Standing Committees

23 Regulations and Ordinances

-

A Standing Committee on Regulations and Ordinances shall be appointed at the commencement of each Parliament.

-

All regulations, ordinances and other instruments made under the authority of Acts of the Parliament, which are subject to disallowance or disapproval by the Senate and which are of a legislative character, shall stand referred to the committee for consideration and, if necessary, report.

-

The committee shall scrutinise each instrument to ensure:

-

that it is in accordance with the statute;

-

that it does not trespass unduly on personal rights and liberties;

-

that it does not unduly make the rights and liberties of citizens dependent upon administrative decisions which are not subject to review of their merits by a judicial or other independent tribunal; and

-

that it does not contain matter more appropriate for parliamentary enactment.

-

-

The committee shall consist of 6 senators, 3 being members of the government party nominated by the Leader of the Government in the Senate, and 3 being senators who are not members of the government party, nominated by the Leader of the Opposition in the Senate or by any minority groups or independent senators.

-

The nominations of the opposition or any minority groups or independent senators shall be determined by agreement between the opposition and the minority groups or independent senators, and, in the absence of agreement duly notified to the President, the question of the representation on the committee shall be determined by the Senate.

-

The committee shall have power to send for persons and documents, and to sit during recess.

-

The committee shall elect as chairman a member appointed to the committee on the nomination of the Leader of the Government in the Senate.

-

The chairman may from time to time appoint a member of the committee to be deputy chairman, and the member so appointed shall act as chairman of the committee when there is no chairman or the chairman is not present at a meeting of the committee.

-

Where votes on a question before the committee are equally divided, the chairman, or the deputy chairman when acting as chairman, shall have a casting vote.

-

The committee may appoint with the approval of the President counsel to advise the committee.

Amendment history

Adopted: 11 March 1932 as SO 36A, J.45–46 (also see 4 March 1932, J.27–29)

Amended:

- 1 September 1937, J.44 (to take effect 1 October 1937) (to provide a method for filling vacancies on the committee)

- 2 December 1965, J.427 (to take effect 1 January 1966) (changes in terminology and timing: committee to be appointed at the beginning of each “Parliament” rather than each “Session”; and exclusion of Northern Territory and Territory of Papua and New Guinea regulations and ordinances from terms of reference)

- 23 August 1979, J.883–84 (recasting of terms of reference in more general terms)

- [22 September 1987, J.96 (sessional order – reduction in membership from seven to six and quorum from four to three; inclusion of minority groups and independent senators in the membership formula clarified; chair designated as a government senator; provision for appointment of deputy chair, and casting vote of chair and deputy chair when acting as chair)]

- 24 August 1994, J.2053 (to take effect 10 October 1994) (committee-specific quorum provision deleted

1989 revision: Old SO 36A renumbered as SO 23; restructured; language simplified; principles of scrutiny incorporated; provision for appointment of a legal adviser formalised; changes made by 1987 sessional order incorporated

Commentary

Senator Digger Dunn (Lang Lab, NSW) who, with his colleague Senator Arthur Rae (Lang lab, NSW) was suspended during the debate on the composition of the Regulations and Ordinances Committee ( Source: Commonwealth Parliamentary Handbook)

The Senate’s oldest standing committee other than its domestic committees, the Regulations and Ordinances Committee was established in 1932 following the acceptance of recommendations made by the Select Committee on the Standing Committee System.[1] The principles of scrutiny, followed by the committee, and eventually incorporated into the standing order in the 1989 revision, were originally set out in the select committee’s first report, presented in 1930.[2]

The committee’s original terms of reference provided for the referral of “[a]ll Regulations and Ordinances” to the committee “for consideration and, if necessary, report there on”. In its Fifteenth Report in 1959, the committee pointed out that it did not see the need for it to scrutinise ordinances of the Northern Territory and the Territory of Papua and New Guinea which were made by the Legislative Councils of those territories. It took several years of persuasion and reminders but the committee’s goal was eventually achieved on 1 January 1966 when an amendment to exclude these ordinances came into effect. The terms of reference were recast again in 1979 to formalise the committee’s practice of scrutinising all legislative instruments subject to disallowance, notwithstanding that they may not be called regulations or ordinances. The committee proposed an amendment in its Sixty–second Report,which was then considered by the Standing Orders Committee and recommended for adoption. Instead of referring to regulations and ordinances, except those of the Northern Territory,[3] the revised terms of reference were more generic, referring to all “regulations, ordinances and other instruments, made under the authority of Acts of the Parliament, which are subject to disallowance or disapproval by the Senate and which are of a legislative character”.[4] As the Standing Orders Committee report noted, the interpretation of the expression “of a legislative character” was a matter for the Regulations and Ordinances Committee. The meaning of “legislative instrument” has subsequently been codified to a large extent by the Legislative Instruments Act 2003.

Senator Arthur Rae (Lang Lab, NSW) ( Source: National Library of Australia)

When the committee was established, its membership formula[5] was a cause of concern in some quarters on the basis that both the government and opposition then consisted of two distinct party groups and there would need to be a means to ensure that those groups would be fairly represented in the nomination process. The division of three opposition places between two groups exercised NSW Lang Labor Senators Rae and Dunn who were both suspended during the debate for disorderly conduct.[6] In the event, members of the first Regulations and Ordinances Committee were appointed without further controversy and Senator Rae was amongst them.[7] A minor amendment resulting from the1937 revision set out a process for filling vacancies on the committee that would preserve the membership formula.[8]

The 1938 MS contains extensive notes on the operation of the committee informed by Edwards’ experience as its first secretary. He comments on its non-party operation before explaining how the committee applied the principles of scrutiny (now contained in paragraph (3)):

It was considered that the Standing Committee should not set itself up as a critic of governmental policy or departmental practice apart from the tests outlined above [in the four principles of scrutiny], and indeed that such criticism was not within its province. Accordingly, early in its existence the Committee decided that questions involving Government policy in regulations and ordinances fall outside the scope of the Committee.

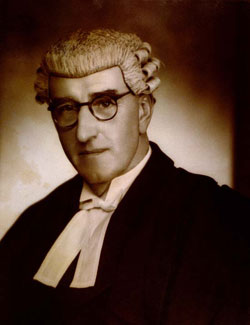

First secretary of the Regulations and Ordinances Committee, John Edwards (later Clerk of the Senate) (Source: Commonwealth Parliamentary Handbook)

Edwards goes on to describe the operational practices of the committee, including weekly meetings in sitting weeks, distribution of copies of all instruments to each committee member, and the provision by the responsible department of explanations of, and reasons for, the instruments. These are now formalised as explanatory statements which are tabled alongside the instruments but they were originally filed and kept for reference by the Clerk of Committees (Edwards) who noted that “[i]f any of them appear to him to be inadequate or unsatisfactory he seeks further information prior to the Committee meeting”. As with the Publications Committee (see SO 22), it is remarkable how closely the committee’s foundation practices continue to underpin its contemporary operations. Some of these practices were described in the committee’s Fourth Report, presented in June 1938.[9] The committee’s work has also been comprehensively described in its 71 st Report – 50th Anniversary of the Committee (PP No. 47/1982) and 85th Report– Overview and Future Directions (PP No. 464/1989), as well as in subsequent annual reports.

A major subsequent development was the engagement of a legal adviser (with the approval of the President) to advise the committee on some of the more technical aspects of its scrutiny function, and as a way of managing the increasing volume of instruments to be scrutinised. This practice had been foreshadowed in the select committee report but dates from the mid–1940s. As secretary, Edwards played a critical role in advising the committee to appoint an independent, external adviser, rather than accepting an offer from the Attorney-General for a departmental officer to assist the committee.[10] The legal adviser’s role was not formally recognised in the standing order until the 1989 revision, when it was added to reflect a similar provision for the much more recently established Scrutiny of Bills Committee (see SO 24). That explicit provision had itself been based on the long-standing practice of the Regulations and Ordinances Committee.

J.A. Spicer, first legal adviser to the Regulations and Ordinances Committee (also a former senator and committee chair) (Source: Commonwealth Parliamentary Handbook)

The reason for the committee’s quorum being set at four rather than the usual three is also the subject of commentary in Edwards’ notes to old SO 37 (Quorum of Standing Committees). The committee’s first chairman, Senator Sir Hal Colebatch (Nat, WA), suggested that the quorum should be reduced to three because of the difficulty of getting members together in Canberra but Government Leader, Senator Pearce (UAP, WA), opposed the reduction on the grounds that it would be extremely dangerous for the quorum to be less than a majority of the committee.[11] By sticking to its principles of scrutiny the committee has always been able to operate in a non-partisan manner and avoid the procedural “dangers” that criticising government policy may have led to. Nonetheless, when changes were made by sessional order in 1987 to reduce the membership to six and the quorum to three, the precautionary government majority on the committee was maintained by designating the chair as a government senator and giving the chair a casting vote if the votes were equally divided.[12] These precautions have not needed to be activated as the committee continues to operate by consensus.

The 1994 changes to make committees more responsive to the composition of the Senate left the committee with its government chair and his or her ability to appoint a deputy chair. In practice, however, the deputy chair of the committee is a non-government senator. As part of the 1994 changes, the specific quorum provision was removed from the standing order, leaving the general quorum provisions in SO 29 to apply. This change provided greater flexibility but also ensured cross-party balance at meetings.

The committee has power to send for persons and documents and to sit during recess, but not the power to move from place to place which has not proved necessary, the bulk of its business being transacted during sitting weeks.[13] It also lacks the power to take evidence in public, which can be conferred by authorising resolution of the Senate should the committee require it.