CHAPTER 3

Environmental concerns

3.1

Throughout the inquiry, many submitters and witnesses expressed concerns

about a range of environmental issues affecting flora, fauna and land across

Queensland. These include specific concerns about our iconic wildlife, such as

koalas and bats, native plants, world heritage listed areas, and the effects of

certain types of mining activities on human beings and domesticated animals.

The committee noted the outpouring of emotion in submissions and at hearings

from many individuals who have expressed fear for their lives and those of

their families, their animals, native flora and fauna, as well as a fear of

losing their livelihood because of large scale mining projects that are

encroaching on their land and homes.

3.2

While a very wide range of specific environmental issues were raised

with the committee, for the purposes of this report, the committee has outlined

several main concerns that were brought to its attention. These include

concerns that decisions are being made that are inconsistent with Australia's obligations

under international environmental law instruments, concerns about the

appropriateness of the federal minister for the environment delegating his

power to the state under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Act

1999 (EPBC), and the detrimental effects of coal seam gas (CSG) mining

activities.

Obligations under international environmental law instruments

3.3

Australia is a signatory to multiple international agreements that are

designed to guide us in the protection of our unique environment. A number of

witnesses and submitters expressed concerns that decisions are being made that

are inconsistent with Australia's obligations under international environmental

law instruments, including the Ramsar Convention that provides the framework

for the conservation and wise use of wetlands and their resources, and the

UNESCO World Heritage Convention.

3.4

The World Wildlife Fund (WWF) provided evidence that at a base level,

the chances of the Queensland government complying with our international

obligations are limited, due to the way in which Queensland has legislated.

As meeting the obligations of international environmental

treaties is the legal responsibility of the Australian Government, Queensland

Government legislation does not contain any specific measures or provisions

that would enable the Queensland Government to meet the obligations of Ramsar,

Jamba, Camba, Rokamba and other international treaties the Australian

Government is party to.[1]

3.5

The WWF provided details about a number of development actions and

practices that are currently being allowed by the Queensland government which

are inconsistent with Australia's international environmental obligations.

These include a number of projects within the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage

Area (GBRWHA).

3.6

This action has been compounded by legislative amendments that have

either removed or substantially weakened long standing environmental protection

measures, in order to facilitate economic development opportunities. The WWF

provided several examples, including:

-

Rescinding the Wild Rivers Act 2005 to enable agricultural

and mining development in Queensland’s last remaining pristine river basins;

-

Amending the Water Act 2000 to enable more water to be

extracted from waterways and aquifers for consumptive purposes, watercourses to

be deregulated and removal of Ecological Sustainable Development (ESD)

principles from the purpose of the Act; and

-

Establishing the Queensland Ports Strategy to enable new port

development adjacent to the GBRWHA.[2]

3.7

Mr Drew Hutton provided evidence about the Wild Rivers legislation

mentioned by the WWF:

Out in the Cooper Basin, it [the Wild Rivers legislation] has

got support from virtually all the stakeholders out there. The pastoralists,

the traditional owners and the environmentalists all accept the need for Wild

Rivers declaration over it – so did the Newman government, I might add,

initially. There is an enormous amount of shale gas reportedly out there. The

Newman government has simply rescinded that. There is no longer a Wild Rivers

proposal for the Cooper Basis. There will be, if the reports are correct,

extensive shale gas mining over that area. That is important because that is a

huge area that is drained by the Lake Eyre rivers and is highly significant

ecologically.[3]

3.8

Dr Aila Keto AO, President of the Australian Rainforest Conservation

Society Inc (ARCS), provided evidence that the former Queensland government had

reversed a number of decisions in contravention of Australia's obligations

under the Convention on Biological Diversity. These include decisions to

transfer 1.25 million hectares of State Forest and Timber Reserve to Protected

Areas in the Brigalow area. Dr Keto detailed concerns about the damage caused

by returning this land for timber production and grazing:

The ARCS report detailed the plight of woodland birds across

eastern Australia and identified the importance of the forests and woodlands of

the Southern Brigalow region in Queensland. The value of these forests and

woodlands to birds is severely impacted by grazing especially the practice of

regular intensive burning to maintain a grassy understorey preventing the

regeneration of a shrubby understorey that provides essential habitat. One in

four temperate woodland-dependent bird species is listed as threatened or declining,

with the Brigalow bioregion the most important remaining stronghold.[4]

3.9

Similarly, Cooloola Community Action (CCA) raised concerns that the

Ramsar Convention is being ignored because of plans to discharge untreated mine

wastewater from the proposed Colton coal mine directly into the Mary River,

just upstream of the Ramsar-listed Great Sandy Strait wetlands. Further that

recent development of three LNG export terminals and one new coal port, and

proposals for further coal ports, within the GBRWHA demonstrate a distain for

the World Heritage Convention due to discharge of mining wastewater into the

Fitzroy River catchment, which flows into the Great Barrier Reef.[5]

3.10

Mr Sean Hoobin from the WWF gave evidence that protections for the

GBRWHA have been eroded by both state and federal government:

Under the [World Heritage] convention, Australia has a duty

to ensure the identification, protection, conservation, presentation and

transmission to future generations of the cultural and natural heritage. It is

also stated it will do all it can to this end and to the utmost of its own

resources. I think it is arguable that Australia has not been meeting this

aspect of the convention. Currently, the World Heritage Committee is

considering listing the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage area as in danger

unless sufficient action is taken to address the condition and threats to the

reef.

Whilst Queensland is not the signatory, its role is critical,

and so are its policies and practices, as many of the actions it deals with

have a huge impact on the Great Barrier Reef. The Queensland government has

recognised this and has undertaken a strategic assessment and has also

participated in the development of Reef 2050, which is the plan for the

long-term sustainable development of the Great Barrier Reef. Both these were

intended to assure the World Heritage Committee that the reef is being well

managed. In these documents the Queensland government makes a number of claims

about the adequacy of its management and its commitments to improve management.

However, rather than improve policies and practices to protect the reef, the

Queensland government in the last three years has significantly weakened these,

flying in the face of Australia's obligations under international environmental

law. The committee notes that Queensland's biodiversity is unique and of

international importance, and is concerned by these and other issues raised

about activities being undertaken that are contrary to Australia's

international environmental obligations.[6]

3.11

The evidence outlined in this report indicates serious concerns exist

that Queensland is not meeting Australia's international environmental

obligations under a range of instruments. The committee shares the concerns of

individual submitters, and expert organisations, that the Queensland government

should observe Australia's environmental obligations, and take steps to protect

our environment.

Delegation of powers

3.12

Numerous submitters and witnesses, each concerned with different aspects

of the Queensland environment, indicated they believe it is inappropriate for

the Federal Minister for the Environment to delegate his approval powers to the

Queensland State Government under the Environment Protection and

Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (EPBC Act).[7]

For example:

3.13

Mr Innes Larkin of Keep the Scenic Rim Scenic summarised his views,

that:

...it is inappropriate for the Federal Minister to delegate his

approval powers to the Qld State Government under the EPBC act because it

places at risk areas of national and international significance.

Water tables do not recognise state boundaries, rivers do not

recognise state boundaries, World Heritage Listed National Parks do not

recognise state boundaries and tourists looking to see these international

treasures do not recognise state boundaries.[8]

3.14

Mr Glenn Beutel, a resident of Acland, Queensland expressed concerns

about mining activities taking place in and around Acland, and decisions that

have been made by the former Queensland government in respect of large projects,

such as the Newhope Stage 3 mining project. He expressed concerns about the

devolution of powers by the federal government:

I believe that the recent removal of red and green tape by

the former state government is going to make what has happened in Acland happen

in much of rural Queensland that is affected by open-cut mining and coal seam

gas production.[9]

3.15

The Stradbroke Island Management Organisation (SIMO) expressed serious

concerns about amendments to the North Stradbroke Island Protection and

Sustainability Act, initiated by the former Queensland government, allowing

a mining company to seek a renewal of mining leases to 2035, despite an

original agreement that mineral sand mining would end by 2019. SIMO expressed a

strong view against delegation of approval powers to the Queensland state government.

SIMO believes it is inappropriate and ill-advised for the

approval powers of the Federal Minister for the Environment to be delegated to

the Queensland State Government. We are particularly concerned to ensure the

integrity of the RAMSAR sites in Moreton Bay and Islands. In our view, the

recent performance of the Queensland Government in regard to mineral sand

mining on NSI [North Stradbroke Island] reinforces our concerns that delegation

of federal environmental powers will lead to significant reductions in the

level of protection of internationally important environmental sites.[10]

3.16

Mr Drew Hutton, President of Lock the Gate Alliance, spoke at length

about the problems associated with the lack of federal government oversight of

state decisions about large scale mining projects in Queensland. Mr Hutton

raised questions about the usefulness of Environmental Impact Statements (EIS)

and the approvals process, indicating that the federal government needs to take

more responsibility in these matters.

Where do we start? There are the assessments, for example,

that were given to the coal seam gas projects here in Queensland.

...

The federal government was placed in a corner by the state

government and gave their approval for that project despite the lack of that

vital material they needed to give federal approval. It is the same with the

water impacts, with the coal seam gas industry. The federal government did not

have that information and was backed into a corner by the state to give them

approval. Now the federal government, the Abbott government, is about to

relinquish their powers – they want to relinquish their powers – under the

Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act to the state

government that commenced these sorts of shenanigans in the approvals process.[11]

3.17

Ms Georgina Woods, also from Lock the Gate Alliance, added:

[T]he points we raised about the handover of federal powers

are very relevant in that area because there are these continental-scale water

reso8urces like the Murray-Darling Basin, the Lake Eyre Basin, the Great

Artesian Basin. The Great Artesian Basin is under siege from mining not just in

Queensland. There is a need for federal-scale, Commonwealth-scale oversight so

that the states do not, as we say with the Murray-Darling, make their own rules

and their own laws and disadvantage states or other users downstream of that

water resource.[12]

3.18

In discussing the Great Barrier Reef World Heritage Area, Mr Hoobin of

WWF stated:

We have argued quite strongly in submissions to the World

Heritage Committee that the most recent Queensland government has rolled back a

whole range of significant environmental protections, and so it is hard to see

how it could be given further power over development approvals and could look

after the Great Barrier Reef and the outstanding universal value of the reef.

So we would be of the view that giving the Queensland government more power to

approve and condition development would lead to an increased risk of an

in-danger listing for the Great Barrier Reef, definitely.[13]

3.19

The committee notes views that the power to make decisions about large

scale projects with potential to seriously effect Queensland's environment and

population, should not vest entirely with the state government. These views

reflect a broader notion that although CSG, coal and other resources are

physically located in Queensland, they are important to Australia as a whole,

as is the environment within which they are located.

Coal seam gas

3.20

The committee received submissions and heard evidence from numerous

individuals and organisations on a range of issues and concerns about CSG

mining in Queensland. This includes concerns about the location and proximity

of CSG gas wells to people.

3.21

The Queensland Government Department of National Resources and Mines,

provides information about CSG gas wells:

A gas well is a pressurised hole drilled in the ground,

reinforced with steel liners (well casing and production tubing), to extract

gas from underground seams. The casing is cemented into the ground and

underlying strata to ensure the well is isolated from all other rock strata

other than the coal seam reservoir producing the gas. At ground level the gas

well is fitted with a series of control valves, e.g. the well head.[14]

3.22

It states that hydraulic fracturing (fracking) 'is the process of

creating or enlarging cracks in underground coal seams (usually by pumping

fluid) to increase the flow and recovery of gas out of a well' and occurs in

around 8% of Queensland's domestic CSG wells.[15]

Tara and Chinchilla, Queensland

3.23

Tara and Chinchilla are rural towns in the Darling Downs region of

Queensland, north-west of Toowoomba. The area is traditionally agricultural,

producing meat, milk and a range of food crops. Coal mines, CSG wells and power

stations share the landscape, with mining exploration leases covering a large

proportion of the Darling Downs.

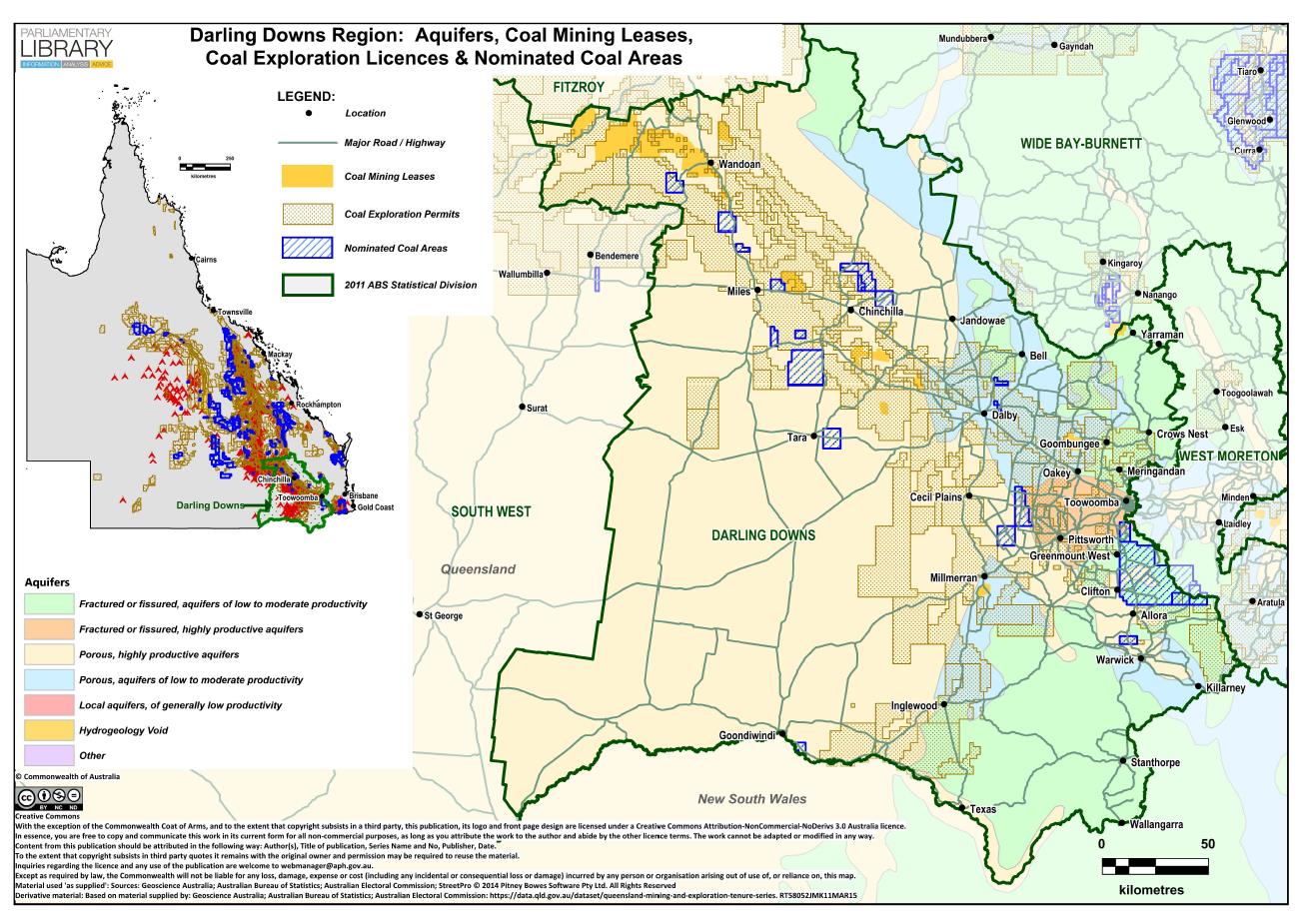

3.24

The map below shows the Darling Downs Region with aquifers and coal

related areas, including leases and exploration licences.

Figure 1: Acquifers, coal mining leases, coal exploration

licences and nominated coal areas in the Darling Downs region[16]

3.25

The committee received submissions and heard from a number of private

citizens living in and around the Chinchilla and Tara areas of Queensland as

well as from several community based organisations. Both individuals and

organisations raised concerns about local CSG mining activities, and in

particular about the effects on the health and wellbeing of people and animals,

the effects on the environment and the difficulties experienced by landholders

in dealing with the CSG companies.

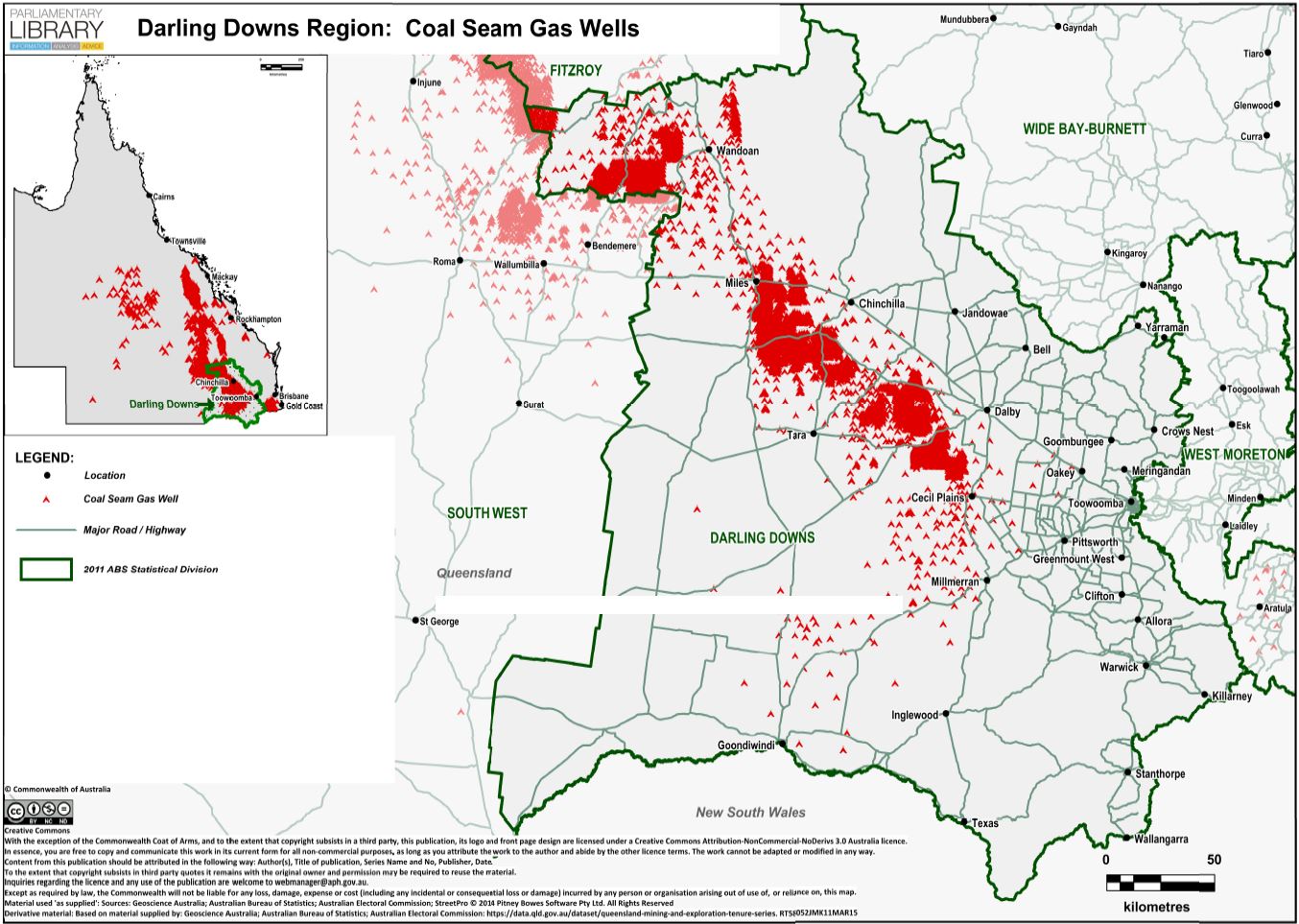

3.26

The map below shows the location of Tara and Chinchilla and the

concentration CSG wells in the area.

Image 2: CSG wells in the Darling Downs region[17]

3.27

While CSG was raised repeatedly throughout the inquiry, during a hearing

in Toowoomba on 19 February 2015, the committee heard from a number of private

citizens about the effects of CSG mining activities on their lives. The

committee is troubled by evidence from Tara and Chinchilla residents about the

effects on the health and wellbeing of themselves, their families and their

animals, as a result of contamination they believe is caused by CSG mining

activities in their local area.

3.28

Evidence was provided by a number of local residents about changes in

their health and wellbeing that they link to local CSG mining activities. For

example, Mr John Jenkyn talked about testing conducted in and around his

house that has shown chemicals such as formaldehyde present in his home. He

says he and his family are unable to drink the water from their rainwater tank

due to contamination, and that the disruptions, noise, light, odours, and dust

contamination have all contributed to the family's stress and other health

issues.[18]

I would say that I am a father of two adult disabled children

who moved out into the Tara-Chinchilla area 10 years ago, just for quality of

life. Within that time, QGC have moved in and have put in major infrastructure

– there is a reverse osmosis plant; I think there are four banks of compression

stations around us now; there are probably 200 gas wells – which has just impacted

severely on everybody's health in the area, as well as ours.[19]

3.29

A number of people spoke about the impact on their ability to enjoy

their land and homes, whether because of noise, dust or unknown individuals

having access to their land and impacting the surrounding area. For example, Ms

Glennis Hammond spoke about sometimes driving six kilometres from her home to

sleep in her van because of the noise generated by CSG mining activities.[20]

3.30

Mrs Veronica Laffy spoke about the negative impact on the ability of her

children to enjoy a safe space on the family's property:

There is a large impact on our personal amenity. We have six

children ranging in age from two to 15 years. One of our children has Downs

syndrome, so it is important for us that he has a safe place to live. Part of

what living with him involves is he may access the farm at any time. He can get

up at 5.30 in the morning and ride his motor bike up to the back of the farm

and back, which is awesome, but it is not awesome if there are people all over

the farm. Those people have not necessarily had background checks done, so you

would not really know the capacity of their involvement with children and what

that would mean for my children. So I would have to restrict their access to

our farm while that business was on our business.[21]

3.31

Dr Geralyn McCarron, General Practitioner, submitted that there is a

mismatch between notions of development in the area of Tara, and the reality of

people having to live in the midst of the CSG mining industry.

These major projects are often described as “development” but

their introduction has not brought better quality of life or additional

services to the local people. The residents live on rural blocks ranging in

size typically from 30 to 250 acres. They are surrounded by the infrastructure

of the gas industry. There are no shops, petrol stations, schools or other

basic facilities. The nearest doctor is in Tara which is an approximately 70km

round trip. Residents habitually travel to medical facilities in Chinchilla, Dalby

and Toowoomba where the regional base hospital is located.[22]

3.32

Mr Joseph Hill was one of several individuals who shared anecdotes about

visits to his property by CSG mining company employees seeking access to his

land, and the problems he has had in this respect. When asked whether he had

gas wells on his land, he said: 'No. I have taken the stand, as I said, since

2009, of standing up to them and using my constitutional rights to keep them

off.' [23]

3.33

Further, as a beef farmer, Mr Hill raised concerns about contamination

of overland water supplies[24]and

about pests, weeds and soil-borne diseases that can be brought onto private

land by vehicles.[25]

3.34

Mr George Bender, a pig farmer, provided evidence about bores on his

land that have dried up and now release methane gas and of pigs dying from

heart attacks, which has never previously occurred. Mr Bender maintains that

there is a link between these unusual events and local CSG mining activities.

I am George Bender from Hopeland, which is about 22 kays

south of Chinchilla. I have lived in that district all my life. We have been

dealing with the coal seam gas company since 2006 actually; but, more recently,

it is about what the gas is doing to the underground water. We have two bores

in Walloon Coal Measures, and the water is gone. Those bores are only releasing

methane at the moment. We measured them on Tuesday, and the methane that is in

them now is above explosive limits. That is all caused by the coal seam gas

industry, no ifs or buts about it. The water impact reports said there are 85

bores in the immediately affected area that the companies had to make good on.[26]

3.35

When asked to provide specific details about the sort of health issues

he was talking about, Mr Bender provided the following information:

It is not only human health; it is animal health. I own a

piggery. I have had pigs all my life and there are some things happening that I

have never seen happen before.

...

You go down to feed your pigs in the morning and come back

half an hour later—and they are gasping for breath.

...

They just die like that—heart attack. I cannot prove it is

coming from the gas industry or whatever, but you people should come out there

and watch these flares. What is coming in with these flares? The government

will not tell us and the industry will not tell us.[27]

3.36

These and other anecdotes raise questions about why these things are

happening in such a localised area, and whether they are in fact directly

related to the local CSG mining activities. Certainly, the residents of Tara

and Chinchilla believe they are, particularly given the timing and scale of the

health and other problems now being experienced in the area.

3.37

Dr McCarron is a General Practitioner who conducted a health survey in

Tara and produced a report outlining her findings.[28]

She collected data on how often local residents experienced things such as skin

and eye irritation, spontaneous nose bleeds, nausea and headaches, both before

and after CSG.[29]

Dr McCarron makes the point about her survey:

This small survey is not a comprehensive epidemiological

study. However it does refute the assertion that “just a handful of people are

complaining that their health is affected by CSG.” Furthermore, the character

and frequency of specific health complaints, particularly relating to potential

neurotoxicity in both children and adults are concerning.[30]

3.38

Dr McCarron also expressed concern that the Queensland government has

not sufficiently considered the health effects on people of CSG in the Tara

area. This is despite a commitment in June 2012 to investigate the growing

health complaints of residents. Dr McCarron noted in her submission in relation

to the Queensland government's investigation of health effects of CSG:

Between June 2012 and March 2013, no doctor employed by the

Queensland Government visited the residential estates to speak to the

residents. The township of Tara was the closest that the Queensland Government

doctors got to the source of the health complaints. Considering they were

investigating the health impacts of living in a gas development it is somewhat

surprising that no on-site visits were made.

In the nine months available to them, the Queensland

Government Departments failed to establish a comprehensive, systematic long

term testing regime to monitor potential chronic exposure to air or water borne

toxins. Instead they commissioned QGC, the gas company at the heart of the

residents’ health complaints, to undertake testing, creating a clear conflict

of interest. Sampling, which occurred as one off events at nine residences, was

entirely inadequate in scope and duration. Importantly, what is missing are

analyses of the gases produced in the localities concerned by flaring, well

leakages and pipeline venting.[31]

3.39

In relation to the way in which the Queensland government conducted its

investigation in the area, Dr McCarron expressed the view:

[I] reluctantly concluded that the Government had no real

commitment to investigate public health complaints related to CSG development.

As a general practitioner, I was concerned about the potential long-term damage

being done to the health of the people living in the residential estates. I

decided to carry out my own study to clarify whether or not the implication

that only a “handful” of people perceived health impacts was true, and then to

document these perceived health impacts.[32]

3.40

Of concern to this committee is the lack of information about the link

between CSG mining activities and the health and other impacts already being

experienced in places such as Tara and Chinchilla. When asked about where there

is information about the consequences and outcomes of CSG mining, Mr Sean

Hoobin of WWF stated:

The main issue is that no-one knows what the impacts of

mining and CSG, and the impacts on groundwater, will be. The government is

operating in a vacuum. Mining companies are operating in an information vacuum.[33]

3.41

A related issue raised is that the concerns of residents are largely

being ignored by the CSG companies, who are increasingly difficult to deal

with, and engage in behaviour that could be categorised as intimidating and a

nuisance.

3.42

Mrs Laffy gave evidence that as fourth generation farmers, trying to run

an organic farm in Dalby, she is concerned about the power imbalance that

exists in dealing with CSG companies and the government.

We are very concerned about the power imbalance that exists

when we are forced into negotiations with CSG companies and the government,

because the government has written the legislation that forces us to have to

negotiate. In our negotiations between 2009 and 2013 we have had to negotiate

with two different CSG companies, and the negotiations essentially involve us

agreeing to what they put in front of us or they threaten to take us to Land

Court. In my view that is not negotiating. They constantly intimidate us—it is

monetary intimidation because the cost of going to court would be in the

hundreds of thousands of dollars.[34]

3.43

Mr Jenkyn described the challenges he has faced in trying to deal with

the state government:

Really, I do not know what to say. It does not matter where

we go or who we deal with, nothing ever seems to happen. I have independent

testing that tells me it is not really good to live where we live and that you

cannot drink our water. You are flat-out just breathing the air some days, but

the government departments still sit on their hands – either that, or they deny

the testing.[35]

3.44

The committee also notes serious concerns raised by Mr Drew Hutton, that

people affected by decisions about mining, are being denied a right to object,

which effectively renders them powerless.

What it basically means is that it is virtually impossible

for any but a very, very small minority of Queenslanders to object to a mining

project in court. They cannot object. They have no appeal rights, whether it is

a small mine, whether it is a large mine or whether it is a mine that goes

through the Coordinator-General's department. They have no rights to object or

have their appeals heard in court.

...

This government is shelving the rights of ordinary

Queenslanders to have a say – even to the point, by the way, where the Newman

government has introduced changes to the role of the Coordinator-General where

he can designate a development as 'medium risk'.[36]

3.45

The evidence received by the committee suggests a widespread belief in

the Tara-Chinchilla area that CSG mining is taking a significant toll on the

health of the local population. Further, that there is an imbalance of power

which has left residents at the mercy of large, well-funded companies who

routinely ignore the rights of local residents.

3.46

The evidence also suggests there may be inadequate government support

available to residents affected by the CSG wells and related activities in

their local area. This is of concern to the committee, which is of the view

that the health and wellbeing of all Australians is paramount, and that

adequate resources should be in place to assist those facing health challenges.

Committee view

3.47

The committee received evidence about a range of activities that have

the potential to negatively impact Queensland's unique and important

environment. Numerous community and other groups have been established in an

effort to draw attention to concerns and to try and protect areas of

international and local importance.

3.48

The committee commends all those who are committed to raising awareness

about the environment and it encourages community consultation and discussion

about any development that may impact the environment and communities.

3.49

The committee shares the view that the future of Queensland's

environment is of vital importance to all Australians and should be afforded

the protection of federal government oversight - the federal Minister for the

Environment should not delegate his powers to the state under the EPBC Act. To

do so would place into doubt the future of the Queensland environment and would

amount to an abrogation of the Commonwealth's responsibility for matters of

national environmental significance.

3.50

Further, the committee is of the view that all levels of government

should take greater care when making decisions about projects that will impact

Queensland's environment. This should include engaging in open and transparent

community consultation and balancing economic development against the wishes of

the community and the need to protect the environment.

3.51

Specifically, the committee is of the view that more should be done to

ensure the health of individuals is monitored wherever there is CSG mining

activity, noting that CSG mining activities may also affect the practical

ability of people to enjoy their homes and properties due to noise, dust,

contamination and other disruptions.

3.52

It is of grave concern to the committee that the lives of so many

Queensland residents are being affected by decisions made about their

environment without adequate consultation, consideration for their wellbeing

and sometimes, apparently without respect for obligations to protect the

environment under international law instruments.

Recommendation 11

3.53

The committee recommends that the Queensland government ensure

all mining and other major development activities are consistent with

Australia's environment and social obligations under international

environmental instruments that Australia is a signatory to.

Recommendation 12

3.54 The committee recommends that the federal Minister for

the Environment does not delegate his powers under the Environment

Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

Recommendation 13

3.55 The committee recommends that the

Federal Minister for the Environment declare a moratorium on any new approvals

of Coal Seam Gas until an investigation is completed and reports back to

the Senate. The report should address the effects of Coal Seam Gas mining

activities in the Tara and Chinchilla areas on the health of local people,

animals and crops, groundwater and on the quality of soil, water and air, and

also investigate the disposal of effluent containing human faeces around

mining camps, local roads and agricultural land used for growing crops for

human consumption and the degradation of water reserves in these areas.

Recommendation 14

3.56 The committee recommends the Queensland government

undertake an immediate review of the Department of Environment and Heritage

Protection and its resource capabilities including staffing levels, expertise,

arms-length requirements and conflicts of interest to determine and establish

appropriate operating requirements for the delivery of quality outcomes for

stakeholders. Further, the committee recommends a thorough review of the

department to improve systems, processes, procedures, compliance, and

escalation of issues, transparency and reporting. Ideally, an independent body

should be established to manage escalated issues.

Recommendation 15

3.57 The committee recommends that the Queensland

Government complete a review of the Gasfields Commission Queensland including

roles, responsibilities, conflicts of interest and independence.

Recommendation 16

3.58 The committee recommends the Queensland government

review all legislation implemented by the Newman Government to determine its

appropriateness and compatibility with social justice/natural justice

requirements and other land ownership rights. Further the committee recommends

the review of mechanisms/instruments established by the Newman Government which

impose unjust and unfair limitations or requirements on land owners,

particularly in relation to land use/access issues.

Recommendation 17

3.59 The committee recommends that a royal commission be

established to investigate the human impact of Coal Seam Gas mining.

Recommendation 18

3.60 The committee recommends that a moratorium be called

and that no further Coal Seam Gas mining approvals be given until a full

investigation by the Federal Minister for the Environment has been completed

and reported back to the Senate on; the human health impacts, animal deaths,

crop contamination, drinking water and air quality, plus degradation of

the water supply in and around the Tara and Chinchilla area.

Recommendation 19

3.61 The committee recommends that a Resources Ombudsman

be established to provide Australians with an independent advocacy body.

Recommendation 20

3.62

The committee recommends that fracking be banned in Queensland.

Senator Glenn Lazarus

Chair

Navigation: Previous Page | Contents | Next Page