Papers on Parliament No. 61

May 2014

David Headon "Four Degrees of Separation: Conway, the Clarks and Canberra"

Prev | Contents | Next

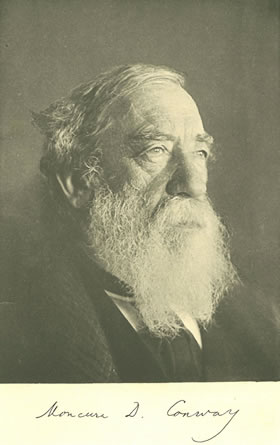

In October 1883, American Unitarian minister and

controversial ‘freethinker’, Moncure Conway, delivered four public lectures in

Hobart. He had been invited by Andrew Inglis Clark who, as Conway would recall

in his fascinating travel memoir, written late in life, ‘told me of a small

club of liberal thinkers who met together to read liberal works and discuss

important subjects’.[1]

Conway’s understanding of the small Australian

island colony had been shaped and, as he wrote, ‘darkened’ at a distance by his

reading of Marcus Clarke’s classic Australian novel, For the Term of His

Natural Life, published less than a decade before, in 1874. Conway remarked

on the book’s ‘tragical power’, an impression dramatically reinforced by an

apparition of a ‘gloomy forest’ that he experienced at night, mid-ocean, on the

ship voyage from Melbourne to Launceston. However, many years later, reminiscing

about his southern sojourn in the memoir, My Pilgrimage to the Wise Men of

the East (1906), he noted that ‘All gruesome imagination about Tasmania

vanished when I found myself in the delightful home circle at Rosebank,

residence of the Clarks at Hobart’.[2] Conway

delighted in the serious discussions that took place in the Clark study,

discussions, he remembered fondly, on ‘high themes’.[3]

Moncure Conway’s visit to Tasmania had a

profound impact on both men, the 51-year-old, London-dwelling, rebellious

Virginian and the 35-year-old Tasmanian. It would alter the course of their

lives.

Two weeks after Conway’s departure from Hobart

back to the Australian mainland, Andrew’s wife Grace gave birth to the couple’s

fourth child, a boy. They named him Conway Inglis Clark. An architect in later

life, Con Clark would play an unobtrusive yet distinctive role in Canberra’s

grand foundation narrative—the result, at least in part, of his father’s

political and cultural affinities and preoccupations, and the three and a half years

that Con spent in the north-east of the United States, from May 1905 to

December 1908.

Conway Clark was working in New York in 1907

when, on 14 November, his much-loved and admired father died suddenly in his

home, the elegant ‘Rosebank’, apparently of a ruptured blood vessel in the

heart. He was 59. The very next day, on 15 November, in far-off Paris, Moncure

Conway died peacefully in his apartment, aged 75. While this symbolic

connection is not quite the equal of the extraordinary 4th of July, 1826,

Independence Day 1826, that witnessed the deaths of esteemed American

Revolutionary fathers, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, there is nonetheless a

neat accord in the historic link in death between the American Conway and the

Australian Clark. As with Jefferson and Adams, from their first meeting they

too would maintain an active correspondence for the rest of their lives, a

correspondence based on mutual affection, as well as common interests,

attitudes, reading, and a like-minded philosophical and spiritual stance.

Photograph of Andrew Inglis Clark’s home, ‘Rosebank’, Battery Point, Hobart.

Image courtesy of the University of Tasmania Special and Rare Collections, http://eprints.utas.edu.au/11793

Through an assessment of selected aspects of the

lives and careers of Andrew Inglis Clark and Moncure Conway, and using as a

sounding board those American writers and thinkers that they most admired (such

as Tom Paine, Ralph Waldo Emerson and Walt Whitman), this paper will reveal

some surprising ties that bind them. Conway Clark and Canberra enter the frame

briefly, at the end. My discussion will concentrate on two compelling

individuals, and the cluster of radical ideas that shaped them, passed with

enthusiasm in correspondence between them, and contributed to the articulation

of a new democratic nation in the south.

In his seminal essay, ‘The Future of the

Australian Commonwealth: A Province or a Nation?’, written in late 1902 or

early 1903, Andrew Inglis Clark quotes with approval Professor J.A. Woodburn’s Causes

of the American Revolution, and that writer’s acknowledgement of how

ridiculous it would be to account for the American Revolution merely as the

result of the ‘imposition of a tax’. ‘Rather’, as Woodburn suggests, and Clark

obviously endorses, ‘the great movements of history have been the result of

moral and spiritual forces which, gathering for centuries, have needed only

favourable circumstances for the manifestation of their power’.[4] We better understand the dimensions of Clark’s imposing legal and

constitutional career if we consider some of those ‘moral and spiritual forces’

that he absorbed. To do this, we must start early.

Clark was born in Hobart on 24 February 1848,

the exact day of the proclamation of the Second French Republic. Perhaps this

was an omen. His parents were warm and loving, Andrew’s younger brother

Carrell, or ‘Tiff’, remarking in his unpublished ‘Personal Memoir’ that it was

a ‘sacred treasure’ to have known them.[5] Clark’s

father, Alex, and his mother, Ann, were Baptists—she devout, he not so much.

Clark’s two sisters and five brothers were subject to a clearly articulated

social code that insisted on no smoking, drinking, gambling or dancing. The

Hobart Baptist Church’s doctrinal machinations in Clark’s youth, on the other

hand, were quite the opposite. Biblical interpretation, the rituals of the

communion, were bitterly contested.[6] After a

literal full immersion baptism in his early 20s, Clark soon after rejected

Baptist strictures, not just withdrawing his participation but actually moving

in a meeting that his parish be dissolved (which, for a short time, it was).

We know that from an early age Clark had an

admiration for the United States. During his middle teens, as the American

Civil War raged, he became a staunch supporter of the Union, expressed

primarily as a rejection of what he would always refer to as the ‘hideous’

institution of slavery.[7] Clark’s career path in his father’s successful engineering firm

appeared assured when, in the late 1860s, and barely in his twenties, he became

a qualified engineer and the firm’s business manager.

This apparently settled, predictable world

changed irrevocably in the decade of the 1870s, and the young Clark was himself

the main catalyst. In 1872, a milestone year, he evidently went on strike,

defying the family’s chosen vocational path and becoming articled to R.P.

Adams, the colony’s long-serving Solicitor-General. He was called to the Bar in

1877. By mid-decade, Clark had embraced Unitarianism. He began writing poems,

and became increasingly radical in his politics as he gathered about him an

exuberant group of like-minded mates. One of them, A.J. Taylor, would later

become the Librarian of the Tasmanian Public Library. Taylor’s eloquent

obituary upon Clark’s death in 1907 provides us with genuine insight into the

engaging personality of his close friend. He brings Clark to life:

Intense to a degree, and enthused with a

divine unrest, that soon made him a leading spirit in all movements having for

their object the uplifting of humanity ... The convictions that governed him then

governed him up to the time of his death; and at no period of his life could it

be said that he proved false to the principles that he professed, or betrayed

the trust reposed in him. Generous by nature ... he was a passionate advocate for

the true democracy which means the affording of equal opportunity to all men ...[8]

Clark’s commitment to this ‘true democracy’ had,

by 1878, become so combative (under the influence of American political

theory), and public, that the Mercury newspaper

censured him for ‘holding such very extreme ultra-republican, if not

revolutionary, ideas’.[9] He properly belonged, the paper sneered, ‘in a band of Communists’.

While such claims were nothing but a nineteenth-century version of routine News

Ltd pejoratives, Clark’s speeches, toasts and debates, at sometimes rowdy

venues such as the Macquarie Debating Club, the American Club and, in

particular, the Minerva Club, along with his growing list of publications, are

instructive markers of a rapidly maturing intellect. A sharp, enquiring,

independent intellect. Richard Ely’s creative phrase, his ‘disputatious

dynamism’, fits nicely.[10] Clark’s mates dubbed him ‘the Padre’.[11]

The list of contents of the twelve issues of the

short-lived periodical, Quadrilateral, edited by Clark through the calendar

year, 1874, adds some depth to this portrait of the artist (and thinker) as a

young lawyer. The title page declared the journal’s thematic directions:

‘Moral, Social, Scientific and Artistic’. This is a fair summary of intent, for

the journal included articles on the French Republic, John Stuart Mill and the

Australian poets, Adam Lindsay Gordon and Henry Kendall; two pieces, in 1874

note, on ‘Our Australian Constitution’; and, in keeping with the era,

especially in the United States, no less than five articles on phrenology and

two on spiritualism.

|

|

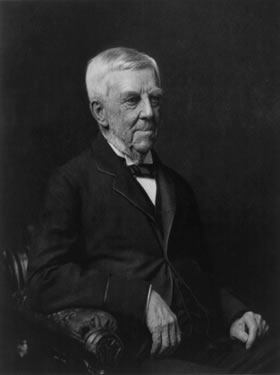

Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1803–1882, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003670025/

|

Walt Whitman, 1819–1892, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, http://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/00649765/ |

Of significance for this paper are two articles

on America’s most important nineteenth-century writers, Ralph Waldo Emerson and

Walt Whitman. Clark may have written both. Regardless, the sentiments expressed

under his editorial imprimatur add substance to a bold statement in the

journal’s second issue (that we know he definitely did write) when he referred

to ‘a universal Church of conscience and Commonwealth of Righteousness’.[12] The two Americans are essentially proposed as exemplars of this new

order.

One of the articles, ‘The Teaching of Emerson’,

praises the Transcendentalist author for his strong egalitarian instincts, his

mysticism embracing the religions and philosophies of both West and East, and,

above all, his determination to resist any hint of pedagogy in his writings in

favour of stimulating, provoking and inspiring his readers. For Emerson, the

purpose of books was not just to inform but, rather, to ‘lead [a person] to

think ...’[13]

This last phrase is Quadrilateral’s. The

long piece on Whitman, with its assertion of the American poet’s claims to

greatness and written in response to the publication of the uncompromising

‘Democratic Vistas’ essay of 1870 and the 1872 iteration of Leaves of Grass,

deserves its own literary recognition as one of the earliest and most searching

Whitman analyses to appear in Australia to that point. The ‘good gray poet’ is

lauded as a ‘true artist, prophet, teacher ... revealer’, a ‘Genius, Poet’—and

notably, a writer with special relevance to Australia:

[Whitman’s] utterances [are] more capable

than those of any European teacher of guiding the Australias to that moral

unity which alone can afford a basis for that nationality, which, through

whatever difficulties and windings, they must one day arrive at, or decay.[14]

The cluster of lengthy excerpts in the Quadrilateral

article, drawn from some of Whitman’s finest Civil War Drum Taps poems,

are astutely chosen by someone comfortable discussing Whitman’s work—his

subjects, poetic innovations, politics and provocative moral and spiritual

stance. This was Whitman for an antipodean audience, and in 1874. Surprisingly

early.

The 1870s decade shaped the young Andrew Inglis

Clark and, it would appear, a number of those close to him. Clark’s ‘boys’, as

they would be called, responded to his ‘ideals and aspirations’, as Alfred

Taylor remembered, and his firm principles. In his 1876 toast to the

Declaration of Independence, at the American Club, Clark foreshadowed an

enlightened future where the life principles he had forged would be:

... permanently applicable to the politics of

the world & the practical application of them in the creation &

modification of the institutions which constitute the organs of our social life

to be the only safeguard against political retrogression.[15]

Shift now to 1883, a

second eventful year in Clark’s life, when he learned from his mainland friends

that two Melbourne Unitarians, influential banker and lay preacher, Henry Gyles

Turner, and his associate, Robert J. Jeffray, had invited a celebrated American

Unitarian minister, Moncure Daniel Conway, to deliver a series of lectures in

their city. Conway tells us in his 1906 memoir that the invitation came about

because both Turner and Jeffray had made occasional visits to his London

church, South Place Chapel, the famed home of ‘freethinkers’ in Finsbury,

London.[16]

But what were the American’s credentials? His

attraction for an Australian audience?

Where do you start?

The career of Moncure Conway, son of Virginian

slave-holding Methodists, is straight out of Ripley’s Believe It Or Not.

As Paul Collins puts it in his terrific yarn, The Trouble with Tom—The

Strange Afterlife and Times of Thomas Paine (2005), Conway was ‘a veritable

Forrest Gump of the Victorian world’.[17]

Author of over seventy publications, Conway

provided the best summary of his Gump-like life in the ‘Dedication and Preface’

to his two-volume, Autobiography—Memories and Experiences, written late

in life, about the time of Australian federation:

The eventualities of life brought me into

close connection with some large movements of my time, and also with incidents

little noticed when they occurred, which time has proved of more far-reaching

effect ... I have been brought into personal relations with leading minds and

characters which already are becoming quasi-classic figures ... [already]

invest[ing] themselves with mythology ...

In my ministry of half a century I have

placed myself, or been placed, on record in advocacy of contrarious beliefs and

ideas. A pilgrimage from proslavery to antislavery enthusiasm, from Methodism

to Freethought, implies a career of contradictions.[18]

It was this extraordinary life pilgrimage, his

internationally publicised ‘contrarious’ advocacy of the liberating qualities

of ‘freethought’, that surely appealed to his Australian sponsors in Melbourne,

and to Andrew Inglis Clark.

Moncure Daniel Conway, 1832–1907

Moncure Conway was a promoter’s dream. This was

the man who, a Methodist circuit rider in Pennsylvania, stumbled upon a

community of Elias Hicksite Quakers, was overwhelmed by their spirit and

harmony, and changed his denominational affiliation and, in turn, his life

course, almost immediately. This was the rabid slavery-defender who, after

reading Emerson’s essays, struck up a lifelong friendship with the Concord

divine, travelled to Boston to undertake a Doctor of Divinity degree at

Harvard, became a Unitarian minister and outspoken abolitionist, and in the

process befriended virtually every significant writer of what F.O. Matthiessen

labelled the ‘American Renaissance’—among them, Henry David Thoreau, Nathaniel

Hawthorne, the Alcotts, George Ripley, Ellery Channing and Theodore Parker.

Conway met and befriended Walt Whitman in New York, before the poet met

Emerson. He was the go-between. Later, he looked after the publication rights,

in England, of Whitman, Emerson and his close friend in later years, Samuel

Clemens (Mark Twain); he championed Margaret Fuller, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and

Louisa May Alcott; he lobbied Abraham Lincoln about the detail of the

Emancipation Proclamation; he went to London in 1863 to raise funds for the

Union cause, and stayed on, in the first instance for 21 years as the minister

for the South Place Chapel, reputedly ‘the oldest and largest association of

free and independent thinkers in the world’[19]; and he

produced fine biographies of George Washington, Emerson, Thomas Carlyle and

Giuseppe Mazzini. Each of these works was widely acclaimed during his lifetime,

though none could rival the international impact of his 1894 two-volume

biography of Thomas Paine—the American Revolutionary writer who President

Theodore Roosevelt dismissed as a ‘filthy little atheist’. As Australian

scholar John Keane, in his majestic 1995 biography of Paine puts it: Conway’s

study today is ‘the standard ... still considered by every authority of Paine [to

be] the key reference’.[20]

In 1883, ‘Marvellous Melbourne’, Sydney and

Hobart played host to a bona fide celebrity. The spare details of Conway’s

Australian stay are these: he was in the country for two and a half months,

delivering at least thirteen lectures in Melbourne, four in Hobart, and an

unknown but large number in Sydney. His Melbourne and Hobart series were

advertised as Conway’s ‘Lectures for the Times’, to be delivered by the ‘finest

intellect in the southern hemisphere’, on marketable subjects such as ‘Mother

Earth’, ‘Woman and Evolution’, ‘Development and Arrest in Religion’, ‘The Pre

Darwinite and Post Darwinite World’, ‘Emerson’, ‘Shakespeare’, ‘America’ and, a

very popular one wherever he delivered it, ‘Demonology and Devil Lore’.[21]

With the benefit of hindsight, we know that when

he embarked on his epic 1883–84 journey, Conway’s religious, cultural and

social attitudes and beliefs were undergoing change, his secular stance

hardening, his interest in the world’s non-Christian religions growing.[22] In his memoir he states that, in Australia, ‘Some handling of

religious themes was expected of me, but my opening lecture (on Darwin) must

have revealed to the keen-eared sectarians heresies of which I was not yet

conscious’.[23] In the lecture to which he refers, he did put his argument bluntly:

‘[After Darwin] Not only could not man any more look upon the world with the

same eyes as before, but the new Genesis called Evolution was necessarily

followed by a new Exodus from the land of intellectual bondage’. Here, the

conscious allusion is to his mentor Emerson’s famous opening to the culture-redefining

‘Nature’ essay (1836), where he states that: ‘The foregoing generations beheld

God and nature face to face; we, through their eyes. Why should not we also

enjoy an original relation to the universe’.[24]

On his Australian trip, Conway acted on this

momentous invocation with audacity. In an article on Queen Victoria,

intentionally placed in the Sydney Evening News to coincide with his

first visit to that city, he critiqued the dowager Queen, warts and all. The

English people remained fiercely loyal to the Crown, Conway wrote, but as for

Victoria Regina, ‘a Queen less loved, or even cared for, never reigned in

England’.[25] And more: ‘She is variously objected to as morose, morbid, stingy,

grasping, ugly, sullen, ill-humoured, and torpid, if not stupid’. Australian

audiences had a taste of what was to come.

In Tasmania, in front of attentive Hobart

crowds, including Clark and his ‘boys’, Conway’s heresies directed at

prevailing community mores multiplied: churches, he observed in lecture one,

were ‘propagating superstition’[26]; in the

anti-war second lecture, ‘Woman and Evolution’, with informed reference to

Brahmin, Babylonian, Iranian and Rabbinical creation myths, he declared that

while Evolution was ‘giving women more courage, more strength, more

self-respect’, female equality would only be inevitable if a ‘ “reign of peace”

could be appointed’; his message for Australian orthodox Christians in lecture

three was, as he described it with Tom Paine-like trenchancy, ‘At the very

moment this dogma of the Trinity was formed, the humanity of Christ was doomed’[27]; and in the final talk on ‘The Martyrdom of Thought’, he ‘argued at

length against the creed of Christianity’, spoke of the ‘death’ of God, and

concluded with a few pithy sentences drawn from a key source, Tom Paine’s Rights

of Man.[28]

Such incendiary remarks did not go unchallenged.

There was a conservative backlash, the Launceston Examiner maintaining

that ‘Moncure Conway proved a frost in Tasmania’, but if that was so, the fire

certainly burned bright within the cosy Rosebank circle of friends. One

observation by Conway in his final Hobart lecture may well have been directed

at his set of new companions when he stated that ‘the real martyrdom of thought

[occurred when] young men of promise were brow-beaten into mean conformity with

Conservative codes when their brilliant talents should be bestowed to freeing

their fellow men’.[29] This was surely Conway’s antipodean call to arms.

Did this challenge provide new inspiration for

Andrew Inglis Clark’s evolving, ostensibly secular views? We don’t know for

sure. What we do know is that he and Conway established a friendship during the

short visit that endured. In a letter from Conway to Clark written in Sydney

shortly after his Hobart visit, the American was already ending his

communication with love to ‘Mrs Clark ... [and] the children’, and he drew

attention to the alteration to his standard salutation, shifting from the

polite ‘Mr Clark’, to the very English informality of ‘My dear Clark’.[30] When he heard while still in Sydney about the Clark family’s new

arrival, he was tickled. His response, a delightful one, is worth quoting in

full:

I must not let even one mail go without

congratulating you on the birth of your new boy, and gratefully acknowledging

your exceeding goodwill in giving him my name. Gratefully—yet rather

tremblingly,—for now I must try and ‘live up to’ that baby, in order that he

should not have reason in the future to regret the confidence of his parents.

But I deeply appreciate this mark of your friendship, which is very dear to me.

I feel with you that in the future we shall have thoughts that must pass and

repass between us. Hobart, by you and your circle of ‘Friends in Council’, has

been made a beautiful souvenir of my visit to the Antipodes.[31]

While it is common knowledge amongst Clark

scholars that the Italian republican Mazzini’s portrait hung on the walls at

Rosebank, perhaps on every wall the story goes (see Paul Pickering’s comments

in this volume pp. 68–71), less well-known is that Moncure Conway was up there

as well. In a letter written to Conway some fifteen years after the Australian

trip, Clark mentions that his tight group continued to meet in the Rosebank

library ‘where your portrait looks down upon us as we exchange our thoughts

upon our respective experiences in the two worlds in which we live’.[32]

The fifteen or so years between Conway’s

‘beautiful souvenir’ letter, and Clark’s endearing missive to his friend

written on Tasmanian Judges’ Chambers letterhead, 1883–99, effectively bookend

a remarkably productive and eventful period for both men. Shortly after his

return to London from his southern ‘pilgrimage’, Conway informed Clark in May

1884 that he had resigned from his South Place Chapel ministry in London, after

21 years of polemical preaching, to devote himself to writing and, as he said,

‘[giving] lectures from time to time in America’.[33] Conway would

write prolifically in his later years. Clark’s notable trajectory into

Tasmanian and national public life over the same period has been amply

documented elsewhere, including in this issue of Papers on Parliament.

My interest lies in the evidence for an emergence of identifiable Conway

preoccupations in Clark’s work. As expected, the dominant themes of Conway’s

Australian lectures do frequently surface in Clark’s array of socio-cultural

writings in the ensuing years. John Reynolds, Henry Reynolds’ father and the

first serious Edmund Barton biographer, in his 1958 Australian Law Journal

article on Clark puts it succinctly: ‘[Conway] the American divine,

abolitionist, publicist and author ... exercised a considerable influence upon

his host’s thinking upon ethical and social problems’.[34] While

Reynolds does not pursue the statement in any detail, there is ample evidence

for its validity.

Clark’s 1884 article, ‘An Untrodden Path in

Literature’, enlarging on the new religious trend in theosophy, surely had as

its stimulus Conway’s experiences in India, immediately after the Australian

stay, when the American met the controversial Madame Blavatsky, together with a

significant number of Indian political and religious figures.[35] Alfred Sinnett’s book, Esoteric Buddhism (1884), a cult hit

in Victorian England and a cited source for Conway, was also studied closely by

Clark. His mid-1880s Minerva Club presentation, ‘A Critical Approach to

Religion’, drew heavily on Conway’s philosophical peregrinations while in

Australia, Clark also advocating ‘intellectual emancipation’, the need for the

liberated thinker to estimate impartially the claims of ‘the various religious

beliefs of mankind as moral forces’, along with ‘the respective claims of

science and intuition’.[36] The sentiments are straight out of the Emerson/Conway songbook.

Clark’s 1886 Minerva Club essay, ‘The Evolution of the Spirit’, begins with two

sentences that could well have been Conway’s own: ‘[S]ince Emerson, Carlyle and

Darwin wrote, the course of thought in the world has been changed. No man now

thinks as he thought before their ideas became known to him’.[37]

It was inevitable that Clark would visit the

country that had steadily become his primary moral and political/legal compass.

And he did, in 1890, embarking on the first of three trips, and meeting many

Americans who further shaped his ideas and his life path—political movers and

shakers, as well as a host of cultural, literary and religious figures, among

them high-profile Unitarians in Boston. One individual stands out from the

rest. Moncure Conway—there is that man Gump again—provided his Australian

friend with a letter of introduction to the feted New England man of letters,

the ‘Autocrat of the Breakfast Table’, Dr Oliver Wendell Holmes. As it happens,

Dr Holmes was out of town, and he asked his lawyer son, the jurist Oliver

Wendell Holmes (1841–1935), to look after the Australian visitor while in

Boston. As John Reynolds points out, meeting this new acquaintance would be,

for Clark, a defining moment:

The two men immediately became friendly, a

friendship which continued in spite of geographical separation ... With Clark’s

strong predilection towards American institutions and his study of American

history, it is safe to assume that Holmes had much influence in the final

development of his thinking upon the structure and working of the Australian

Constitution.[38]

As the career arcs of both men rose sharply in

the later 1890s and early years of the new century, they drew strength from a

mutually beneficial correspondence. Holmes would spend a remarkable thirty

years, 1902–32, on the bench of the United States Supreme Court.

In 1905, a few years after Clark’s third and

last American trip, the opportunity arose for his architect son Conway (Con, as

he was called) to pursue his promising architectural career in America. He

lived first in Boston, and this was no accident. Through Moncure Conway, Andrew

Inglis Clark had made many Unitarian friends when staying in the Unitarian

Church’s most populous city. On his arrival, Con house-sat for a family of one

of these Unitarian connections, the Cummings, at 104 Irving Street, Cambridge.

The Cummings, husband and wife, we know from other sources, met through

Harvard-based philosopher William James. Edward Cummings, a former Harvard sociology

professor, became the Unitarian minister for the influential South

Congregational Church in Boston, which for many years dedicated itself to the

task of alleviating the plight of the under-privileged. Edward resolutely

implemented the church’s motto, ‘That They May Have Life More Abundantly’ (a

favourite biblical phrase of another Australian Clark, Charles Manning Hope).[39]

|

|

Oliver Wendell Holmes, 1809–1894, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2003653451/

|

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, 1841–1935, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, www.loc.gov/pictures/item/npc2008006912/

|

The Cummings’ son, Edward Estlin, ten years old

when Con was in Boston, would go on to become one of America’s most famous modernist

poets, e e cummings, he of the non-negotiable small ‘i’ who wrote some of the

twentieth century’s most admired nature and love poems.

In Boston, Con Clark worked for the prestigious

firm of Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge, or, as he mischievously tagged it in one

of many letters home to his father, ‘Simply, Rotten and Foolish’.[40] The University of Tasmania Library has a selection of these

letters, son to father, written over a number of months in 1905 and, later, in

New York, in 1907, where Con had his last job. The last letter in the archival

collection takes us to within several months of his father’s death.[41]

It is apparent in the first letters in the

correspondence that Con made sure that he did the right thing by his father,

including meeting all Andrew’s ‘Cambridge friends’, and undertaking the

obligatory pilgrimage to Concord—Emerson country—and Lexington, site of the

shot heard round the world. On at least two occasions Con also attempted to

meet up with the man after whom he had been named. We don’t know whether he was

successful in meeting Moncure Conway, but he skited to his dad that, searching

for the right words to introduce himself, he ‘worked out quite a masterpiece’.[42] Andrew must have been chuffed. As the correspondence progresses,

Con proved himself to be something of a student of the contemporary American

political scene. This, too, must have pleased his ailing father.

When he finally returned home in December 1908

(the same month that ‘Yass–Canberra’ was declared as the official site for the

new national capital), little did Con Clark realise that, when the time came to

promote an international design competition for Australia’s new national

capital city in 1911, the incumbent Minister for Home Affairs would be the

‘legendary’ King O’Malley, an extroverted member of the House of

Representatives, representing a Tasmanian constituency—and an American.

O’Malley was supposed to be Canadian, but his political colleagues knew the

truth of his background. Both of these facts would not have harmed Con’s

prospects when he was chosen, in February 1912, as the proactive, informed

secretary to the competition’s judging committee.[43]

It is probable that Con Clark was more familiar

with contemporary town planning and architectural trends—better qualified than

the three judges to assess the hundred-odd serious, professional entries in the

competition. It is virtually certain that he was aware of the origins of the 23

American entries, including number 29 from a design dream team from Chicago,

Walter and Marion Griffin.

The 2013 Centenary year of the national capital

was, by any reasonable assessment, a community triumph. Yet Robyn Archer, the

Centenary’s Creative Director, was right in saying that the franking of such a

great year would come after, in the range of legacy projects that expand on

Canberra’s foundation story. The unlikely threads that link the city to Andrew

Inglis Clark, Moncure Conway and Conway Clark deserve a prominent place in the

burgeoning narrative.

[1] Moncure Daniel Conway, My Pilgrimage

to the Wise Men of the East, Archibald Constable & Co., London,

1906, p. 80.

[2] ibid., pp. 80–1.

[3] Moncure Conway to Andrew Inglis Clark, 28 May 1884, A.I.

Clark papers, University of Tasmania Library—Special and Rare Materials

Collection, C4/C28–36 (hereafter referenced as Clark papers). Chapters IV and V

of My Pilgrimage to the Wise Men of the East (pp.

70–103) detailing the months in Australia, provide some engaging reading.

Conway is a keen observer. His comments on the Melbourne Cup, more than a

decade before Mark Twain’s famous remarks about the same race, deserve their

own place in Australian sport literature (see pp. 74–5 of this volume).

[4] Andrew Inglis Clark, ‘The future of the Australian

Commonwealth: a province or a nation?’, in Marcus Haward and James Warden

(eds), An Australian Democrat: The Life, Work and

Consequences of Andrew Inglis Clark, Centre for Tasmanian Historical

Studies, University of Tasmania, Hobart, 1995, pp. 213–14.

[5] See Alex C. McLaren, Practical

Visionaries—Three Generations of the Inglis Clark Family in Tasmania and Beyond,

Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies, Hobart, 2004, p. 162.

[6] See Alex C. McLaren, ‘Andrew Inglis Clark’s family and

Scottish background’, in Haward and Warden, op. cit., p. 1.

[7] See Frank Neasey, ‘Andrew Inglis Clark and Australian

federation’, Papers on Parliament, no. 13, November

1991, pp. 83–4.

[8] A.J. Taylor, ‘Andrew Inglis Clark (1848–1907), an

Australian Jefferson’, in McLaren, Practical Visionaries,

op. cit., p. 96.

[9] The Mercury (Hobart), 15 July

1878, p. 2; John M. Williams, ‘ “With eyes open”: Andrew Inglis Clark and our

republican tradition’, Federal Law Review, vol. 23,

1995, p. 155.

[10] Richard Ely, ‘The tyranny and amenity of distance: the

religious liberalism of Andrew Inglis Clark’, in Haward and Warden, op. cit.,

p. 102.

[11] Quoted in Ely, op. cit., p. 106.

[12] Andrew Inglis Clark, ‘Prelude’, The

Quadrilateral—Moral, Social, Scientific and Artistic, vol. 1, no. 1,

1874, p. 2.

[13] ‘The Teaching of Emerson’, Quadrilateral,

vol. 1, no. 11–12, 1874, p. 255 (page incorrectly numbered—it should be p.

245).

[14] ‘Walt Whitman’, Quadrilateral,

vol. 1, no. 7, pp. 163–4.

[15] See McLaren, Practical Visionaries,

op. cit., p. 103.

[16] See Conway, My Pilgrimage, op.

cit., p. 8.

[17] Paul Collins, The Trouble With Tom—The

Strange Afterlife and Times of Thomas Paine, Bloomsbury, London, 2005,

p. 260.

[18] Moncure Daniel Conway, ‘Dedication and Preface’, Autobiography—Memories and Experiences of Moncure Daniel Conway,

vol. 1, Houghton, Mifflin and Company (The Riverside

Press, Cambridge), Boston and New York, 1904, p. vi.

[19] ‘Mr Moncure Conway’, Launceston

Examiner, 20 October 1883, p. 3.

[20] See John Keane, Tom Paine—A Political

Life, Bloomsbury, London, 1995, p. 393.

[21] See, for example, ‘Mr Moncure Conway’, Launceston Examiner, 20 October 1883, p. 3; Editorial, The Mercury (Hobart), 12 November

1883, p. 2; Letter to the Editor, ‘Mr Moncure Conway’, The

Mercury (Hobart), 17 November 1883, p. 2.

[22] See Conway, Autobiography, op.

cit., vol. 2, p. 416.

[23] Conway, My Pilgrimage, op.

cit., p. 74.

[24] Ralph Waldo Emerson, ‘Nature’ (1836) in Larzer Ziff

(ed.), Ralph Waldo Emerson—Selected Essays, Penguin

Books, New York, p. 35.

[25] ‘Her Majesty the Queen, as regarded by her subjects’, Evening News (Sydney), 26 September 1883, p. 7.

[26] ‘Mr Moncure Conway at the Tasmanian Hall’, The Mercury (Hobart), 27 October 1883, p. 2.

[27] ‘Mr Moncure Conway’s lectures—Woman and evolution’, The Mercury (Hobart), 31 October 1883, p. 3. See also ‘Mr

Moncure Conway’s lectures—Development and arrest in religion’, The Mercury (Hobart), 1 November 1883, p. 3.

[28] ibid.; ‘Mr Moncure Conway’s lectures—Toleration and the

martyrdom of thought’, The Mercury (Hobart), 2

November 1883, p. 3.

[29] ‘Mr Moncure Conway at Hobart’, Launceston

Examiner, 2 November 1883, p. 2.

[30] Moncure Conway to Andrew Inglis Clark, 25 November 1883,

Clark papers, C4/C28–36.

[31] ibid., 23 November 1883.

[32] Andrew Inglis Clark to Moncure Conway, 26 August 1899,

Moncure Daniel Conway papers, Rare Books and Manuscripts, Butler Library,

Columbia University, MS#0277.

[33] Moncure Conway to Andrew Inglis Clark, 28 May 1884, Clark

papers, C4/C28–36.

[34] John Reynolds, ‘A.I. Clark’s American sympathies and his

influence on Australian federation’, Australian Law Journal,

vol. 32, July 1958, p. 63.

[35] See Conway, My Pilgrimage, op.

cit., chapter X, pp. 195–214.

[36] Andrew Inglis Clark, ‘A critical approach to religion’,

quoted in Ely, op. cit., p. 115.

[37] Andrew Inglis Clark, ‘The evolution of the spirit’,

quoted in Ely, op. cit., p. 104.

[38] Reynolds, op. cit., p. 63.

[39] Richard S. Kennedy, Dreams in the Mirror: A Biography of E. E. Cummings, Liveright Publishing Corporation,

New York, 1980, p. 14.

[40] Conway Clark to Andrew Inglis Clark, 5 August 1905, Clark

papers, C4/C2–8.

[41] ibid., 21 July 1907.

[42] ibid., 9 September 1905.

[43] See ‘The most beautiful city’, The

Sydney Morning Herald, 27 May 1912, p. 8.

Prev | Contents | Next