

Canada’s Constitution, the British North America Act of 1867 (a quick skim of

the latter reveals at least 20 parallel provisions).[7] It is, in

fact, readily evident that the very large majority of the provisions in Clark’s

draft are versions of provisions found in these other instruments. Some are

virtually cut and pasted. Clark did not pretend otherwise. Indeed, in his

‘Memorandum to Delegates’ which accompanied his draft constitution bill, he

stated that he had examined both, and (understating his borrowing from the

Canadian) had ‘followed very closely the Constitution of the United States’.[8]

The borrowing of American provisions is

unsurprising. A year earlier, a federal conference had met in Melbourne to

consider whether to proceed with the (hitherto unsuccessful, but long-held)

goal of federation. The Conference had agreed to do so, and, from the start,

Clark, one of the participants, had persuaded them to follow the US form of

federalism. It is quite likely, therefore, that a good deal of the Australian

Constitution would have looked like a good deal of the American Constitution,

whether or not Clark had provided a draft with much of its wording taken from

the American. At Clark’s urging, at the same time, the Conference had rejected

the Canadian form of federalism (on the ground that it was too centralist).

Still, in non-federal respects, they knew that Canada had exactly the

institutional features they were looking for: responsible government under the

British Crown, with a bicameral parliamentary arrangement that accommodated a

federal system. So, it is also not surprising that, at the 1891 Convention,

many of Canada’s non-federal provisions were copied: notably, those governing

the role of the Governor-General, certain institutional features of the Houses

of Parliament, and many of the heads of power of the Canadian House of Commons.

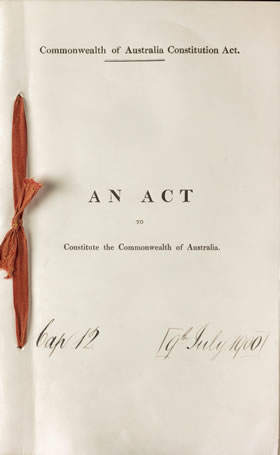

Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act 1900 [original public record copy] (1900). Gifted by the House of Commons, United Kingdom, to the Australian Government and people. Courtesy of Parliament House Gift Collection, Department of Parliamentary Services, Canberra, ACT

But there is more than numerical tallies to take

into account in assessing Clark’s contribution to the 1891 constitution bill,

and through that to the Constitution. Other members of the 1891 Convention also

played a major part. Charles Cameron Kingston (as Dr Bannon has reminded us)

also wrote a draft constitution in 1891 for consideration by the Convention,

and some of its provisions found their way into the Constitution. We should

note, in particular, the industrial arbitration power (section 51(xxxv)), which

found no counterpart in the US or Canadian constitutions, but in Australia’s

Constitution was to underpin the great ‘Australian settlement’ between capital

and labour that stood as a central pillar of Australian politics for much of

the twentieth century, helping secure workers’ rights and industrial stability.

Many other members of the Convention also

proposed provisions that were to prove important in the Constitution. Notably,

Sir Samuel Griffith, Chair of the 1891 Convention’s drafting committee, wrote

significant parts of the constitution bill, and his skill as a draftsman was

critical in capturing the ideas of the Convention in legally functional words.

But, of course, if one is persuaded by my claim about 1891, Griffith’s words

cannot be regarded as the words of the Constitution, any more than

Clark’s. In any case, what Alfred Deakin described as Griffith’s ‘terse, clear

style’ did not altogether survive into the Constitution itself, although

Griffith’s input was invaluable, and ‘the arrangement of the provisions, the

major themes, and the relations between the parts [of the Constitution], retain

much of his imprint’.[9] But this is influence, not authorship.

Of these three men, Kingston, I suggest, has the

greater claim to the title of ‘architect’. Apart from anything else, Kingston

was a key player in both Conventions (and in the critical negotiations with the

British Government in 1900 prior to the passage of the Constitution Bill by the

imperial parliament). Griffith and Clark were not. Critically, they were absent

from the second Convention. Poor old Griffith had no choice; he would

undoubtedly have been elected to that Convention, had elections been held in

his colony. But Queensland literally could not get its Act together, and

remained unrepresented. In Tasmania, Clark, too, would certainly have been

elected. Unlike in Queensland, Tasmania held elections for the Convention, but

Clark was not a candidate. Why not?

It seems inconceivable that Clark, the ardent

Americanist, who knew about and admired the Philadelphia Convention of 1787,

could have failed to appreciate the chance this second Convention offered to be

part of history. It is routinely said that Clark had scheduled a trip to the US

in 1897 and this prevented his taking part. This simply is not convincing.

Clark had been to the US before. He could not possibly have thought travelling

more important than the chance of writing the Constitution. He could have

changed his plans, postponed his trip. Furthermore, he had plenty of time to do

so. Elections for the Convention, which took place in March 1897, had been

anticipated for more than a year (the relevant Tasmanian Enabling Act was

passed in January 1896). Everyone who hoped to take part would have been on the

alert well before the event. In any case, Clark was not overseas at the

relevant time; ‘he participated actively in the Tasmanian Parliament’s

consideration of the Adelaide [session of the second Convention] draft Bill,

and he participated in the Melbourne Debates from outside the Convention in

1898’.[10]

It is further said that Clark’s appointment in

1898 as a Justice of the Supreme Court of Tasmania prevented his participation

in the Convention. This, too, does not add up. Even if Clark had been tipped

off the year before his appointment was announced, it could not have affected

his decision regarding the second Convention. None of the candidates and none

of the elected delegates knew when they started that the Convention would

continue into 1898. Indeed, the official commitment was to have two sessions,

and for these to be no more than 120 days apart (accordingly, the second

session could not have started in 1898, if the first session was to begin, as

planned, and as happened, in the first half of 1897).

According to the Enabling Acts, a new draft

Constitution Bill was to be written at the first session; the recess that

followed would give the colonial parliaments the opportunity to consider the

bill and make suggestions for amendment. These suggestions would then be

debated at the second session. The Convention thus began its work confident of

winding up before the end of the year. No one knew until almost the last minute

that they would have to reconvene after the second session. Unexpectedly,

however, the number of proposed amendments was very large, and, since the

Victorian delegates had to return to their colony for a general election, time

ran out for debating them. A third session was scheduled. At a pinch—although

no pinch was needed—Clark could still have taken part in the two 1897 sessions,

been surprised or wearied or frustrated (as they all were), by the need for a

third, and then been replaced by another Tasmanian (there was no rule against

this—four of the Western Australian delegates were replaced between sessions).

Still, it has to be accepted that, until that Eureka!

moment when some lucky researcher stumbles across a letter (‘Rosebank, Hobart,

February, 1897. Dear X, I have decided not to stand for election to the

Convention because ...’) no one can say for sure why he acted, or failed to act,

as he did. The Tasmanian delegation does not seem to have known either; it is

understood that they even promised to hold a place open for him at the

Convention, were he to change his mind. My own guess is based on nothing more

scientific than a long-distance psychological assessment. In a work published

long after both men’s deaths (so it cannot have influenced Clark’s opinion),

Alfred Deakin described Clark as, among other things, ‘nervous, active, jealous

and suspicious in disposition’.[11] There is

evidence to support this character sketch. In at least one source (a poem),

Clark revealed an extraordinary capacity for bitterness and deeply felt resentment.

Deakin, unnamed but readily identifiable, was his target. The poem, written

post-Convention, accuses Deakin of untrustworthiness: ‘Of broken faith—so

cunningly devised/That none could safely say that he had lied’ (and of

‘pos[ing] as a patriot’ and finding happiness in ‘floods of talk that

simpletons believe’, and more). Richard Ely has concluded that it is a response

to Deakin’s failure, as Commonwealth Attorney-General in 1903, to keep his

promise (it seems he made one) to appoint Clark to the newly created High

Court.[12]

Reading backwards to 1897, I guess that Clark,

who was also known to be unhappy that his proposals for the 1891 constitution

bill were not followed as closely as he had hoped, was temperamentally

unwilling to expose himself to a similarly frustrating experience, and just did

not want to do it. He pulled the plug, or took his bat and ball, and went home.

I am happy for this to be refuted. But is it such a terrible thing to suggest?

Must Clark’s reasons necessarily have been outside his control or external to

his own choice? Cannot he simply have declined to be part of the show? Surely

we can accept that Clark was a human being, a man who perhaps could not bear

the idea of working again with men he did not care for, and with no certainty of

a reasonable outcome or, indeed, of any outcome at all. Clark was certainly

unhappy with the actual outcome. Unlike Griffith—also absent from the second

Convention—he opposed the final Constitution Bill. He ended the decade, in this

respect, not as a ‘Founding Father’, but as an ‘anti-father’. He may very well

have rejected the title of ‘primary architect’ of the Constitution himself.

Did Clark propose a bill of rights for

the Constitution?

In assessing Clark’s contribution, special

attention is needed to one additional claim. It concerns a provision that did

not end up in the Constitution. Clark, it is said, proposed or even urged that

Australia’s Constitution should include a bill of rights. This claim has

several dimensions. It is stated as a fact, and it is also used to bolster

twenty-first century claims that the framers of the Constitution were

neglectful, perhaps even contemptuous of entrenched rights, and that—had they

only listened to Clark!—Australia would not now be alone in the democratic world

(or, so it is lamented) without a bill of rights.

Let us focus a little more closely on what Clark

sought to do. Clark’s draft constitution did not include a bill of rights, and

nor did it include much in the way of provisions that might be recognised as

counterparts to provisions of the US Bill of Rights. However, the 1891

constitution bill—‘most likely’ due to Clark[13]—did include

a provision that resembled a section of the US Constutution’s 14th

Amendment, and, subsequently, Clark was to urge the second Convention to retain

and expand it. That provision, as it stood in 1891, included a prohibition on

any state’s abridging any ‘privilege’ or ‘immunity’ of citizens from other

states,[14] or denying the ‘equal protection of the laws’ to any person within

the state’s jurisdiction.

This sounds very significant (although the 14th

Amendment is not a bill of rights) and it may well have proven to be in the

long run, had the provision been adopted. But, the Constitution’s framers

cannot have known this, because, at the time they were working, US case law

would have given them relatively little guidance. Indeed, the whole idea of

proposing a bill of rights (whether based on the first ten Amendments, or the

14th Amendment, or both) had a very different context from the one we know

today.

If we imagine Australians contemplating a

US-style bill of rights in the late nineteenth century (as we must), we need to

work with the available jurisprudence. The US provisions, at that time, had

only rarely been drawn upon to protect what we would recognise as rights today.

Indeed, there was relatively little rights jurisprudence to speak of in

nineteenth-century America. The Bill of Rights applied only to Congress—to

federal laws—and none of its individual rights was ‘incorporated’ against the

states (via Supreme Court interpretation) until well into the twentieth

century. Numerous laws that breached or denied or overlooked the rights that we

now believe to be protected by the US Bill of Rights went unchallenged in the

nineteenth century. There was, indeed, very little to give Australians the idea

that such a bill in their own Constitution would have been superior to the

legislative or common-law protections of rights with which they were familiar.

In any case, Clark did not propose a bill of rights. As noted, he proposed a

version of a section of the 14th Amendment.

What, then, was the status of 14th Amendment

jurisprudence at the end of the nineteenth century? The 14th Amendment applied

only to state laws; it was not until the 1950s that ‘reverse incorporation’ was

implied by the Supreme Court and ‘equal protection of the laws’ came also to

bind Congress. Certainly, a guarantee of ‘due process’ could be found in the

Fifth Amendment (which applied to federal laws), but, again, in the nineteenth

century, there was almost no ‘due process’ jurisprudence. However, when it

began to flourish soon after Australia’s federation—in the so-called ‘Lochner

era’[15]—it was wielded by the Supreme Court for more than three decades to

strike down the sort of laws that protected, among other things, the

progressive working conditions that were flourishing in Australia at that time.

The framers of Australia’s Constitution cannot have known this, either, but

(when claims are made that they thwarted Clark’s vision of a rights-bearing

constitution) it is worth considering that such laws might not have survived,

had Australians followed the US with a ‘due process’ provision in their

Constitution.

In the recess between the first two sessions of

the 1897–98 Federal Conventions, Clark (as Tasmanian Attorney-General) was to

propose an expanded version of the ‘14th Amendment,’ adding ‘due process’.

However, although the Tasmanian Parliament forwarded it to the Convention as a

proposed amendment to the Constitution Bill (as it stood in mid-1897), it was

not included in the Constitution. The version of the 14th Amendment that found

its way from the 1891 constitution bill into the Constitution Bill, up until

the final Convention session in 1898 (when it was removed), included only

‘privileges and immunities’ and ‘equal protection’. To sound like a broken

record, there was relatively little jurisprudence for either of these clauses

in the US in the nineteenth century, and indeed, some of the few cases to be

found would not commend themselves to today’s advocates of constitutional

rights. I am thinking, for example, of the unsuccessful claim by American

suffragists that the denial of the right to vote for women breached the

guarantee of ‘privileges and immunities’ of citizenship. This claim, made more

than once in the second half of the nineteenth century, was breezily dismissed

by the Supreme Court, and American women had to wait until 1920 to achieve what

Australian women had gained without a constitutional guarantee, almost two

decades earlier—the federal right to vote. Now, none of this is Clark’s fault.

But it does put into perspective what he proposed with his section of the 14th

Amendment, and what he would have expected it to do. And it also puts into

perspective, I think, the claim that his vision was recognisably modern (in a

twenty-first century sense), and that he was, in this respect, a prophet whose

words fell on deaf or stubborn ears.

Was Clark nevertheless a ‘Founding Father’?

We should not, I respond, use the language of

‘fathers’. This goes to my most significant protest. Even if the 1891

constitution bill had been adopted by the colonial parliaments and enacted by

the imperial parliament and had become the Constitution, the elevation

of its framers as ‘Fathers’ or ‘Founding Fathers’ should be resisted. There are

many reasons, not the least being that it is a type of linguistic barbarism to

speak of fathers giving birth. (I know you will object that ‘fathers’ is

metaphorical. But, I invite you to think about this metaphor and whether it is

really what we imagine it to be, nothing more than a universal, economical

shorthand for ‘important people’. If it is only that, why not call these

important people ‘mothers’? After all, that fits better with the metaphor of

giving birth, doesn’t it?)

Mercifully, ‘Father’ is used relatively rarely

in the scholarly literature about Clark, so perhaps I do not need to spend too

much time rebutting the title. Let us keep it that way. The more significant

problem, at least for my protest, is the uncritical veneration of any

historical individual or collection of individuals. Veneration of persons leads

to veneration of their work (this has happened very strikingly in the US). We

lose sight of the collective, contextual effort; we draw a veil over the human-ness

of the persons involved, and the work itself becomes all the harder to change.

Constitutions written by ‘Founding Fathers’ are accorded a type of sacred

authority, as if coming from the hands of inimitable, supernatural persons. By

implication, no one today is capable of achieving what these persons achieved.

No one should damage their unsurpassable handiwork.

I do not suggest that the men—and women!—who

brought about federation should be forgotten or swallowed up in the crowd of

history. They are certainly worthy of recognition, gratitude, and not a little

awe. But they were human beings, not gods, and nor were they ‘fathers’ who—in

an extraordinary, agamogenetic act—managed to give birth.

Conclusion—Clark does deserve recognition

What, then, was Clark’s contribution to the

Constitution, for which admiration is justified and for which he should be

remembered? Sir Henry Parkes, Premier of New South Wales, had instigated the

1890 Conference, but Clark effectively took it over. He dominated the debate, and

his insistence that Australia should follow the United States, rather than

Canada, in its form of federalism, triumphed (so much so that, having started

out by suggesting that an Australian constitution should be modelled on the

Canadian, Parkes concluded by claiming, indignantly, that he had never proposed

such a thing).

Clark suggested that Australia should copy the

US Constitution because he wanted to preserve states’ rights, and he admired

America’s way of doing this. Clark, we note, had not actually visited America

before the 1890 Conference; his first visit was to come later that year (one

breathes an anachronistic sigh of relief, to know that it lived up to his

expectations!). He returned home, ready to commit his enthusiasms to paper at

the 1891 Convention. But to what, finally, did he commit?

Clark’s attachment to states’ rights and the

American model extended to equal state representation in the Senate, regardless

of population. This arrangement, combined with the almost co-equal powers given

to the Australian Senate and the House of Representatives, were the major

targets of criticism of the Constitution Bill during the referendum campaigns

that followed the bill’s completion. The ‘anti-Billites’ protested that the

Constitution was undemocratic. They were unsuccessful, but they had a point.

One need not reject the design of the Senate to note that its representational

disproportions would never have survived the democratic standards of even the

early decades of the twentieth century, let alone today.[16] For good, or

ill, Clark persuaded the colonial leaders to accept the American model as their

own. In this way, he left his most significant stamp on Australia’s history.

Secondly—and let me be more positive on this

point—Clark was original in one particular respect that deserves to be better

known. He proposed that what he wanted to call the Supreme Court of Australia

(which, in the Constitution, became the High Court of Australia) should serve

as the final court of appeal for Australian law. The Judicial Committee of the

Privy Council was, in Clark’s proposed provision, to be deprived of this power

of appeal. Ultimately, the provision turned up in the Constitution Bill, albeit

a little watered down on the insistence of Britain, but with the important

principle retained. In the bulk of constitutional matters, the High Court was

always to have the final say. Furthermore, the Commonwealth Parliament was

empowered to pass laws closing off appeals to the Privy Council in any

remaining matter, a power that it exercised, step by step, over the decades.

That Australia has long controlled its own laws is due, in no small part, to

Clark’s vision.

In this respect,

although I resist the language of ‘fathers’, I will be more than happy to

accept what others have cogently proposed: Clark’s status as one of the

visionaries (if not architects) of the Australian republic, when—as ultimately

it must—it finally comes about.

[1]* The author is grateful to the Clerk of the Senate,

Rosemary Laing, for presenting this paper on her behalf, in her unavoidable

absence.

Deane J, Theophanous v. Herald & Weekly Times Limited (1994) 182

CLR 104 at 172. Clark is similarly described as ‘Principal Architect of the

Constitution’ on a portrait in the Hobart registry of the Federal Court of

Australia.

[2] Peter Botsman (author of The Great

Constitutional Swindle, Pluto Press, Sydney, 2000). Interview: The 7.30 Report, ABC, 20 December 1999.

[3] Official Record of the Debates of the

Australasian Federal Convention, Adelaide, 23 March 1897, Legal Books,

Sydney, 1986, vol. 3, p. 11.

[4] ibid.

[5] See Helen Irving, ‘Constitutional interpretation, the

High Court, and the discipline of history’, Federal Law Review,

vol. 41, no. 1, 2013, pp. 95–126.

[6] John Williamson, ‘Clark, Andrew Inglis’, in Helen Irving

(ed.), The Centenary Companion to Australian Federation,

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, England, 1999, p. 345.

[7] A small handful can also be found in the Federal Council of Australasia Act (Imp) of 1885, which was

drafted by Sir Samuel Griffith.

[8] John M. Williams, The Australian

Constitution: A Documentary History, Melbourne University Press,

Carlton. Vic., 2005, p. 67.

[9] Helen Irving, ‘Framers of the Constitution’, in Tony

Blackshield, Michael Coper and George Williams (eds), The

Oxford Companion to the High Court of Australia, Oxford University

Press, South Melbourne, 2001, p. 285.

[10] William G. Buss, ‘Andrew Inglis Clark’s draft

constitution, Chapter III of the Australian Constitution,

and the assist from Article III of the Constitution of the United States’, Melbourne University Law Review, vol. 33, no. 3, 2009, p.

721.

[11] Alfred Deakin, The Federal Story: The

Inner History of the Federal Cause 1880–1900, Melbourne University

Press, Parkville, Vic., 1963, p. 32. He also considered him to be a ‘sound

lawyer, keen, logical and acute’.

[12] Richard Ely, ‘The poetry of Inglis Clark’, in Richard Ely

(ed.), A Living Force: Andrew Inglis Clark and the Ideal of

Commonwealth, Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies, University of

Tasmania, Hobart, 2001, p. 185.

[13] John M. Williams, ‘Race, citizenship and the formation of

the Australian Constitution: Andrew Inglis Clark and the “14th Amendment” ’, Australian Journal of Politics and History, vol. 42, no.

1, January 1996, p. 11; J.A. La Nauze, The Making of the

Australian Constitution, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Vic.,

1972, p. 230.

[14] Section 117 of the Constitution which prohibits states

from discriminating against residents of other states, on the ground of

residency, is the end result of this proposal.

[15] Following Lochner v. New York 198

US 45 (1905).

[16] At least the Constitution included direct election of the

senators, something the 1891 constitution bill did not: in the latter, again,

the 1891 bill followed the US Constitution, which did not provide for elected

senators until the passage of the 17th Amendment in 1913.

Prev | Contents | Next