Rosemary Laing

It was Harry Evans who first introduced me to Sir Richard Chaffey Baker—or 'Dickie' Baker as he fondly called him—the first President of the Australian Senate. Baker, though a native-born South Australian, had been educated at Eton, Cambridge and Lincoln's Inn, but had gone on to be an influential delegate at the constitutional conventions of the 1890s, bucking the standard colonial obeisance to all things Westminster. Like Tasmanian Andrew Inglis Clark and a few others, Baker questioned the very rationale of the theory of responsible government while promoting something rather more republican in character, though always under the British Crown.1

When the Senate Department's major Centenary of Federation project, the four-volume Biographical Dictionary of the Australian Senate, began to get off the ground in the early 1990s under the indefatigable editorship of Ann Millar, four sample entries were prepared to illustrate how the project could be done and what the entries would look like. An entry on Baker, researched and written by Dr Margot Kerley, was one of those four pilot entries. Perhaps it was a strategic choice given Harry Evans' great interest in the subject, but Harry needed little convincing that this was a worthwhile contribution to the history of federation and he remained the dictionary's strongest supporter, particularly at Senate estimates. Harry also read all entries, continuing to do so even after retiring, bringing to the task his great critical faculties and his unrivalled knowledge of Australian political history. He saved us from untold howlers. More notably, he contributed three magisterial introductions to the first three volumes published while he was Clerk, providing an historical overview of the periods covered by each volume.

As retirement drew closer, Harry would sometimes talk about pursuing a full-length biography of Baker as a retirement project. Sadly, it was not to be but he had planted the seed of an idea. So this paper represents some first steps towards realising that objective on his behalf. It provides an opportunity to express my gratitude to Harry Evans not only for everything he taught me but for contributing to keeping me out of trouble in my own retirement. I suspect our approaches would have differed quite markedly, but one of the joys of working with Harry was his tolerance of different approaches. The Journals of the Senate aside, he rarely insisted that something be done his way and only his way.

In his introduction to the first volume of the Biographical Dictionary, Harry singled out Baker for his dogged but unsuccessful attempts during the conventions 'to steer the Constitution away from the cabinet system of government…whereby the executive power is exercised by ministers dependent on the support of the lower house of the Parliament alone'. Baker favoured the Swiss style of federal government with a separately constituted executive government 'no less accountable to one House than the other'.2 Although he lost that battle, he was determined that the Senate should strike out on its own to interpret its constitutional role free of unnecessary dependence on British models and traditions, all this despite his quintessentially British education.

Although deeply conservative, Baker was a nationalist who did not regard what Harry Evans described as the 'Westminster cringe' as an essential element of his conservatism.3 Above all, Baker was a federalist. His strong belief that federation was in the interests of all the colonies overcame his adherence to a particular model of federalism and allowed him to live with the resulting compromise. He was sufficiently original and flexible in his thinking to cleave to a new, peculiarly Australian model of governance in which a Senate, representing the people of the states, was a critical element. Before there was a nation, he had a deep sense of the national interest, largely founded on the economic benefits to the colonies of free trade between them and of a uniform tariff. And we must recall that Baker had a significant economic stake in the national interest, with pastoral and mining interests across several states.4 He was a capitalist federalist. As a wealthy man and a South Australian to boot, he was fond of pointing out that he was the first native-born South Australian to achieve numerous offices.5

At an operational level, as President, Baker steered the Senate's standing orders, or operating rules, sufficiently away from the House of Commons bias of the Senate's first Clerk, Edwin Gordon Blackmore, to equip this bold new institution to exercise unprecedented powers in the world of parliamentary government. He was able to do this because he brought to the role a huge reputation as a highly effective and even-handed chairman from his background as a long-serving President of the South Australian Legislative Council but, more importantly, as the Chairman of Committees of the 1897–98 Australasian Federal Convention which meant he conducted the detailed stages of the convention, as opposed to the debates in plenary. In that role he wrangled hundreds of amendments that had come out of the colonial parliaments' earlier deliberations on the bill.6 At the end of the arduous final session of the convention in Melbourne, when the details of the Constitution Bill had been exhaustively considered, convention leader and future Prime Minister Edmund Barton commended Baker's organisation of amendments in a very complex committee stage, and for ensuring all received a fair hearing and a vote. Barton noted the tact, skill and judgment with which Baker ran the proceedings, in addition to his devotion to the cause of federation. Delegates might also have fallen off their chairs to hear Convention President, Baker's deadly enemy, Charles Cameron Kingston, claim that it had been 'an undoubted pleasure to co-operate with Sir Richard Baker in the discharge of the business of this Convention'.7 And when I say 'deadly', barely six years earlier, Kingston had challenged Baker to a duel, with pistols. Was he finally learning diplomacy or did he actually mean it?

But it was one thing to be a talented chairman. Baker also contributed substance. Through his studies, readings and experience, he brought well-founded ideas about governance to each of his roles as a member of parliament, convention delegate and presiding officer. In particular, as Senate President, he fought to ensure that the Senate's significant financial powers as envisaged by the Founders remained—or at the very least, a significant proportion of them, specifically those representing the smaller colonies of South Australia, Western Australia, Tasmania and, to a lesser extent, Queensland. He did not always win. To Baker's mind, strong financial powers were the key to respect for a Senate that was virtually co-equal in power to the House of Representatives, as befitted the body charged with representing the federal elements of the Constitution. In the short to medium term, one would have to conclude that he failed but the foundations he laid remained available for rediscovery when interest in the Senate and what it could do revived in the second half of the twentieth century. For this reason alone, Sir Richard Baker is someone we should know a lot more about.

While Dick Baker himself did not leave a great deal in the way of personal papers, there is a wealth of source material about his life and times.8 Most of the big federation names knew him well.9

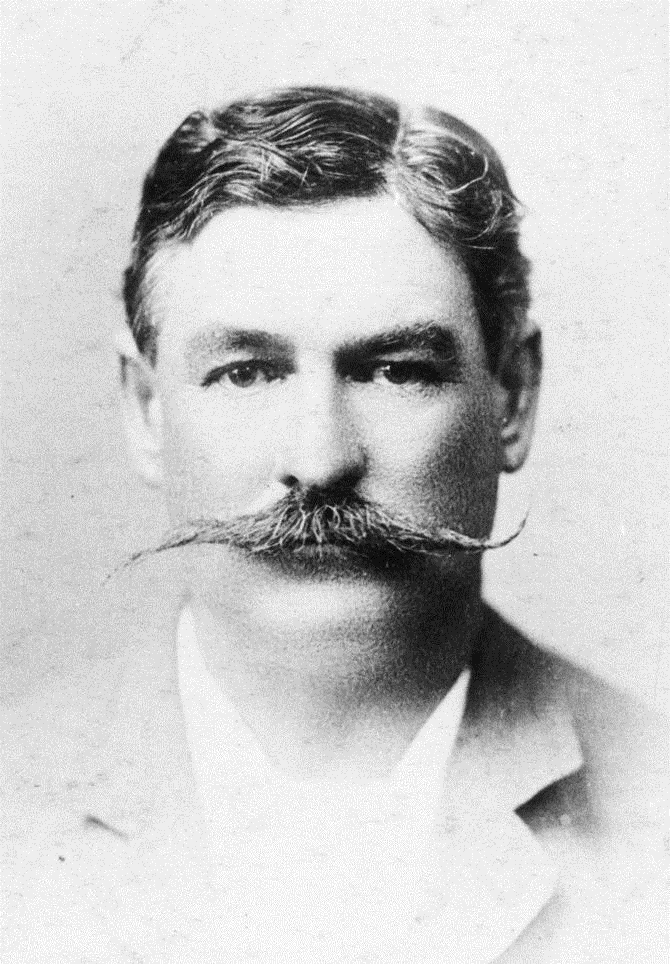

Richard Chaffey Baker, c. 1860. State Library of South Australia (SLSA): B 3692

There are several portraits of Baker, both in oils and in photographs, but as Mark McKenna has noted,10 we lack much in the way of pen portraits. Alfred Deakin, who described many of his contemporaries in arresting physical detail, avoids describing Baker's appearance and focuses instead on his knowledge of all matters federal, knowledge which Deakin assessed as 'in advance of all his colleagues'. We might wonder whether Deakin deliberately avoided mentioning one of Baker's most prominent features—his alarmingly excessive waxed mustachios. And he remained attached to them for decades!

There are, however, some other glimpses. An earlier South Australian colleague,

W.B. Rounsevell, in 1915 recalled descriptions of the members of the Colton cabinet of 1884–85 as the 'Ministry of the Talents' or the 'Ministry of the Giants'. Apart from Chief Secretary Colton and Treasurer Rounsevell, the cabinet included Attorney-General Kingston, Jenkin Coles as Commissioner of Crown Lands and Immigration, Thomas Playford as Commissioner of Public Works and Richard Chaffey Baker as Minister of Justice and Education. All were around 6 foot tall except for Playford who was 6 foot 4 inches and Baker who, at 'about' 5 foot 9 inches, was 'the smallest man of the lot' and 'a clever, smart, subtle fellow' who never got on well with Kingston.11 There are also some character sketches, including from George Pearce, a Labor member of the first Senate, Minister for Defence during the First World War and still the record holder for the longest-serving senator of all time. Having commended Baker's impartiality and fairness in the chair, he observed that Baker 'had a very peppery temper and did not suffer bores gladly'. He goes on to give an example of a very obsequious senator who craved the President's indulgence to make a few observations on a matter and was told sharply by Baker not to apologise to the President for his presence. He was not responsible—it was the electors of his state!12 In the chair, Baker mastered the acerbic put-down well.

Dick Baker was born in June 1841. He was from a large family, the eldest son of twelve children born to John and Isabella Baker. His father, John Baker, was himself the son of an earlier Richard Chaffey Baker. Born in Somerset, John migrated at 21 to northern Tasmania, with a brother and sister, and worked as a shipping clerk before starting a shipping business. He married the daughter of a wealthy Scottish businessman, George Allan, in Launceston in 1838 and the same year left for South Australia, his wife and siblings following in 1839. His mother and other siblings also emigrated to South Australia.

Initially, John Baker was in the business of shipping sheep and horses from Tasmania to South Australia but he soon became established in stock and land sales, with some whaling on the side. He formed the Adelaide Auction Company with partners, acquired numerous rural holdings and a substantial house in Brougham Place, on the north side of the Torrens River, and built 'Morialta' at Norton Summit near Magill in the Adelaide Hills a few years later. Neighbours there included Dr and Mrs Penfold in 'Grange Cottage'. With substantial business and civic influence, John was known as the 'King of Morialta'. He was a member, trustee or chairman of any Adelaide institution that mattered, as well as a benefactor of the Anglican Church. John Baker was also a politician, appointed to the Legislative Council prior to self-government and elected thereafter. He was South Australia's second Premier and although he was in office for only eleven days, during that time he negotiated what became known as the Compact of 1857. This was the financial understanding between the House of Assembly and the Legislative Council that would later become the model for the Compromise of 1891 and therefore the key to Australian federation and the financial powers of the Senate relative to the House of Representatives. In short, John Baker was a formidable man to have as a father, although he died at only 59.13 He was the model of the capitalist politician.

‘Morialta’ c. 1890–1900. SLSA: PRG 38/2/1

On Boxing Day 1855, aged 13, young Dick Baker boarded the sailing ship Victoria (524 tons), under Captain Forss, on a voyage to England and school at Eton. His father had entrusted him to the care of Mrs John Morphett who was travelling to England with her 10 children, including her eldest son, John Cummins Morphett. John will reappear later in this story.

We know some things about the voyage from Morphett family records, compiled by George Cummins Morphett, son of the aforementioned John Cummins Morphett.14 A rather more charming version of the story was passed down by the Morphett's third daughter Ada, aged 12 at the time of the voyage, to her granddaughter, Geraldine Pederson-Krag, who wrote it up as a children's adventure story, published in England in 1940 as All Aboard for England! and in America in 1941 as The Melforts Go to Sea.15 Parading as thinly disguised members of the Morphett family, the numerous Melfort children make preparations to sail for England in the yearly packet, the Regina, under Captain Bond, where it is expected that the boys might spend a few years at schools (although they don't).16 Reflecting contemporary rates of infant mortality, the two youngest children are known only as the Old Baby and the New Baby.17 Jack Melfort, aged 11, is delighted when his mother informs him that Dick Butler is to travel with the family to London. Indeed, 'Jack could not have been more delighted if he had been told that Robinson Crusoe himself was to be his fellow traveller'. Robinson Crusoe was one of his favourite heroes. The stage is set for a boys' own adventure story.

Two years older than Jack, Dick had 'a lively reputation for fun and deeds of daring'.18 Jack imagines swimming and climbing the rigging with Dick but things do not begin well. The boys had not previously met. Having just parted tearfully from his own father who exhorts him to be kind to Dick because he does not have any of his family with him, Jack first sees Dick 'leaning pensively over the stern', 'a slender figure in immaculate nankeens and a black straw hat'. Jack makes a casually adult remark about the weather that he has heard his father make but Dick utters a queer sound and waves him away furiously with his hat. When Dick fails to join the Melforts for nursery tea, Jack assesses him as 'too grand or something' and resolves to hate him but later, seeing Dick's blotched face, the penny drops and, after some mandatory fisticuffs in their tiny four-berth cabin, the two boys become firm friends, as boys do in such tales.

While the story's focus is largely on Jack and Ada Melfort, Dick's distinguishing features are his wit and the map that his father has given him to mark the position of undiscovered islands and ships and other interesting things.19 The map becomes an absorbing occupation as the boys decide what to include. At Dick's suggestion, they settle on a system of description with useful information for travellers. Given the boys' limited horizons, useful information comprises what to wear to describe latitude and what to eat, describing longitude. First they pass through the Calico latitudes, then into the Red Flannel latitudes, the All on by Night or Quick Bed latitudes and finally the All on by Day latitudes, the last three collectively described as the Scratchy latitudes.

As it becomes colder, and whales and icebergs appear, the captain surprises everyone by confirming that they are indeed sailing east rather than west and will round Cape Horn rather than the Cape of Good Hope. Of course, this turns out to be as perilous as it sounds. Food and water supplies rapidly dwindle from the Plentiful Longitudes through the Cold Meat, Potted Meat, and Jam and Tinned Fruit Longitudes respectively. As the boys await imminent shipwreck rounding the Horn, they polish off the last of the Plum Cake and Pudding from those longitudes before the ship breaks free of an iceberg and they turn north, enduring days of Mariners' Fare before entering the Very Little and Almost Nothing latitudes. Their first sight of land is Pernambuco at the eastern tip of Brazil, but the yellow fever flag is up and they must go further north to Olinda to re-provision. Mama Melfort, her letters of credit for Western Australia and the Cape of Good Hope utterly useless in these heathen lands, dons her finest clothes and takes her jewellery ashore to pawn to buy food for the little ones, the captain having swindled them again in loading poor quality stuff masked with a top layer of good stuff, just as he had done out of Adelaide. Adventures continue—the New Baby is briefly kidnapped by savages who board the ship before the clever Melfort children outwit them. Finally, they dock in London and Dick Butler is met by an uncle and aunt and carried away in a carriage after thanking the Melforts for their kindness.

It is a charming tale, enriched by the author's own childhood experiences of long sea voyages. There is no doubt some semblance of truth in the basic threads of the plot. Wealthier South Australian settlers, in particular, did decamp to the 'Motherland' for shorter or longer periods. Children were sent 'Home' to be educated, particularly to Oxford or Cambridge though less commonly to English schools. The voyage, by sailing ship, was long and perilous, and the Circle Route around the Horn saw ships venturing far into Antarctic latitudes to catch the strong westerlies. There are stories of settlers' babies being kidnapped in South American ports en route to South Australia, and subsequently rescued. My own feeling is that Dick's map and the types of information he populated it with are too good to be inventions. They strike an authentic note and reveal a character with a systematizing mind and a facility for structure and organisation, a mind that would later turn to constitutional and institutional design and operation, including the rationale of standing orders.

After four years at Eton, Dick went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1860, and was admitted to Lincoln's Inn in 1861, graduating and being admitted to the Bar in 1864.20 He then came straight home.

Little more than twelve months after his return to Australia, Dick married Katherine Edith Colley at St Peters, Glenelg, in a double wedding ceremony with Katherine's sister, Isabella, and grazier, William Reid. About ten months later, their first son, John Richard Baker, arrived in October 1866 and their second son, Robert Colley Baker, arrived in May 1879 after an unexplained gap of nearly 13 years. Two years later came a third son, George Chaffey Baker, who did not survive and, finally, a daughter, Adelaide Edith Baker in April 1884.21 Addie, according to the Governor's wife Audrey Tennyson, was charming and amusing and much given to fashion,22 but the younger children did not marry and there were never any grandchildren. Unlike the Morphetts, the Baker line now has no family story keepers of direct descent.

By 1868, at the age of 26, Dick Baker was a member of the House of Assembly for the district of Barossa.23 He was appointed Attorney-General in John Hart's third ministry but resigned to look after his father's affairs when he sickened in 1871, before his death the following year.

Baker suffered his only electoral defeat in May 1875, when standing for his old seat of Barossa, but was elected to the Legislative Council in 1877 and was from then on a member of parliament continuously till his retirement from the Senate at the end of his term in 1906. In the 1877 campaign material, Dick's native-born status was highlighted, along with his late father's reputation, his previous experience as an MP and, interestingly in light of his later path, a perception of non-partisanship. A piece of doggerel published at election time referred to 'that clever young fellow, Dick Baker…Our longheaded, strongheaded Baker; A chip from the stock Of a famous old block…Our plain-dealing, right-feeling Baker…Straightforward in action, And free from all faction, Few members did better than Baker'.24

Notwithstanding periods of ministerial service,25 Baker apparently preferred the freedom of being an individual member of the Legislative Council, a role possibly more compatible with his extensive business interests. From time to time he wrote opinion pieces for the press, including on industrial relations, individual taxation, socialism and, of course, federation. Given his views and his advocacy for federation from an early date, his choice as a delegate to the 1891 National Australasian Federal Convention in Sydney was not surprising and he took to the conference a comprehensive manual for the delegates on federal constitutions with comparative material about the USA, Canada and Switzerland. His contribution to the conference and the other delegates' use of the manual has been analysed by South Australian historian, Rob Van den Hoorn.26 Although not heavily cited directly, the manual's influence on delegates' thinking is apparent from many references to information in it. The manual was one of only four pieces specifically prepared for the convention. The others were the draft constitutions prepared by Andrew Inglis Clark and Charles Cameron Kingston, and a collection of extracts and documents prepared by Tasmanian, Thomas C. Just, under the title, 'Leading Facts Connected with Federation', primarily for the Tasmanian delegates.27 The manual was unique as a constitutional text.

Baker's status changed at the end of 1893 when he succeeded Sir Henry Ayers (of Ayers Rock fame) as President of the Legislative Council. Sir Henry, among many other things, was the father-in-law of his childhood shipmate, Ada Morphett.

It is worth contemplating what led Baker to the chair in the first place.28 He had held ministerial office and seen the revolving door of colonial politics—his refusal of office on more than one occasion perhaps indicates that his interests lay elsewhere. His father had been Premier but there was no sign that Dick sought to emulate him. He was, however, surrounded by old family friends and relations who had earned great respect as presiding officers over lengthy terms in office. These included Sir John Morphett, Sir James Hurtle Fisher (Morphett's father-in-law) and his own brother-in-law, Sir Robert Dalrymple Ross, who died in office as Speaker in December 1887. As President of the Council, Baker had a chance to secure his status and reputation as a leading man in South Australia, particularly after he won a long-running battle to secure an appropriate place for the presiding officers in the South Australian order of precedence.29 It is unlikely that he foresaw the long term in government of his enemy Kingston and the consequent lack of opportunity for any partisan political ambitions of his own. It may also be that he enjoyed the work and it gave him time to devote to contemplating more abstract intellectual and political questions that interested him greatly. Undoubtedly, after a slightly rocky start, he developed a facility for chairing that allowed him to put partisan considerations aside and ensure fair play in proceedings.30

Baker's reputation as an impartial and fair chair was confirmed and brought to national attention at the 1897–98 convention where Quick and Garran report that he took the chair in committee at the Adelaide session 'amidst cheers'.31 It was clear soon after the convention that he resolved to seek the Senate presidency, but the situation was not without some irony, given the shenanigans over where the first meeting of the convention would be held and who would chair it, all well described by Alfred Deakin.32 Adelaide won the prize and Kingston won the presidency but, in the event, both Kingston and Baker were largely sidelined by their respective roles as President and Chairman of Committees. Baker's scheme to keep Kingston off the drafting committee was as dastardly as his mustachios. Thus, ego, mutual hatred and bloody-mindedness denied the convention the unrestricted contribution of two of its most expert members and foremost proponents of federation.33

As we have seen, Baker's preferred federal model failed to gain support and the Senate he strove to create to protect the interests of the smaller states was not as strong as he had hoped. The majority did not agree with Baker's views on responsible government and, true to the prediction in his opening speech to the Adelaide session,34 responsible government and its conventions would come to exercise disproportionate influence in the careful federal balance. For all this, Baker's enthusiasm for federation did not wane and, despite health problems associated with the kidney disease that would eventually kill him, Baker remained keen to become the Senate's first President.

Baker's journey towards the Senate was echoed by that of another South Australian, Edwin Gordon Blackmore, who was appointed as the first Clerk of the Senate. In a comprehensive account of the opening of the first Parliament and associated revelries, Audrey Tennyson captured the excitement of having so many South Australians in influential positions in the new Parliament—Kingston in cabinet, Holder and Baker as presiding officers and Blackmore as Clerk of the Senate.35

Blackmore, also of Somerset origin like the Bakers, had arrived in South Australia via New Zealand where his medical father had taken the family to join a brother who was secretary to Governor Grey. Blackmore saw combat in the Maori Wars in 1863 and 1864 before leaving to join another brother in South Australia in parliamentary service. He was appointed parliamentary librarian in 1864 where he befriended the poet Adam Lindsay Gordon, an amateur jockey and one-time member of the House of Assembly, who later sold him a jumps horse.36

In 1869 Blackmore became Clerk-Assistant (or second in charge) in the House of Assembly and Clerk in 1886. The following year he was promoted to the more senior post of Clerk of the Legislative Council and Clerk of the Parliaments. In this post, he also clerked the 1897–98 constitutional convention, which set him up as one of the frontrunners for the post of Clerk of the Senate in 1901. His papers from the convention are now in the National Archives of Australia. They are meticulously well-organised, demonstrating many good clerkly habits that are still discernible in Senate practices.

While Dick Baker was serving in the House of Assembly from 1868 to 1871, Blackmore was in the parliamentary library, then Clerk-Assistant in the Assembly. When Baker served in the Legislative Council from 1877 to 1900, Blackmore was a senior parliamentary officer, becoming Clerk of the Council in 1887 and working directly with Baker as President from 1893.

There was also another familiar face on the Council staff at this time. Blackmore's second in charge from 1888 was John Cummins Morphett, Dick's cabin mate from the voyage of the Victoria to Great Britain in 1856, that eleven-year-old boy depicted as Jack Melfort in All Aboard for England!37 When Blackmore was granted furlough by the Legislative Council in 1900 so that he could recover from the rigours of the convention and travel 'Home' to hobnob with all his House of Commons and academic connections, John Cummins Morphett acted as Clerk during Dick Baker's last year as Council President. One wonders whether they recalled their earlier adventures and Dick's famous map during no doubt earnest discussions over the application of standing orders and the coming federation.

Blackmore did not quite share the social status of the Bakers, but he was nonetheless a significant man about town with many important connections. He was a member of the Adelaide Hunt Club, including as its master and secretary, a member of the Church of England synod, a member of the church's Aboriginal mission at Poonindie, a governor of St Peter's College, and a coach and official of the Adelaide Rowing Club. He married the daughter of Archdeacon G.H. Farr, headmaster of St Peter's. He also lectured in history at the University of Adelaide. In 1900, he wrote a book about the establishment of the South Australian Bushmen's Corps, the organising committee of which he had been a member.38

His history as a parliamentary officer was enhanced by his decision to embark on a series of parliamentary texts, crowned by his production of a manual of practice for the House of Assembly, and one for the Legislative Council. He was the only person in Australia doing this for the time being, and his string of titles, which included a series of several books of the rulings of the Speakers of the House of Commons in London, set him apart from the usual run of parliamentary officers from the other colonies.39

It seems, however, that Blackmore's ambitions to become the foremost parliamentary officer of the new nation were not widely shared. In Melbourne, in particular, where the Clerk of the Parliaments, G.H. Jenkins, saw Blackmore's ambitions as beyond the scope of his duties as the Clerk of Parliaments of a minor colony, Blackmore's claims to be the first of his cohort went beyond what was appropriate. For Jenkins, Blackmore was head of a service with 'the same importance as a parish council, no more than the Board of Works'. He was someone who 'wrote a few useless compilations of Imperial Speaker's decisions for the sake of notoriety!' 'Those paltry collections of precedents are only a low advertising dodge!'40 Yet it was Blackmore's clerkship of the 1897–98 convention that brought him to a national audience.

I have yet to find any correspondence between Blackmore and Baker about Blackmore's quest to be Clerk of the Senate. It is almost as if Blackmore had no idea that Baker would become his President, despite the latter's well-known ambitions.41 But Blackmore lobbied others. A.J. Peacock of Victoria, who showed his letters to the Victorian Clerk, Jenkins, was quite outraged that Blackmore appeared to be asking him for a testimonial. Blackmore then wrote further letters to Peacock to withdraw any such suggestion that he may have made.42 Once it appeared that Barton would be the new Prime Minister, Blackmore was on the front foot. He was working out of Sydney well before he was appointed as Clerk of the Senate on 1 April 1901. Barton used him to write the first standing orders for the Senate and the House of Representatives while Jenkins, first acting Clerk of the House, arranged the opening ceremonies.43 Meanwhile, Baker was gentlemanly enough to hold on to his letter of resignation until Blackmore's appointment as the first Clerk of the Senate came through officially.44

When it came to the election of the first President of the Senate, the Senate's first debate was about how it should be done. Senators eventually settled on a system whereby the first person to gain a majority of votes would be elected President. It took only one ballot to elect Baker as first President. He was the third candidate nominated after Senators Zeal (Protectionist) and Sargood (Free Trade), both Victorians, but he stole the show with 21 votes on the first ballot, with Sargood getting 12 and Zeal getting three.45 In fact, Baker was a rare President, not being of the governing party (although he had publicly committed to support Barton's protectionist ministry). He was a free trader through and through, but his ability to step back from his partisan political beliefs had been shown before and his reputation as an excellent chair was still in people's minds. He clearly had the confidence of his colleagues despite the Victorian rivals.

On the other hand, Blackmore's clerkly efforts were not overwhelmingly appreciated. The Senate rejected a motion to adopt his draft standing orders and instead opted to use those of the South Australian House of Assembly that had been used at the 1897–98 convention. A Standing Orders Committee then worked up its own set.46

Draft standing orders sat on the table for a couple of years till they were debated in June and August 1903. Between these two periods of debate, another Standing Orders Committee report was tabled that revived the old idea of a standing order that referred to the House of Commons in Westminster as the source of all other parliamentary lore. It was not a standing order that the President favoured and was, in fact, inimical to his object.47 There is more digging to do but it seems to me that this report was perhaps the work of a Senate Clerk about to lose one of his last important battles with his President.

All of Blackmore's old publications in South Australia, his several volumes of House of Commons Speaker's rulings and his manuals for the operation of both Houses had been predicated on a very close resemblance to the way that things operated in the House of Commons. On the other hand, Baker had a completely different view of the role of the Senate in the future operation of the Australian Parliament. It was not a copy of the House of Commons that Baker was pursuing. It was a new federal structure that brought together the representatives of the states in a new kind of parliament whose sole difference from the powers of the House of Representatives was to be specified only in section 53 of the Constitution as it now was.48 This was the only sense in which the powers of the two houses differed. So when Baker embarked on the arguments about the standing orders, it was not about yet another different type of colonial upper house—it was about a kind of second chamber that would be quite different to any kind of chamber that had been established before.

Baker during his time as President of the Senate

There are many examples of the kinds of standing orders where Baker attempted to excise layers of meaning that had accrued over centuries in Great Britain. Although undoubtedly a conservative, Baker had no love for meaningless ritual. An example of his minimalism is the kind of statement a newly elected President might make to a Governor-General when presented to that officer after his election. The usual kind of thing that was claimed from a head of state, be it a governor in the colonial parliaments or the Queen in Great Britain, was a summation of what the House of Commons had been claiming since the mid-sixteenth century. It was a claim to 'their undoubted rights and privileges', and praying 'that the most favourable constructions may be put upon all their proceedings'. This was what Blackmore's draft had had, and if senators took any notice of the minutes for the first day of the new Parliament in 1901, this is apparently what President Baker had claimed from the Governor-General. Whether that happened or not was a moot point. When the relevant standing order was debated in 1903, the new terms were: '[h]e shall, in the name and on behalf of the Senate, claim the right of free and direct access and communication with His Excellency'. Senator Best wanted to amend it to restore the old 'rights and privileges' approach but the President was blunt in his assessment:

The old words were departed from because they are a survival of the procedure which has come down to us from the time of the Tudors and Stuarts, when the Speaker of the House of Commons claimed from the Crown certain rights and privileges.

And Baker knew about Tudor Speakers. He was descended from Henry VIII's last Speaker, Sir John Baker, of Sissinghurst, Kent, where the Baker coat of arms can still be seen carved into the gatehouse. Interestingly, it shares various devices, including three swans, with Dick Baker's crest.

Baker continued:

The use of the words has been continued by all Parliaments down to the present time, though they now involve the ridiculous absurdity of the President or the Speaker claiming from the Crown rights which the Crown cannot grant, and the Crown solemnly granting those rights. Is it not time we stopped that? What right has the Crown to abrogate the common law? Under section 49 of the Constitution we have all the powers, immunities and privileges of the British House of Commons, and it is under that section of our Constitution that we are exempt from the law of libel and from arrest while attending Parliament. It seems to me that we should adapt our procedure to existing circumstances, and we should not ask His Excellency to grant us that which he cannot grant, and leave him to pretend to do that which we know he cannot do.49

Senator Best then asked, well, why do we have anything at all? And so the current form was arrived at which makes no mention at all of what the President says to the Governor-General on presentation. There is no need because all of the rights and privileges are provided in the Constitution. This is one of a number of examples where the old colonial standing orders were similarly updated.

So, what was the relationship between Baker and Blackmore? My view is that it probably worked best for Blackmore when he was Clerk of the Legislative Council, happily conferring with his friends in Westminster about precedents while Baker learned the ropes as a presiding officer.50 Baker, however, came to a much deeper understanding of the role of the Senate than Blackmore could ever emulate.

One other point is worth making and it is a personal one. When parliamentary officers moved to Melbourne to take up their posts, none of Blackmore's previous man about town activities in Adelaide translated to Melbourne. Maybe it was the death of his wife in 1901. Maybe his health was beginning to decline. In any case, his years in the Senate, particularly after he lost so comprehensively on the standing orders, were without any of the major publications that had made his name hitherto. Though having led the cohort of Australian clerks in the years leading up to federation, Blackmore's post federation career was relatively unspectacular.

For Dick Baker, however, his last years in the Senate were potentially his best, notwithstanding ill health that may have dogged them. In 1904 he wrote a memorandum on how the Senate might establish its procedural independence, entitled 'Remarks and Suggestions on the Standing Orders', which was tabled on 9 March 1904 and referred to the Standing Orders Committee.51 The paper was a response to the absence of an 'umbilical' standing order tying the practices of the Senate to those of the House of Commons. Baker held that 'in cases not specifically provided for we should gradually build up “rules, forms and practices” of our own, suited to our own conditions'. He suggested that the President should make rulings on the best procedure to adopt and, as later agreed by the Senate,52 that rulings should stand unless the Senate altered them. Each session, the President should report on previous rulings and identify anywhere the result was inconvenient, allowing the Senate to decide the matter.53

The President's first such report was tabled on 17 August 1905.54 All Presidents since then have added to the corpus of knowledge about interpreting the Senate's rules. It is a practice that is absolutely fundamental to the Senate's independence.

When Dick Baker died in 1911, he was thoroughly lauded as a 'great constitutionalist'. He did more than most to design an institution to represent the people of the states and to ensure that its early operation went as far as it possibly could in achieving its goal of equality amongst states, regardless of their population size. But there are many reasons why Baker has been forgotten. To summarise:

- he was a conservative member of parliament, not at all fashionable amongst the rediscovered radicals of the centenary of the federation era

- he did not hold much truck with pursuing a ministerial career and was not therefore seen as a leading light by those same historians

- he championed the Senate as a states house to represent the interests of the smaller states, never a popular cause

- as he foresaw, his vision of federation was soon overtaken by the dominance of responsible government in the political mix, a dominance that was exacerbated by global events starting in 1914

- as a parliamentarian rather than a politician, Baker's abiding interest in the structures of governance were nonetheless focussed on advancing the interests of businessmen such as himself, interests which for him were consonant with the national interest but which for many others became consonant with individualistic self-interest over national concerns. In short, he was a capitalist. Other political movements prospered to promote the kind of communal and socialist focus he would have abhorred.

Finally, without direct heirs, it is easy for his legacy to be lost. The challenge is now to revive it.

Question — Rosemary, thank you very much for a fascinating lecture. You did not really say much about what Baker's contemporaries, particularly other senators, said about him. Is that a completely separate area of inquiry?

Rosemary Laing — Yes, I suppose it is. I did not use material from his final debate or his obituary. I did mention, of course, George Pearce, who was a member of the first Senate and who wrote a book about his recollections of the era. Baker did have enemies and one of them was another South Australian senator, Josiah Symon, who seemed to fall out with everybody. He was another lawyer and a very pernickety person—I think he was actually Baker's mother's lawyer—and it got to the point where Symon would not communicate with Baker at all. So there must have been things about Baker that did get up people's noses, but for the most part he seemed to be highly regarded by his peers and very highly regarded as a chair. That is what they were interested in—getting a fair go from the chair—and he was highly, highly lauded.

Question — I would like to ask if I formed the wrong impression that Baker was not of a democratic sentiment, being relatively undemocratic and perhaps even 'un-republican'. How did this translate into his attitude towards the party system which was forming at that time?

Rosemary Laing — Baker had a very strong sense of the party system. To go to the point about democracy, I do not think he was undemocratic but I think he had a 'born to rule' attitude to life and felt people should keep their places. He hated socialism and he hated the idea of socialism, and in response to the first Labor members being elected to the South Australian Parliament he formed a new political party, the National Defence League. However, when he became President of the South Australian Legislative Council in 1893, he made a big point of stepping back from the activities of the party so that he could be seen to be impartial in the chair. So he is that balance between that man of principle in the chair but also a pretty down and dirty politician when he needed to be.

Question — In a sense, doesn't that explain why Baker has been erased from public recollection?

Rosemary Laing — Quite!

Question — As President he was neutral in his preoccupations, but after assuming the role did Baker make public speeches commenting on the issues of the day, for example on protection or free trade? Were these speeches reported in the press when he was running for re-election or are they totally lost?

Rosemary Laing — Well, Baker only served one term as a senator, but certainly the campaign material from earlier elections to the South Australian Legislative Council drew on all his experience in many forms. He continued to write pieces for the press, but I suppose his later contributions were more about federation and the idea of federation. He is interesting in that he was a free trader and the first government was not a free trade government. So he is one of the very few Senate Presidents who was not from the governing party and he seemed to have been elected on his merits as a chair rather than anything else. He had competition from Victorians for the chair but he was able to overcome them.

I think you are probably quite right that he stepped back from the politics. As President, he tried to take on more stately roles. For example, he was very proud to represent Australia at the Imperial Durbar in India in 1903 where Edward VII was proclaimed emperor of everywhere. Audrey Tennyson has a lovely bit about how many blouses young Addie Baker, who accompanied Baker in place of his wife, took for the occasion. But Baker was sort of a partisan nonpartisan if you get what I mean. He had it both ways.