83 Moving of motions

-

A senator at the request of another senator who has given notice may move the motion of which notice has been given.

-

If a senator fails to move a motion of which notice has been given when it is called on, it shall be withdrawn from the Notice Paper.

-

After a motion has been moved, it is in the possession of the Senate, and cannot be withdrawn without leave.

-

A motion which has been superseded, or, by leave of the Senate, withdrawn, may be moved again during the same session.

Amendment history

Adopted: 19 August 1903 as SOs 114, 115, 117 and 119 (corresponding to paragraphs (1) to (4))

1989 revision: Old SOs 121, 122, 124 and 126 combined into one, structured as four paragraphs and renumbered as SO 83; language modernised and simplified

Commentary

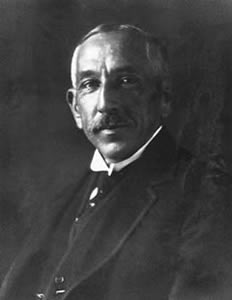

Prime Minister William Morris Hughes, whose plan to petition the United Kingdom Parliament to alter the Constitution of Australia Act so that he would not have to face an election in 1917 was thwarted by use of a simple Senate procedure (Source: National Library of Australia)

Paragraphs (1), (3) and (4) reflected the practice in South Australia with its typical elements of pragmatism and flexibility in the first and last paragraphs, and institutional propriety in the third. The second paragraph reflected nearly universal practice. Adopted without debate in 1903 and amended only in form but not in substance, SO 83 contains elementary but fundamental rules of procedure.

A great deal of business in the Senate is conducted by senators on behalf, and at the request, of other senators. This includes motions moved by one minister on behalf of another, by party whips on behalf of committee chairs or individual senators or, with respect to suspensions of standing orders moved pursuant to contingent notice, by senators at the request of a party leader in whose name the contingent notice stands. A statement that a senator is moving a motion at the request of another is taken at face value.

Failure to move a motion when it is called on results in the notice being withdrawn from the Notice Paper (but see below for an exception). This is one of several methods of avoiding a vote on a matter (other methods include postponing the notice of motion, adjourning the debate once the motion has been moved and, in extremely rare cases, moving the previous question[1]). In the 1938 MS, Edwards cites a specific example of a minister deliberately refusing to move a motion when it had been called on. It occurred in 1917 during a time of great controversy. The Prime Minister of the day, William Morris Hughes, attempted to extend the life of the Parliament beyond its constitutional limits by petitioning the British Parliament to use its imperial legislative power to amend the Commonwealth of Australia Constitution Act. It was a desperate measure which would have undermined the fledgling independence of Australia’s institutions of government.[2] The motion had been agreed to by the House of Representatives but was on the Notice Paper of the Senate where things were much less certain. According to Edwards, the Senate was evenly divided and the Leader of the Government, Senator Millen (Nat, NSW), therefore moved a motion to postpone the matter to another day. This motion was lost on an equally divided vote, meaning that the matter was not postponed and would be called on accordingly. To avoid the loss of the substantive motion on the same basis, Senator Millen remained silent in his seat when the notice was called on by the Clerk. Edwards reports that Millen had to decide very quickly what to do and decided to take advantage of this standing order. The President then announced that as the business was not being proceeded with, it would fall off the Notice Paper. The Government later gave fresh notice of the same motion for the following week when it hoped for a change of fortune but, in Edwards’ words, “in the meantime a state of affairs developed which brought about an election, and the motion for the extension of the life of Parliament was not moved”. In fact, Hughes’ attempted manipulation of the Senate numbers affecting the representation of Tasmania had brought on a revolt by two Tasmanian senators within his own party that deprived it of the necessary margin.[3]

An exception to the rule in paragraph (2) is made for disallowance motions. If a senator in charge of a notice of motion for disallowance failed to move it when it was called on, the chair would be obliged, under SO 78, to provide an opportunity for another senator to take over the notice. For details, see Odgers’ Australian Senate Practice, 12th edition, p.339.

Prime Minister William Morris Hughes, whose plan to petition the United Kingdom Parliament to alter the Constitution of Australia Act so that he would not have to face an election in 1917 was thwarted by use of a simple Senate procedure (Source: National Library of Australia)