141 Requests not complied with

-

Messages from the House of Representatives referring to requests by the Senate which do not completely comply with the requests as originally made or as modified shall be considered in committee.

-

If a bill is returned to the Senate by the House of Representatives with a request not agreed to, or agreed to with modifications, any of the following motions may be moved:

-

That the request be pressed.

-

That the request be not pressed.

-

That the modifications be agreed to.

-

That the modifications be not agreed to.

-

That another modification of the original request be made.

-

That the request be not pressed, or agreed to as modified, subject to a request relating to another clause or item, which the committee orders to be reconsidered, being complied with.

-

If a message is returned from the House of Representatives completely complying with requests of the Senate as originally made or as modified, the bill, as altered, may be proceeded with in the usual way.

Amendment history

Adopted: 19 August 1903 as SOs 244, 249 and 245 (corresponding to paragraphs (1) to (3)) but renumbered as SOs 242, 245 and 243 for the first printed edition

Amended: 9 September 1909, J.122 (to take effect 1 October 1909) (minor amendment to paragraph (3) consequential on the adoption of SO 140(1))

1989 revision: Old SOs 255, 256 and 258 combined into one, structured as three paragraphs and renumbered as SO 141 ; language streamlined

Commentary

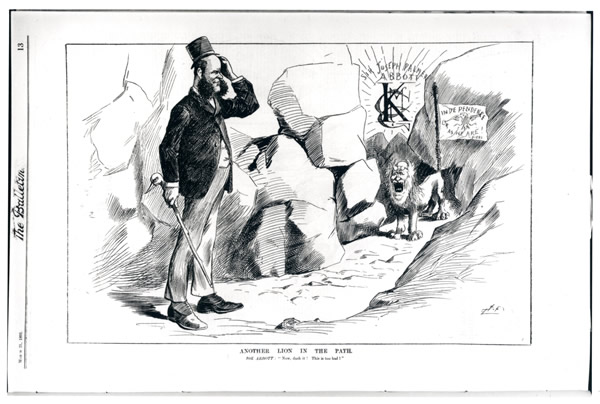

During the constitutional conventions of the 1890s there were several issues which threatened to prevent the formation of an Australian nation. The powers of the Senate in relation to financial legislation was one such 'lion in the path' but was addressed by the 'compromise of 1891' which provided the mechanism for the Senate to request amendments to such legislation (Source: The Bulletin)

For background on the adoption of this standing order, see the commentary on SO 140. This is a parallel provision to SOs 127 and 132 dealing with disagreements on Senate-originated bills and House-originated bills, respectively. Like those standing orders, it provides a wide range of options to the Senate that will maximise the chances of the Houses reaching agreement on bills that the Senate may not amend.

The powers of the Senate in respect of financial legislation and the relationship between the Houses on such matters were fundamental issues to be addressed by the framers of the Constitution. The breakthrough at the National Australasian Convention in Sydney in 1891 was the adoption of the idea behind the South Australian Compact of 1857, whereby the Senate could not amend certain financial legislation but could request the House of Representatives to do so. This was known as “the compromise of 1891 ”. As has been noted in the commentary on SO 140, attempts at the Melbourne session of the Constitutional Convention in 1898 to limit the Senate’s power in respect of requests failed and the fourth paragraph of s.53 was agreed to in its current form.[1]

During the constitutional conventions of the 1890s there were several issues which threatened to prevent the formation of an Australian nation. The powers of the Senate in relation to financial legislation was one such 'lion in the path' but was addressed by the 'compromise of 1891' which provided the mechanism for the Senate to request amendments to such legislation (Source: The Bulletin)

The Senate’s right to reiterate or press requests was codified in its original standing orders adopted in 1903. This issue in particular, and the Senate’s powers in respect of financial legislation in general, have been the subject of papers and treatises by Clerks of the Senate since the second decade of the Commonwealth, including:

-

C. B. Boydell (Clerk of the Senate, 1908–16), Notes on the Practice and Procedure of the Senate in relation to Appropriation, Taxation, and Other Money Bills; together with Standing Orders and Presidents’ Rulings; also a Summary of Cases Referred to (1901 –1910), tabled 6/9/1911;

-

G. H. Monahan (Clerk of the Senate, 1920–38), “Bills which the Senate may not amend,” notes on the rights and practice of the Senate to press requests for amendments, prepared for senators during the debates on the 1920–21 Tariff (unpublished, but preserved with the 1938 MS);

-

J. E. Edwards (Clerk of the Senate, 1942–55), “The Powers of the Australian Senate in Relation to Money Bills,” The Australian Quarterly, September 1943;

-

J. E. Edwards, Notes on various standing orders, 1938 MS (unpublished);

-

J. R. Odgers (Clerk of the Senate, 1965–79), Australian Senate Practice, 1 st to 6th editions, 1953–91, Chapter XVI, Money Bills;

-

Harry Evans (Clerk of the Senate, 1988– ), Odgers’ Australian Senate Practice, 7th to 12th editions, 1995–2008, Chapter 13, Financial Legislation; and

-

Harry Evans, Various papers on s.53 and amendments and requests, published in Papers on Parliament: Constitution, Section 53 – Financial Legislation and the Houses of the Commonwealth Parliament, No. 19, Department of the Senate, May 1993.

The issue has continued to be contentious because on most of the occasions on which the Senate has pressed requests, the House of Representatives has agreed to a resolution refraining from determining its constitutional rights or obligations in respect of the Senate’s message – but has considered the message anyway. Exceptions to this practice are noted in several of the works listed above. On many occasions, the Senate has, in response, resolved that the action of the House in receiving and dealing with the reiterated requests of the Senate “is in compliance with the undoubted constitutional position and rights of the Senate”.[2] For further analysis, see Odgers’ Australian Senate Practice, 12th edition, pp.309–11.

Messages from the House responding to requests made by the Senate are considered in committee of the whole (unless the requests have been made without any modification). Options available to the committee include any of the following motions:

-

to press or not press the request;

-

to agree or not agree to any modification made by the House;

-

to propose an alternative modification to the original request; and

-

that the request be not pressed or agreed to as modified, subject to an alternative request (to another clause or item) being made.

When any of these motions is agreed to, a message is sent to the House of Representatives conveying the Senate’s decision. Such messages may include the following variations:

The Senate does not press [or does not further press] its requests for the amendments which the House has not made and has agreed to the bill.

The Senate does not press its request for the amendment which the House has not made and further requests the House to make the amendments in the annexed schedule.

The Senate does not press its request for the amendment which the House has not made, has agreed to the amendments made by the House in its place and has agreed to the bill.

The Senate has resolved to press [or further press] its request for the amendment and again requests the House to make the amendment.

When a message is received from the House of Representatives indicating that the House has made the requested amendments, the Senate proceeds with the bill at the point at which it had reached when the request was made. In most cases, a motion for the third reading would follow unless the request was made at an earlier stage of proceedings. After the third reading, the bill is returned to the House with the following message:

The Senate returns to the House of Representatives the bill for <long title of bill>, and informs the House that the Senate has agreed to the bill as amended by the House at the request of the Senate.