Kim Dovey

Parliament House in Canberra is 30 years old this week. The lawns have been mowed to mark the occasion and the fence to keep the citizens off the hill is under construction (Figure 1). While it is customary on such occasions to avoid criticism of the celebrant and I could happily extoll the virtues of what is surely a masterfully composed building, I want to explore the relations of architecture to power, which requires that we put architecture in its place as part of a much larger assemblage. I have only once published a critique of this building and that was nearly 20 years ago in the book Framing Places.1 I will repeat some of that material here because not much has changed. This is a first point about this relationship of architecture to power—architecture has great inertia, it produces durable change. I will begin with a few general observations about these relations before returning to Parliament House with a gentle critique and a little birthday gift.

Figure 1: Parliament House at 30 (2018). Photographer: Kim Dovey

If power is a general capacity to get things done, then political power is but one dimension of this very strange concept that often seems to be everywhere yet nowhere. When we look at a place like Parliament House or Canberra as a whole then it would seem to be all about locating the centre of power in space. Yet another principle in understanding this relationship is that power often works by hiding itself in plain sight and in silence. Architecture and urban design frames space, both literally and symbolically. In the literal sense our lives take place within the clusters of rooms, buildings, streets and cities we inhabit. Our actions are enabled and constrained by walls, doors, rooms and corridors, by streets, fences, gates and guards. As a form of discourse, buildings and places also tell us stories, they construct narratives and mythologies. In each of these senses architecture frames the places of everyday life.

A frame is also a 'context' that we relegate to the 'taken for granted'. Like the frame of a painting or the binding of a book, architecture is often cast as necessary yet neutral to the life within. Most people, most of the time, take architecture for granted. This relegation of architecture and space to an unquestioned framework is the deepest linkage of built form to power. As Pierre Bourdieu puts it 'The most successful ideological effects are those that have no words, and ask no more than complicitous silence'.2 The more practices of power can be embedded in the framework of everyday life, the less questionable they become and the more effectively they can work.

When we think of political power we generally refer to the power of the state over its citizens. Here we must make the key distinction between power to and power over.3 The term 'power' derives from the Latin potere—'to be able', the capacity to achieve some end. Yet power in human affairs generally involves control 'over' others. This distinction between power to and power over, between power as capacity and as a relation, is fundamental. Power to is the original or ur-form of power, the capacity to act, empowerment. While less primary, power over is much more complex and incorporates a range of forms and practices such as force, coercion, manipulation, seduction and authority. These practices all have crucial connections to architecture and urbanism which I have explored elsewhere in relation to building types such as shopping malls, corporate towers, courthouses, housing enclaves and public space.4

Authority/legitimacy

'Authority' is a form of power over that is integrated with the institutional structures of governance and which relies on an unquestioned recognition and compliance. It is the most pervasive, reliable, productive and stable form of power, but it rests upon a base of legitimation.5 We recognise the authority of the state as legitimate only when it is seen to serve a larger public interest. The key linkage to architecture here is that authority becomes stabilised and legitimated through its symbols—the trappings of power. The nation state is not visible, it is what Ben Anderson calls an 'imagined community' that must be rendered visible through an iconography of buildings, maps and monuments, often represented on money and stamps, that affirm the story of the nation, enabling citizens to imagine what they cannot see.6 The anthropologist Clifford Geertz puts it well:

No matter how democratically the members of the elite are chosen…they justify their existence and order their actions in terms of a collection of stories, ceremonies, insignia, formalities and appurtenances…that mark the center as center and give what goes on there its aura of being not merely important but in some odd fashion connected with the way the world is built.7

When such narratives are embodied in architecture and urban design, the ways the world is built resonate with the ways the city is built to become part of the unquestioned framework of political life. If citizens take the state for granted then we enter into this 'silent complicity' and state authority is affirmed. It is common to conceive of the nation state as somehow timeless when it is a relatively modern institution that is mostly established by violence. Australia is one of the more democratic and just societies on the planet, yet it was founded by the violence of a British invasion, and the authority of the state thus established is based in part on forgetting that founding violence. Thus new mythologies such as the Anzac myth are born to legitimate the nation state and rendered permanent in vistas, buildings and monuments.

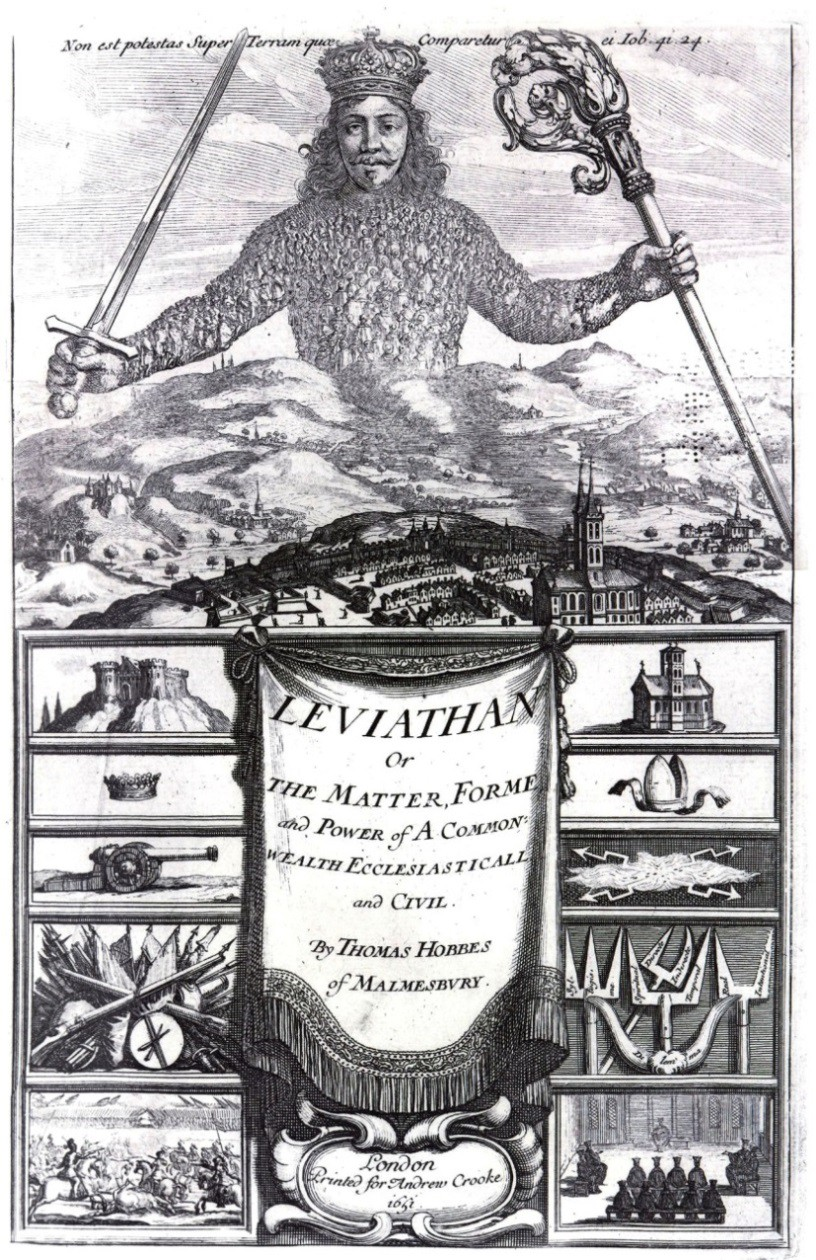

Figure 2: Frontispiece to Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, 1651. Source: Creative Commons 10

In 1651 Thomas Hobbes famously observed that the state is our defence against the natural order of 'dog eat dog'. State power involves a contract between the state and its citizens—we surrender our autonomy, our power to, and we grant the state power over us in order to avoid a life that would otherwise be 'solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short'.8 While Hobbes was defending a 17th century monarch under conditions of a civil war, the principle remains for a democratic state—state power is not natural but is a form of contract between the state and its citizens. On the frontispiece of Hobbes' book Leviathan (designed with Abraham Bosse) the king is depicted transcending the landscape and city with his body formed by the bodies of citizens. He holds the symbols of force and religion in each hand and the trappings of power below include castles and churches along with weapons, instruments of torture and the Star Chamber. These days we seek to break with monarchy, to separate church and state and to hide the torture, and the legitimating images have become much more sophisticated. However, Hobbes' key insight retains its resonance—that the state is a contract to protect citizens and therefore requires our agreement, which we can always withdraw.

This idea of power as embodied in citizenship can be linked to the work of Hannah Arendt, who defines power as something that is produced when citizens act together in the public realm—'Power corresponds to the human ability not just to act but to act in concert'.9 For Arendt, power is the opposite of violence. In her inspiring words:

Power is actualized only where word and deed have not parted company, where words are not empty and deeds not brutal, where words are not used to veil intentions but to disclose realities, and deeds are not used to violate and destroy but to establish relations and create new realities. Power is what keeps the public realm…in existence.11

This brings us back to the distinction between power over and power to. Practices of power involve a complex intersection of top-down and bottom-up practices, power over and power to, formal and informal, authoritarian and democratic. This requires a multi-scalar understanding that does not presume that top-down trumps bottom-up.

The revolution in thinking about power initiated by Michel Foucault is crucial here— power is not something 'held' by agents so much as it produces a disciplined 'subject'.12 Power is distributed and exercised through the micro-practices of everyday life including the gaze of surveillance and the architecture of segregation. At the smallest scale any building plan mediates social encounters through privileged enclaves of access, privacy, amenity and control. Buildings produce and reproduce zones of surveillance and control on the one hand, together with privacy and privilege on the other. Some capacities are enabled while others are constrained. Deleuze and Guattari take this much further to celebrate the informal rhizomic practices of power that operate within and against tree-like formal hierarchies.13 In this sense power is neither good nor bad—it is what produces our world. The relationships of architecture to power operate at multiple scales and they are a complex assemblage of the formal and the informal.

Legitimating urbanism

Before I digress too far into theory I want to take a brief global tour of the trappings of power constructed in urban space.14 Here we find that urban design schemes that are used to legitimate the state have a good deal of formal congruence regardless of history, culture or degrees of democracy. These are regimes of large-scale urban order, replete with expressions of stability, straight lines or strict curves expressing discipline, hierarchy and social order. It is the condition of the state to maintain law and order and the forms of legitimation of the state tend towards the stable, the strict and the straight. This remains the case from older centres, such as Beijing through to Paris, Washington and Delhi, to the more recent designs in Kuala Lumpur and Astana (Kazakhstan). Canberra is no exception.

The word 'state' shares the Greek root 'sta' with words like stand, stable, static, statue, statement, standard, stage, status and establish. To legitimatise authority, architecture and urban design need to signify a stable system of law and order. Ideal forms such as the pyramid and dome embody the expression of stability, hierarchy and symmetry, a centralised order where power is concentrated and flows downwards and outwards. Relative scale works to signify power through the ways that urban prominence is read as dominance—large-scale urban form establishes a figure/ground relationship as a landmark. A centre of power is often established by verticality or horizontal expanse at a scale that overwhelms the human subject.

Figure 3: Centres of power—Astana, Delhi, Canberra. Images courtesy of Google Earth/Geo Eye

There is an aesthetic thrill, a pleasure in being overwhelmed by urban scale—a sense of the sublime to which we surrender when intimidation is mixed with awe and inspiration. The key institutions, monuments and rituals of state authority are arranged through an organisation of street vistas to produce a collective orientation towards the centres of power.

When major transformations of political power occur we often see transformations of urban form which produce a reorientation to new monuments, avenues and citadels of the new order. If the state can be identified with landscape and nature then this becomes a literal naturalisation of political power. The ground or earth upon which the city is based is the most stable of images. Architectural styles with a strong degree of formal order, symmetry and hierarchy are the most easily deployed as representations of law and order. The hierarchical order of the neoclassical resonates well with the hierarchic order of the state. Yet the neoclassical linked equally with both democracy and tyranny—there are no architectural styles that cannot be used to legitimate authority. Gothic revival architecture was chosen for the British Houses of Parliament where it resonates with the traditional connection of church and state, yet throughout much of the empire, where power was less legitimate, neoclassical held sway. Vernacular architecture can be used to evoke the idea that authority is indigenous and authentic—Hitler's passion for the German vernacular linked to 'blood and soil' remains a bit unnerving. Finally, urban design works as a stage set for the urban choreography of political rallies or the symbolic display of military force. The most interesting current version of this is enacted regularly on Kim Il-sung Square in Pyongyang.

Another key principle here is that the need for legitimation increases as power becomes more authoritarian.15 The more legitimacy you have the less you need the trappings—in an effective democracy they largely disappear. Extravagant expressions of legitimacy through urban form tend to emerge in new or vulnerable states. The Parthenon was in part a legitimating gesture linked to the threat to the Athenian state from the Peloponnesian War.16 New Delhi was built by the British just as their power in India declined. Indeed, the design of the new Australian Parliament House has been interpreted by James Weirick as a response to the legitimation crisis produced by the Whitlam dismissal in 1977.17 Such crises occur when subjects of authority lose faith in its fairness. With their capacity to stabilise identity and symbolise a grounding of authority in timeless imagery, architecture and urban design are regularly called on to legitimate power in a crisis.

The Commons

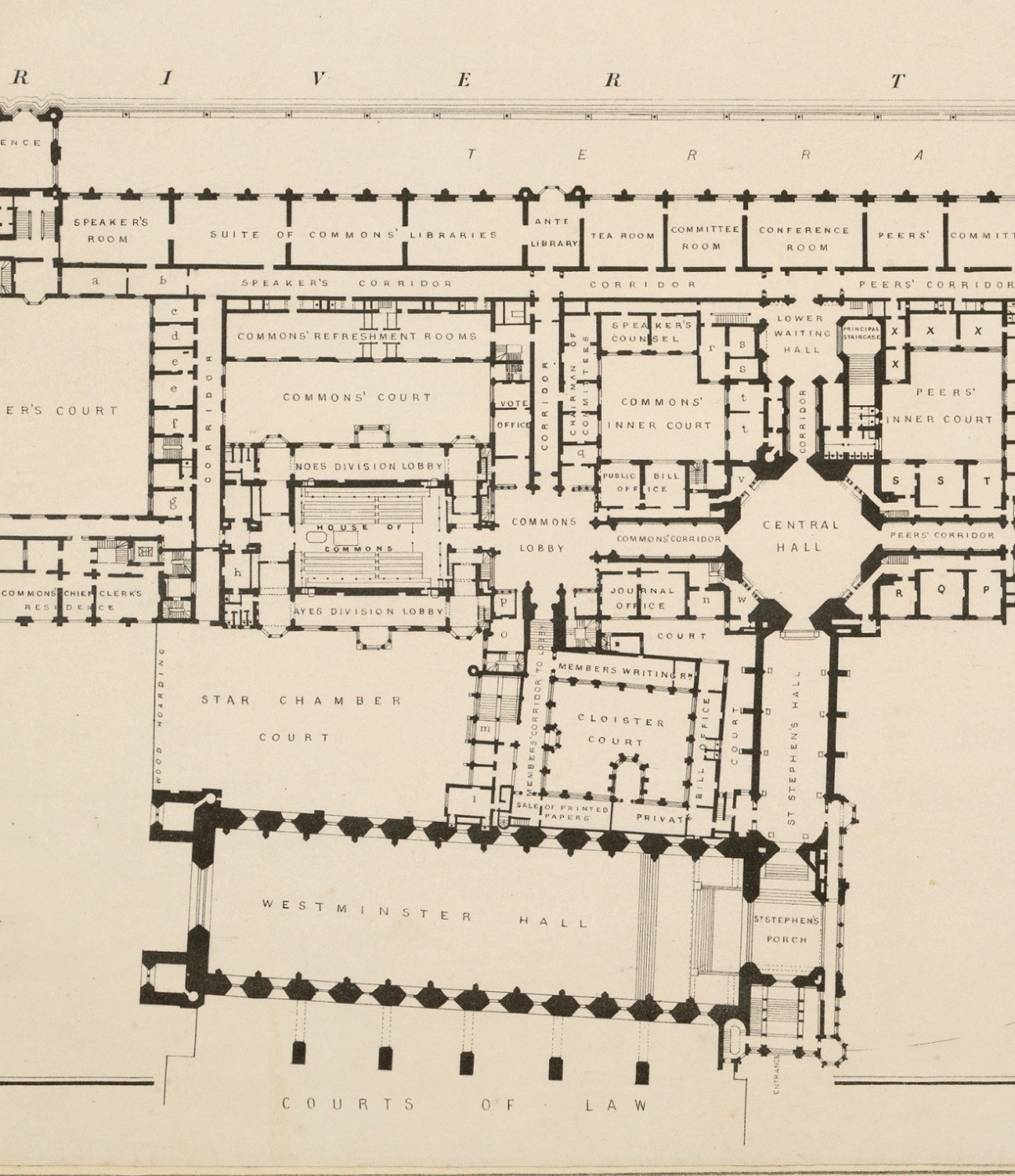

I want to zoom down now from larger to smaller scale and from the general to the particular. British parliamentary democracy was born in a chapel of the medieval palace at Westminster, where the first House of Commons was formed in 1547.18 The 13th century St Stephen's chapel was a chamber of about 20 by 11 metres with an altar at one end and tiered choir stalls lining both sides. The altar position became the Speaker's chair and members filled the stalls. The choir boys were replaced by the opposing parties, no longer singing to the same hymn sheet. The room was remodelled by Christopher Wren in 1707, adding galleries and the central table, but the spatial structure remained identical. The building was razed by fire in 1834 and Charles Barry designed a new building, with a relocated and expanded chamber of 21 by 13 metres set deep within the building after an enfilade of halls and lobbies (Figure 4).

Figure 4: British House of Commons, from the Plan of the Houses of Parliament and Offices, on the principal floor of the Palace of Westminster (1852). © British Library Board19

This building was the centre of an extraordinary amount of debate over issues of style. It was the key building of the 19th century 'battles of the styles', the struggle for priority between gothic and classical revival for prominence in public architecture. While these debates are of note, my interest here is on the way the debate over style obscured a non-debate over the spatial program which was largely removed from the architects' domain.20 However, this debate did erupt a century later when the Commons chamber was bombed in 1941 and Winston Churchill, in a speech arguing for its replication, made his famous claim which has become a catchcry of architectural determinism, 'we shape our buildings and afterwards they shape us'.21 The practice of oppositional debate was further inscribed as 'sword lines' about 3 metres apart were woven into the carpet, beyond which debaters were not permitted to step (Figure 5). This was designed as a space where it would be safe to be as aggressive as you might like—a crossing of swords without bloodletting.22

Figure 5: The British House of Commons, courtesy of UK Parliament23

While I am not normally a fan of spatial determinism, this polarised spatial structure with the two parties facing off at sword fighting distance does produce particular forms of discourse. The Speaker on the raised remnant of the altar calls for 'order' as members are reduced to shouting to be heard. This is a spatial framework that favours those, such as Churchill, who are skilled at loud debate from a standing position. In this sense it is also a 'men's house'—being naturally less dominant in height and voice, women are disadvantaged. In her recent anthropological study of the British House of Commons, Emma Crewe argues that 'Many women feel uncomfortable and hesitant in the chamber…men have more confidence, aggression, deeper voices and relish the quick repartee.'24 Churchill's determinism was overstated but the House of Commons is his best evidence. The behaviour it produces rarely occurs in other public debates or courtrooms, where the issues being debated are more important than the spectacle. The House of Commons was a place where rhetoric trumped policy. Churchill's arguments won the day and the House was rebuilt to a congruent design. However, this was not the first time the Commons had been reproduced.

Provisional parliaments

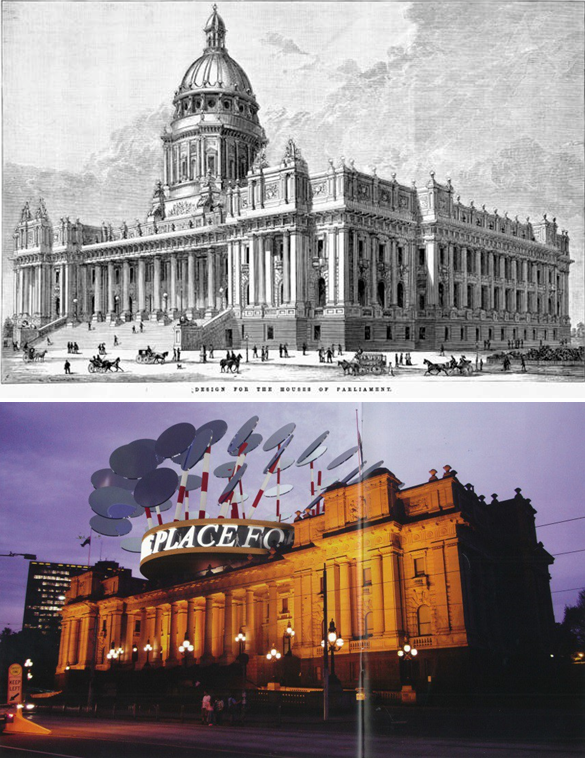

From 1901 to 1927, Australia's first provisional Parliament House was the Victorian Parliament House in Melbourne, designed by Peter Kerr and constructed in stages from the 1850s to 1890s. It was structured with the two houses flanking a central hall on a main axis as at Westminster but here located much closer to the street entry. The Legislative Assembly chamber closely resembled the British Commons with oppositional seating that was later converted to a horseshoe. The Melbourne grid was not designed as a capital and the chosen site was on a hill at the top of Bourke Street where it remains as a centrepiece of the so-called Marvellous Melbourne period.

However, once the 1890s depression collapsed the economy, the dome of the building was never completed, opening up other opportunities. One I like is a rather polemical vision by ARM Architecture for a grand function room, surmounted by a large public open space with a 'crown' of solar collectors (Figure 6). While we might debate the details, this is the kind of design thinking we need for a democracy of the 21st century.25

Figure 6: Victorian Parliament House as imagined by A.C. Cooke (1878) and ARM

Architecture (2006). Images courtesy of State Library of Victoria and ARM Architecture26

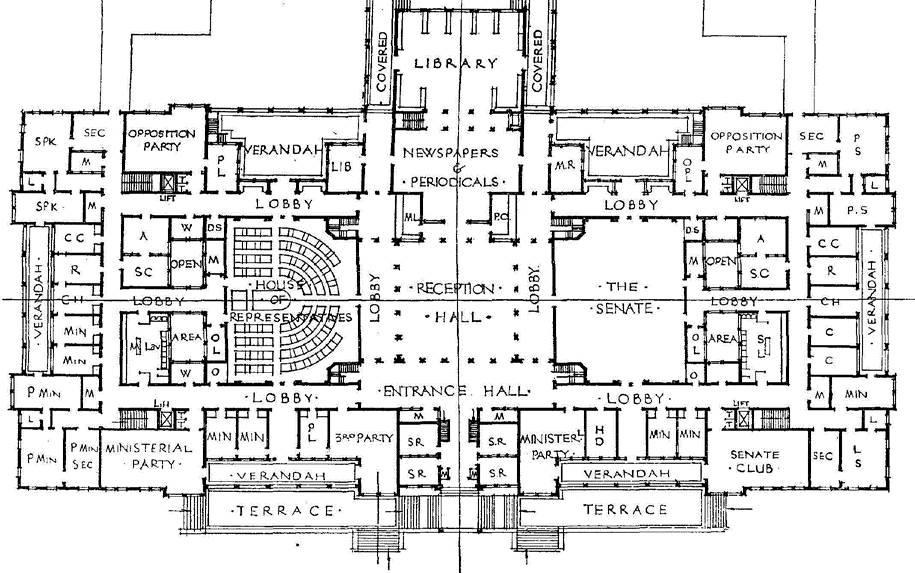

The Australian Parliament moved to Canberra in 1927 when the second provisional Parliament House, designed by John Smith Murdoch, was completed. The structure was very similar to the Melbourne building with the two houses flanking the central hall, again with a relatively direct entry from the street. The House of Representatives was much wider than the original and in a horseshoe formation, however, the structure of oppositional debate at sword fighting distance between front benches was maintained. The central hall was highly accessible with members and senators, the public and the press all crossing paths. Unlike its British predecessor, this building also housed the prime minister and cabinet in one corner of the ground floor, but with no executive enclave. A tradition of strong press access grew in this building. As Michelle Grattan wrote 'the old building is an intimate place. If something is going on it literally buzzes around the corridors. Ministers, backbenchers, staff and media cannot escape one another'.27 In this circumstance, informal rules emerged to regulate such contact. One of these was that members would make themselves available for 'doorstop interviews' on entering and leaving the building, provided that they were not asked for public comment in the corridors. The front steps became the scene of many such interviews.

The provisional parliament was not an effective emblem for a growing nation and it outlived its functions, but the paradox was that its dysfunctionality had a democratic function. Robert Haupt described it as a:

cheek by jowl jumble of corridors, rooms, cubicles and annexes so hated by those who worked there and yet so vital to our intimate political style in which a chance remark in Cabinet in the morning could become a pointed parliamentary question to the Prime Minister in the afternoon, the lead item to the evening television news and the subject of a scathing political commentary in the following morning's press.28

Figure 7: The main floor plan of the provisional Parliament House, Canberra29

Similar to the street, the corridor or lobby of a public building is no one's place and therefore everyone's. It is a place framed in such a manner that any conversation can be started or terminated at any time. It is a space 'between' functions where the flows of information are as unpredictable as the flows of people. Some things may be said in a lobby that will remain otherwise unsaid, and certain people may speak who may not otherwise be heard. It is a space of possibility. This was a building that embodied practices of democracy within its spatial structure. As a platform for such intensities of encounter the building worked like a small city, but in this sense the building did not 'work' for politicians.

Segregation

The design of the new Parliament House was the result of a public architectural competition and is largely the work of Italian/American architect Romaldo Guirgola. However, it is crucial to note that the architects were not responsible for any part of the spatial programming. The Parliament House Construction Authority produced two volumes of competition conditions that stipulated a clear segregation of people within the building and four separate entrances for the executive, Senate, House of Representatives and the public. Internal divisions were equally explicit—'Circulation space around and between chambers at chamber floor level should not be accessible to tourists’—citizens were reduced to ‘tourists’. Ministers and backbenchers were also separated—‘Ministers…should not have to use a circulation system flanked by Senators’ suites’.30

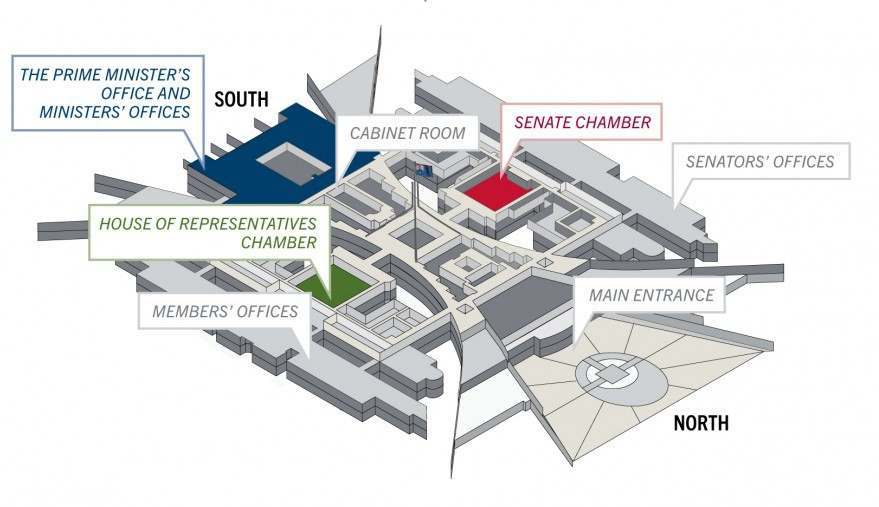

Figure 8: Floor plan of the Australian Parliament House

The program largely determined the plan since it diagrammed the various parts of the building with the two houses as wings of a cruciform with the new executive on the axis at the top (Figure 8).31 Any competition entry which did not reproduce some version of this diagram with its four distinct entries could not meet the brief—the winning plan was one of very few competition entries that did.32 The plan was essentially four separate buildings in a cruciform with four entrances for four classes of people whose paths rarely cross.

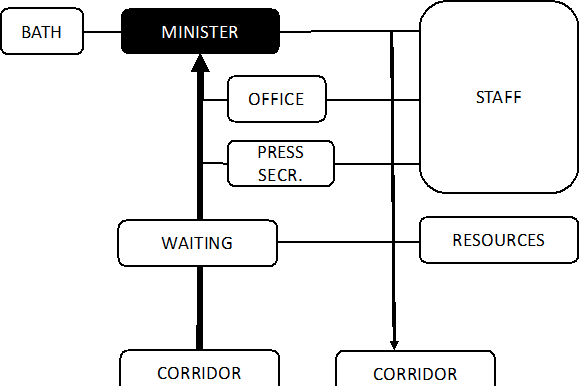

The executive entry is on the axis opposite the public entry and it grants ministers a high level of control over press contact, renders the doorstop interview voluntary and grants them media access on their own terms. Within the executive block each minister is provided with a suite of about nine rooms, the spatial structure of which was completely determined and diagrammed in the program (Figure 9).

Figure 9: Spatial program for ministerial offices (based on Parliament House Construction Authority diagram, 1979)

Such diagrams are the spatial genotypes of how power is practised through spatial segregation.33 The minister's office is several segments deep from the access corridor and is structured to enable a 'backdoor' entry and exit. Thus just as the minister can regulate contact with the press as she enters the building, the same is possible with anyone entering or exiting the office. This spatial structure juxtaposes a formal entry suite with an informal back suite of advisors that also serves as a back entry/exit. This genotype is the standard that has developed over centuries from western palace architecture where an enfilade of formal rooms leads to the centre of power, which is then serviced by an informal entry/exit for mistresses and informal advisors. The cabinet was originally named after a small room for informal advisors located near the king's bedroom.34

The general argument here is that the building reflects a shift in power from parliament to executive, counter to the interests of the press and citizens. A survey of the press soon after completion found that a majority felt the building had caused an increase in the power of the executive. However, informal power works in multiple ways and it has also been argued that the new building enables the plotting for leadership coups to be carried out in greater secrecy. The building has also rendered the corridors of power somewhat dysfunctional. The severely bloated spatial program causes a proliferation of corridors and lobbies that dissipate all intensity. It has been criticised from this perspective by everyone from Barry Jones 30 years ago to Malcolm Turnbull. The doorstop interview with ministers has been largely replaced by the staged forecourt interview, which at least keeps the minister fit since it requires a five minute walk each way.

House as hill

While the spatial program was largely decided by politicians and bureaucrats, the architect's primary legacy lies in the forms of representation and the composition of the building. Burley Griffin's urban design for Canberra was to leave this site, Capital Hill, as a public open space from which to look down and across the parliamentary triangle to the water. The decision to locate Parliament House on the hill is just one in a long series of violations of the Burley Griffin plan driven by a variety of bureaucratic and political imperatives. One of the attractions of Guirgola's design was that it resisted the impulse for an imposing edifice. Instead the building excavates several storeys off the natural landscape which it then reconstructs artificially. This tactic enables a very large building to blend into the landscape and one enters the parliament as if into the land it stands for—Parliament House as a hill rather than on the hill. Citizens could initially walk on top to produce a potent legitimating image, although that access is now sadly denied.

The public parts of the building comprise a sequence of spaces from the grand entry plaza through to the heart of the building. This spatial and architectural narrative proceeds from the grand plaza, representing Aboriginality and the desert, to the building entry which is depicted in terms of the arrival of European civilisation. The walls and building entrance containing the forecourt signify Greek and Egyptian architecture as they accentuate the sense of entering the earth and the rise of European civilisation. The main entry space also signifies the 'colonial verandah', which reconstitutes and frames the colonial gaze back over the Aboriginalised landscape. The deliberate use of a semiotic approach to architecture results in guides and guidebooks decoding the building for citizens who must learn how to see it.35 The grand foyer of marble columns is meant to evoke the hall of Old Parliament House but here it is stripped of its members. This is followed by the Great Hall and finally the new Members Hall, flanked by the two houses. Here the House of Representatives— why did we ever abandon that wonderful word 'Commons'—has been expanded in size yet again, as if the architecture might ameliorate the intensity of political debate. Here we also find the programming of separate lobbies for the government and opposition—whatever happened to the ideal of a common public realm?

The new Members Hall between the chambers is the symbolic centre of the nation. In the architects' drawings this was the key node point of the building, filled with members chatting and lobbying. Yet members have no reason to be there and it is generally empty (Figure 10). The large square slab of water covered black granite becomes a mirror designed to promote contemplation and to signify permanence and purity, surmounted by the pyramidal roof and flagpole. What it most evokes is contemplation of what kind of democracy we have become, together with a desire to throw coins and to wish the hall were not so empty. The throwing of coins is a refreshing spectacle since nowhere on the site does the building provide any genuine public space for political speech.

While the architects should have known this would happen, the emptiness at the centre of parliament is largely produced by the program they were forced to follow. It can also be seen as an early and uncanny reflection of global transformations that were accelerating from the 1970s—now generally known as neoliberalism, the Washington consensus or a 'post-democratic' condition.36 From this view, the power of the nation state is in decline as the global neoliberal consensus holds sway. The state becomes more corporate and political power shifts from parliament to the executive. Public cynicism about politics rises as commitment to democratic institutions falls and parliamentary democracy is viewed by many as an empty charade.

Visible above the empty Members Hall is the giant pyramidal flagpole representing a symbolic joining of the two houses with the executive and public entry. Some critics have argued this is a weakness of the design, yielding as it does rather directly to heroic patriotism and its likeness to the icon of the Italian Fascists—a bunch of 'fasces' lashed together with an axe. In my view this is not a helpful critique since these are just the normal trappings of power—the state always seeks images of disparate parts conjoined into an aspirational whole. And without the flagpole one would not even see Parliament House from a distance.

So what might be done about this post-democratic house on the hill? With regard to Parliament House itself, I would suggest not a lot. One cannot change the circulation structure dramatically, nor shrink the building or its chambers. The architectural composition of the building is beautiful in many ways and will only be damaged by major changes. We could start with granting public access to the central hall because there is no reason members should not mingle with citizens, as they do with safety in the street every day. While this may not change the practice of politics, it would at least relieve the image of such an empty centre. We could also reopen the roof as a public park—the parliament belongs to its citizens and should not be expropriated in an endless and ultimately hopeless quest for 'security'. However, if we were to think a little more broadly about this house on the hill perhaps more transformational change is possible.

Re-framing parliament

At the larger scale of the urban landscape Parliament House is a citadel, separated from the city by three broad ring-roads which make it nearly impossible to approach on foot. The practices and representations of democracy have been segregated from the community. The main approaches to the parliament show it in a bushland setting, an effect that has been achieved by encircling parliament with a vast moat of parkland (Figure 11). While I am sure there are many who will leap to the defence of this parkland and Burley Griffin's long-lost vision, spare me two minutes to launch a small thought bubble wherein we might see this as a space of possibility. Ninety per cent of Australian citizens live in urban environments. We may complain about our cities and escape from them when we can, but we vote with our feet because cities are where most of the jobs and opportunities are. Canberra is a city that pretends to be bushland and achieves this only with a very low density and a devotion to cars.

The key challenge for all Australian cities is that they are so heavily car dependent, and while we rave on about walkability and about healthy and low-carbon cities we so rarely build them. The closest we come are those popular inner city neighbourhoods with medium-density housing, a lively mix of places to live, work and visit, serviced with good public transport. So why not turn the moat of parkland enclosing Parliament House into a new inner city (Figure 12). Even if we were to leave the 20 hectare citadel as it is, the moat occupies a further 30 hectares of space all within a 400 metre walking distance of the centre. What are the possibilities if this area were developed to about four to ten storeys, while leaving the triangular slice facing the lake clear for symbolic purposes (or a possible Aboriginal embassy)? If programmed with a mix of residential, office, retail and other uses, then this could become a popular new suburb of Canberra, housing substantial populations, facilities and opportunities within walking distance of parliament. Why not use some innovative and agile thinking to demonstrate how a low-carbon, walkable city can work— a 'smart city', 'healthy city', 'productive city', 'creative city'. Perhaps we could invent some new slogans to help change the national imaginary.

What Parliament House needs after 30 years is some neighbours and a transformation of the national imaginary. A citizen is a denizen of the city—this would put the city back into citizenship, re-framing parliament to reflect where 90 per cent of all Australians live. Putting the politics back into the polis where it began might also help to legitimate the authority of the nation in a different way for the centuries to come. It might indeed make Canberra a little more resilient—history tells us that cities last longer than nation states.