100 Voting in divisions

-

A division may be called for only by 2 or more senators, but one senator calling for a division shall be entitled to have that senator’s vote recorded in the Journals.

-

A senator calling for a division shall not leave the chamber until the division has taken place.

-

A senator shall vote in a division in accordance with that senator’s vote by voice.

-

A senator shall not be entitled to vote in a division unless the senator is present when the question is put with the doors locked.

Amendment history

Adopted:

- 19 August 1903 as SOs 161, 162 and 163 (corresponding to paragraphs (1), (2) and (4))

- 11 June 1914, J.79, as SO 165A (corresponding to paragraph (3))

Amended: 2 December 1965, J.427 (to take effect 1 January 1966) (provision for an individual senator’s vote to be recorded in the Journals)

1989 revision: Old SOs 168 to 171 combined into one, structured as four paragraphs and renumbered as SO 100; language simplified and expression streamlined, including by rephrasing the numerical threshold in paragraph (1)

Commentary

The rules in SO 100 are straightforward enough and largely based on the South Australian precedents.[1] As adopted, and up till the 1989 revision, the requirement in paragraph (1) was for “more than one voice” to be “given for the Ayes’ and likewise for the Noes’”. This threshold provides a minimum safeguard against one vexatious senator but otherwise preserves the rights of senators in the minority to require a recorded vote. The threshold has not been varied despite the increases in the size of the Senate since 1949.

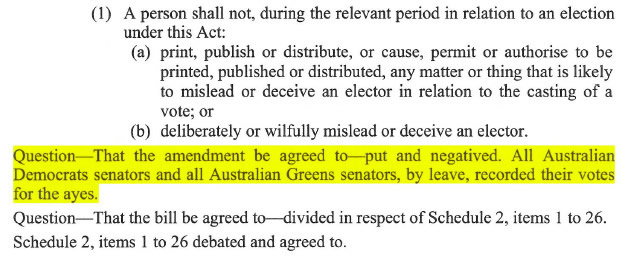

An extract from the Journas of the Senate showing the votes of members of a party being recorded by leave when there has been no division

In the 1938 MS, Edwards commented that an “exception” to the rule in SO 100(1) is when a division is required on the third reading of a Constitution alteration bill. Standing order 135 requires the third reading of such a bill to be carried by an absolute majority of the Senate, reflecting the requirement in s.128 of the Constitution. If any voice calls “No”, the vote is not unanimous and it is therefore necessary to divide the Senate. In an example cited by Edwards, Senator Millen (UAP, Tas) drew the President’s attention to the fact that he called “No” but that he did not wish to proceed to a division. The President ruled that there must be a division as “If the Senate is not unanimous there must be a division to enable me to ascertain whether there is an absolute majority voting in the affirmative, as required by the Constitution for the passage of the Bill”.[2] In more recent times, the votes of senators have been recorded regardless of whether there is any opposition to the question.

The requirement for a senator to vote in a division in accordance with the senator’s vote by voice was adopted in 1914. In debate, it was recognised that the amendment was “in accordance with the practice of the Senate and the practice of all Parliaments under the British flag” and was being added for clarity. Minor obstacles were raised but dismissed.[3]

The new standing order reflected a ruling of President Givens in the previous year[4] and was later the subject of an interesting ruling by President McMullin during a division on the second reading of the Loan (Housing) Bill on 20 November 1957. A senator proposed that the call for the division be withdrawn but an objection was raised and the division proceeded. Senators who had called “No” crossed to the right of the chair to vote with the Ayes. A point of order was raised and was upheld by President McMullin. The President directed those senators who had called “No” to return to places on the left of the Chair. When senators concerned failed to return to places on the left of the chair, the President called off the division and declared the question in the affirmative. In practice, where a large number of senators call “Aye” or “No” it is usually impracticable to monitor whether votes agree with the voices in individual cases.

Another ruling of President McMullin led to the amendment of paragraph (1) in 1965 to allow a lone senator calling for a division the right to have the senator’s vote recorded in the Journals.[5] The amendment was recommended by the Standing Orders Committee which saw it as part of its efforts to preserve the rights of senators in relation to motions or amendments that had not been seconded.[6] In relation to these, the committee recommended that the prohibition on recording such matters in the Journals be lifted. The right of a senator to have his or her vote recorded was seen as consistent with this principle.[7]

Senators in the minority may seek leave to have their votes recorded without proceeding to a division, and leave has invariably been granted by the Senate. The request to record votes often relates to senators who are not in the chamber. For example, the request is often in the form that all members of a party have their votes recorded.[8]