Papers on Parliament No. 47

July 2007

Prev | Contents

Introduction

The Australian national flag has become the most familiar of our national symbols. Less familiar is the Commonwealth Coat of Arms. Parliament House in Canberra, completed in 1988, displays both the flag high above the building, day and night, and the coat of arms above its front entrance.

Image 1: Parliament House, Canberra, showing the Australian Coat of Arms and flag

The bold central display at Parliament House provides a sharp contrast to the two sets of flags and arms—British and Australian—on Australia’s provisional parliament house completed in 1927, now known as Old Parliament House. The Union Jack and Australian blue ensign flew above the roof of that building, not every day but on special flag days. That dual display of flags has now gone. But the coats of arms, now painted (but not accurately) can still be seen above the rounded feature windows either side of the front entrance: the British arms on the left with English, Scottish and Irish symbols; and the Australian arms on the right with the symbols of the six federating states (image 2). The door knobs at the front entrance also display the British and Australian arms.

Image 2: British arms (left) and Australian arms (right), front entrance, Old Parliament House

Transition in the national flag

Official Australian national symbols began to emerge soon after federation in 1901, with the two shipping flags, the seal and the coat of arms, which were gradually adopted and adapted. But when did an Australian flag, the Australian nation’s chief symbol, replace the British flag as the national flag? Newsreel images of flags on Parliament House provide the answer. In June 1951, when Australians were celebrating the jubilee of federation, the Union Jack still took precedence as the national flag. In the jubilee celebrations shown in image 3, the Union Jack has the position of honour as the national flag at the viewers’ left, emphasising Australia’s British nationality.[1] Not until February 1954 did that change. During her visit in 1954 the Queen gave assent to the Flags Act, and image 4 shows the Australian flag in the position of honour over the Union Jack for the first time, when the Queen arrived at provisional Parliament House, Canberra. It took three more decades before Australians accepted that transition. But by then a Morgan poll showed that a growing percentage of them were questioning the place of the Union Jack on the Australian flag. By 1998 a small majority wanted a new flag.

Image 3: Jubilee celebrations of federation in June 1951, showing the Union Jack taking precedence over the Australian blue ensign on provisional Parliament House

Image 4: The Australian national flag took precedence over the Union Jack for the first time on the Provisional Parliament House in February 1954

Two questions

These facts about the national flag puzzle most Australians aware of them. The transition in national flag we made—and are still making—is not well known or understood. Nor are the roles played in that transition by people, pressure groups, political parties, parliaments and governments. They prompt two questions. Why did Australians take more than fifty years after federation to replace Britain’s Union Jack with an Australian flag, and still decades more to accept that change? Why is so little known about that history?

From Union Jack to Australian National Flag

Choosing a flag design

The unofficial federation flag

At its inauguration in January 1901, the Australian Commonwealth did not have an Australian national flag, though many Australians thought that the federation flag would become one. This popular flag, a British white ensign with a blue cross bearing white stars, was once used as an unofficial shipping flag along the east Australian coast from the early 1830s. During the 1898 federation campaign the Australasian Federation League of New South Wales promoted it as the flag for the new Commonwealth with the motto ‘One people, one destiny, one flag’. In 1901 it featured on invitation cards for the celebrations of January and May.

Image 5: Invitation to the Inauguration of the Australian Commonwealth, 1901, showing the federation flag

The flag’s St George cross with stars, similar to the symbol on the New South Wales blue ensign, was quite different from that on another flag prominent in the federation campaign: the Southern Cross constellation on Victoria’s red ensign. Its antecedent was the flag of the Australasian League of 1851, used in campaigning against the transportation of British convicts to Australia and New Zealand.

A design for two shipping ensigns

In 1900 a newspaper and a journal, both of Melbourne, first raised the issue of shipping flags for the new Commonwealth: blue for naval and official ships; red for commercial ships. The second competition was still underway when Australians celebrated the opening of the first Federal Parliament on 9 May 1901. One Australian had already complained to the Prime Minister, Edmund Barton that ‘every city, village, house, school and steamer is anxious to proclaim the Union of Australia, but not one can do so through the non-existence of our Flag.’ The flag that dominated the celebrations was the national flag, the Union Jack, introduced into state schools to mark the opening of the federal parliament.

Barton’s government, which had received a request from the British government for a flag design but was unable to agree on one, had launched its own competition for two shipping flags in April. The judges, seafaring men aware that the British Admiralty required British blue and red ensigns, with the national flag, the Union Jack in the place of honour, and the addition of a colonial symbol, took less than a week in September to select a design from some 30 000 entries. Essentially they chose the design of the Victorian red ensign with the addition of a large star—the Commonwealth Star—beneath the Union Jack, its six points symbolising the federating colonies

Image 6: These were the two shipping ensigns chosen by naval and marine judges in 1901. Modified and approved by the British Admiralty, they were gazetted in 1903.

Criticism and uncertainty

Significant critics of the design, both in Barton’s Liberal Protectionist government and in New South Wales, thought the design was too Victorian. They wanted the federation flag: the St George cross with stars. Barton, who had persuaded the Australasian Federation League to adopt and promote that flag for the new Commonwealth, eventually decided to send that design, as well as the one selected by the judges, to the imperial authorities. Predictably, the Admiralty chose the design for the two ensigns. With minor modification, they appeared in the Commonwealth of Australia Gazette in 1903 as the Commonwealth Ensign (blue) and the Commonwealth Merchant Flag (red).

Later governments of Labor’s Chris Watson in 1904 and Andrew Fisher in 1910 were also unhappy with the design, wanting something ‘more distinctive’, more ‘indicative of Australian unity’. Barton’s government did not seem interested in using the blue ensign, grudgingly agreeing to fly it only on naval ships not forts. Richard Crouch, the youngest member of the House of Representatives, a lawyer from Victoria, continued to be the flag’s advocate, persuading the House of Representatives in 1904 to pass a motion insisting that the blue ensign ‘should be flown upon all forts, vessels, saluting places and public buildings of the Commonwealth upon all occasions when flags are used.’ Watson’s government agreed to fly the blue ensign on special flag days, such as the monarch’s birthday, on Commonwealth buildings in Melbourne and Sydney, and on post offices, but not if it meant additional expense—a provision which undermined the decision.

Gradual adoption of the blue ensign by the Commonwealth government

But gradually governments began using the blue ensign: on forts in 1908 and as a saluting flag at reviews and ceremonial parades in 1911. Both Liberal and Labor governments under Alfred Deakin and Fisher used the blue ensign to mark their moves for greater Australian control over defence, especially the development of an Australian army and navy. Both hoped that Australian warships would fly an Australian, rather than British white ensign at the stern, a view Britain rejected. Australian governments also found that the Union Jack was still required at reviews where vice-regal representatives were present. Both blue ensign and Union Jack had to be used. Authorities took some time to adjust to the blue ensign being used. Australian patriots were annoyed in 1913 to see that the blue ensign was not used at the review in Fremantle of the men of the Melbourne, the first cruiser for the Royal Australian Navy to arrive from Britain. The government had to remind officers of the 1911 order.

As to the Commonwealth merchant flag or Australian red ensign, difficulties with proposed navigation legislation meant that commercial ships in Australia registered as British ships under Britain’s Merchant Shipping Act 1894 were not yet required to fly it.

The impact of war

Popularising the ensigns

Australia entered the war with three flags representing its dual nationality: the Union Jack as national flag and its two Australian ensigns. All three featured in recruiting drives for the Australian Imperial Force (the AIF). But the Union Jack was clearly regarded as the most important: ‘the’ flag, the artist James Northfield called it in his poster for the Victorian State Recruiting Committee.

Image 7: The Union Jack as the national flag, and the red and blue Australian ensigns were

used on recruiting posters during World War I

From Gilgandra in New South Wales a group of recruits, the ‘Cooees’ marched to Sydney late in 1915 carrying the Australian red ensign and the Union Jack. From Delegate in the south, the men from Snowy River carried an Australian red ensign, stitched by their women onto a larger British red ensign, in a recruiting march to a depot in Goulburn in January 1916.

Image 8: The Australian red ensign, seen here in a recruiting banner at Queanbeyan in 1916, was more common than the blue one

On troopships some took a red ensign with them, others the Union Jack. Australian ensigns, some presented by women’s groups from home, identified Australian casualty clearing stations and general hospitals at the front. In battle, there were occasional accounts of Australian ensigns marking objectives reached: either a tiny paper flag stuck in a tin of bully beef received in a parcel from home; or a blue ensign sent by the commander of the AIF as an incentive to the men taking a town.

On the home front the achievements of the Australians at war inspired a greater awareness of the Australian nation and a pride in its ensigns. As Charles Bean, the official historian, put it in a book for young Australians in 1918, those achievements ‘made our people a famous people … so famous that every Australian is proud for the world to know that he is Australian.’ In New South Wales state schools were now free to fly an Australian flag instead of the Union Jack, as had long been the case in Victoria.

Reinforcing the Union Jack

Although Australia’s role in the war popularised Australian ensigns, war and post-war conditions also circumscribed their use. The Union Jack retained its pre-eminence as the national flag on memorials, honour boards and fundraising badges, as well as in state schools.

Image 9: World War 1 badges

In South Australia from 1916 state schools were not allowed to fly an Australian ensign instead of the Union Jack, reflecting the suppression of its large German-speaking minority and the closure of their Lutheran schools. Their children, insisted John Verran, Labor MP, must be ‘taught by those who are British, and taught what it is to be British’. Under Labor, ‘I love my country’ became ‘I love my country, the British Empire’, in the words accompanying the salute of the Union Jack.

Throughout Australia the conscription campaigns of 1916 and 1917 made loyalty to Britain a key issue. The slogan ‘Australia first and the Empire second’ used by its most outspoken advocate, Irish-born Dr Daniel Mannix, Catholic Archbishop of Melbourne, in opposing conscription, exacerbated religious and ethnic division, especially with the failure of the second referendum. In 1920, when Mannix used Australian flags instead of the Union Jack in an extraordinary St Patrick’s Day procession in Melbourne, Protestant loyalists professed outrage. Forbidden to use Irish republican flags in the midst of the bitter Anglo-Irish war, and refusing to use the Union Jack, Mannix found Australian flags usefully ambiguous. They made the procession appear both loyal and disloyal at the same time: loyal, because organisers could answer critics by pointing to the Union Jack on the Australian flags; disloyal, because there was no separate Union Jack.

In such a context, Victoria’s Director of Education refused to adopt a suggestion that schools should use an Australian flag to mark Anzac Day, the ‘nation’s birthday’: ‘Teachers are at liberty to use either the Union Jack or the Australian Flag’, he responded, ‘but to prescribe the exclusive use of the latter might prove a welcome reinforcement to the propaganda of disloyalists.’

Labor’s split over the issue of conscription and the re-alignment of political parties saw Labor become more strongly Irish-Catholic in orientation and the Nationalists more militantly English-Protestant. In New South Wales, Labor’s links to not only Irish republicanism but also another anti-British movement, international communism, made Labor’s promotion of an Australian ensign rather than the Union Jack suspect in the eyes of the wider community. Nationalists prided themselves on representing that community, in contrast to what they portrayed as Labor’s sectional and disloyal interests. In the volatile politics of the post-war period Nationalists made much of the Union Jack in appealing to voters, especially returned soldiers. In this they had the support of the Returned Sailors’ and Soldiers’ Imperial League of Australia (the RSL) and other conservative groups like the King and Empire Alliance. An Australian ensign, unless accompanied by the national flag, the Union Jack, was seen as a disloyal symbol.

Was the blue ensign the national flag?

Questions of precedence and protocol

The Nationalists’ requirement that the Union Jack should always accompany an Australian ensign saw the issue of precedence played out very publicly on the flagpoles of Sydney’s Town Hall in 1921. Should the Union Jack have precedence? Much political point-scoring prompted a barrage of questions to the Department of the Prime Minister. There was a related question: was the blue ensign on shore for Commonwealth government buildings only? In essence both questions were really about which flag was the national flag: the Union Jack or the Australian blue ensign?

During the interwar period, these questions were a constant source of frustration for public servants in the Department of the Prime Minister, with little involvement of their political masters. But by 1924 there was agreement that the Union Jack should take precedence as the national flag. The blue ensign was for Commonwealth government buildings, but could be used on state government buildings if the state ensign was not available. There were no restrictions on the red ensign or the Union Jack: these were the flags state schools, private organisations and individuals could fly.

It was not surprising, then, that British flags took precedence over Australian ones on Parliament House, Canberra at its opening by the Duke of York in May 1927. What was surprising were the red rather than blue ensigns decorating the building, if we are to believe the commissioned painting of the event.(see Image 10, below) Surely the Commonwealth’s most important public building would be decked out in blue ensigns—the Commonwealth government’s flag. The artist, Septimus Power, known for his ability to ‘create a feeling of movement and drama’, may have painted the ensigns red for dramatic effect—to highlight the St George crosses in the Union Jacks, and the carpet leading from the Duke’s carriage to the main entrance. Or was it to underline the red ensign as the Australian flag people could use?

Image 10: Harold Septimus Power, ‘The Arrival of Their Royal Highnesses the Duke and

Duchess of York at the Opening of Federal Parliament House Building,

Canberra, 9 May 1927’ (1928)

Victoria forces the Commonwealth’s hand

Late in 1940 the Victorian government challenged the assumption that the blue ensign was for governments and not people by passing legislation allowing state schools to buy that ensign. Albert Dunstan, the shrewd Country Party radical who governed Victoria with Labor’s support, had finally tired of waiting nearly two years for the prime minister to respond to his request to end restrictions on the blue ensign or release a statement allowing schools and the general public to use that flag.

His legislation had the desired effect, prompting one Sydney newspaper to declare that ‘the red Australian flag, most often flown is not the real Australian flag’. Robert Menzies, leader of the United Australia Party government authorised a statement in March 1941 permitting Australians to use either ensign on shore. Ben Chifley’s Labor government issued a similar statement in 1947. But widespread press disinterest meant that questions from the public continued.

Changing the national flag

An Australian flag for every school

In December 1950 the Menzies government decided that the blue ensign should be proclaimed the national flag, enabling organisers of the jubilee celebrations to present it to every school. Legislation followed in 1953, with Queen Elizabeth II giving her assent while in Canberra in February 1954. The Australian flag now took precedence over the Union Jack.

Accepting the change

Australians took some decades to understand and accept the change that had taken place. South Australia’s Director of Education suspected that the Commonwealth government intended its gift of 1951 to replace the Union Jack in state schools’ national salute. South Australia chose to continue with the Union Jack, even after 1954. Only in 1956 could school principals there choose to use the Australian national flag instead of the Union Jack. Even in the 1970s many Australians persisted in regarding the Union Jack as the national flag, which explains Arthur Smout’s campaign from 1968 to 1982 to urge Australians to give the Australian flag precedence.

Promoting the Australian flag

Menzies promoted the Australian national flag by having it flown every day above the entrance to Parliament House from 1964, and from government buildings on working days. The National Capital Development Commission, created by the Menzies government in 1958, erected two huge flagpoles for Australian flags on Capital Hill and City Hill.

The federal government’s practice of giving flags to schools widened to include youth groups and by the 1970s national sporting bodies. By 1980 the Australian flag had been placed in the House of Representatives and become part of the logos of the two major parties. The flag was central to the brief prepared for entrants in the Parliament House design competition of 1979, and to the winning design. Its flagpole dwarfed the previous one on Capital Hill and even more so the short central flagpole on Parliament House below it. The image became an Australian icon.

Even so, Malcolm Fraser’s Coalition government, when establishing the long-awaited Australian shipping register in 1980, could not persuade Australia’s merchant marine to adopt the Australian national flag instead of the Australian red ensign, affectionately known as the red duster.

Questioning the design

Just as most Australians had come to accept the Australian blue ensign as their national flag, a growing percentage of them felt that it was not really Australian, dominated as it was by the flag of another country. It was essentially a British ensign. Indeed Australia still had two British ensigns, as it had in 1903 when the Union Jack was the national flag. Morgan Polls showed the percentage of Australians wanting a new flag increasing from 27 in 1979 to 42 in 1992, to a majority of 52 in 1998.

The emergence of two lobby groups, Ausflag in 1981, determined to find a more appropriate design for an Australian flag, and its counterpart in 1983, the Australian National Flag Association, equally determined to prevent change to the flag, began an increasingly serious contest for the hearts and minds of Australians. Almost as serious was a similar contest between Labor Party governments under Bob Hawke and Paul Keating and the Liberal-National Party Opposition. By the mid-1990s the Australian flag, or the Union Jack on it, was disappearing from the logos of national organisations, such as the National Australia Day Council, Ansett Australia, and the Australian Labor Party.

Discouraging change

Since 1996, the Coalition government under John Howard has discouraged discussion about change to the flag by establishing Australian National Flag Day in 1996, legislating in 1998 to make change more difficult for governments, reproducing the Australian National Flag Association’s promotional video on the flag and putting it into all primary schools in 2002—at a time when the Australian community was so divided over the flag; providing a subsidy to all schools for erecting a flagpole in 2003, and requiring all schools receiving federal funds to fly the Australian flag in 2004.

Two Questions

Why did the transition from Union Jack to Australian national flag take more than fifty years?

Governments’ reluctance

For several decades from 1901 Australian governments struggled to understand the symbolism involved in the Commonwealth being a self-governing not an independent state within the British Empire. Barton’s government, which favoured the federation flag over the competition design, seemed to ignore the fact that the British Admiralty required two shipping ensigns, the red and the blue ensigns, not the federation flag as the national flag. Once the ensigns were gazetted, the government naturally hesitated to use the blue ensign on forts as if it were the national flag. It clearly wasn’t, as the Defence Department insisted. It was an ensign of the national flag, the Union Jack.

The war brought to the fore this issue of whether the blue ensign was the national flag. People and governments—state and local—wanted to use Australian ensigns for patriotic purposes on land. But which should they use? Neither the Prime Minister’s Department, bombarded with questions from the public and responsible for advice on the issue, nor the more conservative Defence Department, seen to be the source of expertise, was sure. The Nationalist government was unwilling to sort out the issue. The press was disinterested. Public uncertainty dragged on into the 1930s.

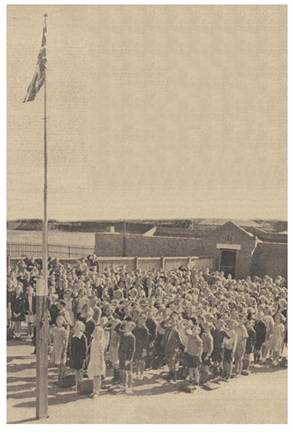

Image 11: Children of Brighton-rd State School, Melbourne, salute the Union Jack in 1938

Albert Dunstan, the Victorian Country Party premier who in 1940 allowed state schools to buy blue ensigns from flag suppliers, was unusual in his grasp of the issue and his determination to solve it. For patriotic purposes, he argued, the blue, not the red, ensign should be used by governments and people. But Menzies, more cautious despite receiving advice which confirmed Dunstan’s opinion, chose instead to announce in 1941 the end of restrictions on the flag’s use. He feared that declaring the blue ensign to be the national flag would raise awkward questions about the Union Jack in the midst of war.

Such considerations continued to matter. Labor prime ministers were usually even more cautious, wary of the anti-British tag so easily pinned on them by non-Labor. Chifley issued a similar statement to Menzies in 1947, but went further in referring to the blue ensign as ‘the national emblem’ rather than as ‘a national emblem’. Two years later he established an interdepartmental committee to consider a range of issues relating to flags. One of them was whether an ensign could be a national flag. There was some support in the Prime Minister’s Department for a new flag, the design of Australia’s ensigns being seen as perpetuating Australia’s ‘colonial status’. With the Union Jack in the corner the flag could not be ‘truly Australian’. However, the committee recommended that the blue ensign should be proclaimed as Australia’s national flag, since it had been used on the jackstaff of Australian warships since 1911 and was the flag preferred in the Menzies statement of 1941.

But the proposal which brought this recommendation to Cabinet came from a departmental committee planning the jubilee of federation celebrations: the presentation of a blue ensign to every school. Perhaps its chairman, the head of the prime minister’s department, saw the jubilee as a rare opportunity to establish the blue ensign as the Australian flag—especially since the press took so little notice of his department’s statements over the years to establish it as such. When a state director of education queried the choice of ensign, Menzies as the new prime minister took the issue to Cabinet. Organisers doubted that 10 000 flags could be made and delivered to schools by May 1951 as other issues—including the war against North Korea—took precedence on Cabinet’s agenda. But finally Cabinet made the decision early in December 1950.

Government reluctance to negotiate sensitive matters of symbolism still mattered in 1953. When Menzies introduced the Flags Bill to have the blue ensign designated the Australian national flag, he hid the change taking place, explaining that the legislation would make ‘no change’. That was not true. He reassured those attached to the Union Jack that it would still fly beside the Australian flag, and that the Act guaranteed Australians’ right to fly it. But he did not explain that the Australian national flag would now take precedence over the Union Jack. Further reassurance was the Queen’s assent to the Act given in Canberra in February 1954.

Governments’ promotion of the Australian flag over the next three decades eased the transition from British to Australian national flag, as did the fact that the Australian flag still carried the Union Jack in the place of honour—a legitimising symbol.

But how were governments going to respond to the possibility of a further transition: the removal of the Union Jack from the national flag? Only in early 1992, after the ALP had dropped its policy of flag change, did Paul Keating’s Labor government tackle the issue: ‘We can fly two symbols of our nationhood no longer’, was Keating’s view. But with no obvious alternative flag design, and as the target of campaigns by the RSL and its offshoot, the Australian National Flag Association, and the Coalition, the Labor government dropped flag change in mid-1994 to avoid compromising its move to a republic.

The John Howard Coalition government’s amendment to the Flags Act in 1998 was unusual in attempting to prevent future governments from changing the flag without a national vote. Previous governments had been free to make such changes to national symbols: as Labor’s Andrew Fisher in 1912 had in changing the coat of arms; Menzies, in changing the national flag in 1954; and Hawke in changing the national anthem in 1984. Curiously, the passing of the amendment against flag change in March 1998 occurred just as the Morgan Poll revealed that a majority of Australians wanted a new flag.

Dual national identity

Governments’ reluctance to explain the changing symbolism of Australia’s national flags reflects Australians’ history of a dual national identity. Until recent times, most Australians saw themselves as Britons as well as Australians. They belonged to two nations. Henry Parkes, often called the father of federation, had urged the Australian colonies in 1890 to federate because of the British background they shared—‘the crimson thread of kinship’, he called it. But Australians’ vote for federation also represented Australians’ desire to be a nation.

In state schools after federation we see the tension between these two identities in the school ritual of saluting the flag. Sir Frederick Sargood, a respected politician from Victoria and soon to be a Senator, had introduced the Union Jack into schools in 1901, supposedly to celebrate the opening of the first Parliament, but really to remind future generations of Australian children that they were British. Saluting that flag became an established ritual. Sir Frederick feared that in becoming an Australian nation, Australians would forget that they were British. The introduction of Empire Day in 1905 further bolstered the ritual, again reinforcing the British connection. Prompted by the British Empire Union, also known as the League of Empire, conservative premiers and prime minister saw Empire Day as an opportunity to turn the electorate against a growing Labor Party which talked of developing Australia as a self-reliant socialist community.

What place would there be in schools for an Australian flag, especially given Australians’ emotional attachment to the Union Jack as the flag of freedom and strength? South Australia provides an extreme example of how difficult finding that place was, even in the 1950s, where country was still defined as the British Commonwealth, not Australia.

Menzies maintained a strong sense of a dual nationality in reflecting on the first fifty years of federation. The Canberra Times reported him as saying in May 1951:

In those years Australia became a really well-knit nation, and we became Australians … We are Australians and we must thank God for that. In our 50 years there has never been argument about whether we are British or not. We are British.

By that time the Chifley government in the Australian Nationality and Citizenship Act of 1948 had formally defined the status of Australian citizenship, although Australians continued to be British subjects until 1984.

A vulnerable society

Not only sentiment but also fear tied Australians to the Union Jack. Sir Frederick gained support for putting that flag into schools in 1901 because of the heightened imperial sentiment during Australia’s involvement in the South African war. Most Australians saw British ties as essential to their defence. They were only too conscious that the small egalitarian European society they were creating in this vast continent on the edge of Asia far from ‘home’ depended on the Royal Navy keeping at bay other European powers and, from 1905, expansionist Japan. Australia’s ties with Britain, at the centre of the dispute over conscription during the First World War, became even more important to Australia in an insecure post-war world. The wearing of British ensigns by the Royal Australian Navy from 1911 and the Royal Australian Air Force from 1922 at Britain’s insistence underlined that fact.

At imperial conferences after the Great War Australian governments discouraged calls by Canada, South Africa and Ireland for Britain to recognise their independence. When those calls led to such recognition in the Statute of Westminster in 1931, Australia chose not to ratify it until 1942. The closer Australia’s ties to Britain, Australian governments argued, the more likely Britain would defend and promote Australian interests.

That view became increasingly impossible to maintain, as Labor Prime Minister, John Curtin, and later Robert Menzies recognised in seeking alliance with the United States. That the decision to present the blue ensign to all schools in 1951 was made in the midst of the Korean War is significant—a recognition that children must increasingly be taught to be Australian, rather than British. The Vietnam War, in which Britain was not involved, emphasised the point. From 1967 Australian warships no longer flew the British white ensign but an Australian one. The RAAF had already made that transition in 1949.

By the mid-1980s Australian governments found it easier to separate British and Australian sentiment and interests. But since then polls and competitions revealing the strength of calls for change to the flag, in particular removing its Union Jack, sparked a reaction by the more conservative, troubled by economic change and the changing ethnic composition of Australian society. The assumption that only those of British or European stock were Australian resurfaced. The Australian flag became a British symbol. By 1997 Pauline Hanson of One Nation fame was wrapping herself in it. In response, the Howard Government, encouraged by the Australian National Flag Association, promoted the flag ever more zealously, especially amongst the young from 2002 to 2004, ignoring the strong and continuing division among Australians over its Union Jack. Again, war—in Afghanistan and Iraq – made its task easier, patriotism in schools becoming the preserve of the federal rather than state government. The expansion of the number and size of private schools—including Islamic schools—encouraged by the Howard government, now required the flying of the Australian flag if they received federal funds.

In more recent times young people have begun wearing the flag at sports events and at Gallipoli, and, more worryingly, using the flag as a weapon. Australian flags at the centre of the riots at Cronulla Beach in in December 2005 and at the Big Day Out in January 2006 challenged sociologists, psychologists, anthropologists and historians to explain their meaning. Wearing the national flag had become more than simple exhibitionism to catch the eye of the TV camera crews. In those contexts the flag represented ethnic chauvinism at the heart of Australians’ sense of vulnerability.

Why is so little known about the transition in national flag from Union Jack to Australian national flag?

The reluctance of governments between 1901 and 1954 to explain to Australians the relationship between the Union Jack and its ensigns left both governments and people uncertain about the history of the blue ensign. After 1954, when it became the Australian national flag, replacing the Union Jack, governments presented it as the uncontested national symbol since 1901.

The flag certificate accompanying the blue ensign into schools in 1951 introduced it as ‘this symbol of our unity and nationhood’ since 1901, the flag’s Union Jack showing ‘Australia’s link with Britain’. Effectively its text hid the role of the Union Jack as the national flag and the role of the red ensign as the people’s flag, making it appear that the blue ensign had always been the national flag. In several editions of the booklet on the national flag based on the certificate, governments have continued to hide that history.

Yet the booklets reveal clues to a very different history from the one they presented. Why was it necessary to assure Australians until the 1970s that they were allowed to fly the Australian national flag and the Union Jack? Why until the mid-1980s did they include illustrations showing how to correctly fly or display the two flags together?

We need to explore and enjoy the flag’s history in all its complexity. Hiding it leaves governments and people vulnerable to misinformation and mythmaking.

Question — At the outset you showed a photograph of the British coat of arms and the Australian coat of arms on doors in Old Parliament House. Now I may be wrong but I think I counted seven points on that star. Why are there seven when we have six?

Elizabeth Kwan — The Commonwealth Star on the Australian coat of arms of 1908 and again of 1912 had seven points: six for the federating states; and a seventh point for Australian territories after Australia became responsible for Papua in 1906. The Australian ensigns, gazetted in 1903, had had a six-pointed Commonwealth Star. It gained a seventh point in 1908 to be consistent with the seven-pointed star in the first coat of arms approved earlier that year.

Question — I would like to congratulate you on putting in front of us a wonderful picture.

What about the Celtic fringe, the Scots, the Welsh and the Irish, who were the foundations of this country? What right did politicians have to decide on a flag for them, and where are these nations in it?

Elizabeth Kwan — Well, we were settled as a British settlement, and I think part of being British is that people wear several different hats. The Welsh and the Scots and the Irish saw themselves as individual nations, but they also wore a British hat. Within Australia, people are wearing all kinds of hats all at the same time, but in different contexts. So I think that’s really the issue we’re wrestling with here.

Question — Dr Kwan first of all, if we were so wedded in Australia to the Union Jack at the time of federation, why was a national competition held for a so-called Australian flag? Secondly, following up on the first question today, why does the Southern Cross design have on its stars five, six, seven, eight and nine different points as you go around the Southern Cross?

Elizabeth Kwan — As Canada had its two shipping ensigns, so Britain expected Australia to have two ensigns. These were to be ensigns of the Union Jack, which continued to be the national flag. The national competition was to determine the colonial symbol on the ensigns.

The design of the two ensigns selected from the competition gave the stars of the Southern Cross five, six, seven, eight and nine points to indicate the varying brightness of the five stars in the constellation. But the Admiralty modified that design by giving all stars seven points, except the smallest which had five. And it also refined the shape of the Commonwealth Star.

Question — When I was at school, which was during the Second World War, and we put up the Union Jack first of all, it was sacred and you must never let the flag touch the ground. I’m amazed at what people do with the flag now. They wrap themselves in it, they paint themselves with it. So I’m wondering has your study touched on that aspect of it?

Elizabeth Kwan — It’s a good point and it’s one that I think concerns us today. I wonder, for example, how the Australian National Flag Association, which keeps pushing this flag, feel about the way people are treating it because of course, the flag should never touch the ground. There is a flag company now that is making flags as capes, so they are catering for this new demand to wear the flag without it touching the ground.

I think there is a strong element of exhibitionism in this use of the flag, but if we are speaking of Cronulla in 2005, of course it was much more than that. I felt that people were staking out their ground, and I think that this relates to their sense of vulnerability—they feel that they are being invaded by non-Australians, and they have this idea that to be Australian you must be British in background, or at least European. I think that attitude has resurfaced and is actually being verbalised now since Pauline Hanson. A lot of people still assume that in the way they use language; not always necessarily in an offensive way, although of course it is offensive to those who are not from a European background.

Sources of Images

Image 1

Auspic

Image 2

Elizabeth Kwan

Image 3

Film World and Cinesound Movietone Productions, from the collection of the National Film and Sound Archive, a division of the Australian Film Commission

Image 4

Film World and Cinesound Movietone Productions, from the collection of the National Film and Sound Archive, a division of the Australian Film Commission

Image 5

Senate Resource Centre

Image 6

Ralph Kelly

Image 7

‘Were You There Then?’ National Library of Australia nla.pic-an14107674

‘Come On Boys–Follow the Flag’, courtesy of the James Northfield Heritage Art Trust

‘Oppression/freedom’, South Australian State Recruiting Committee Poster, State Records of South Australia GRG 32/16/33

Image 8

Australian War Memorial Negative Numbers REL/15959 and P01095.001

Image 9

World War I badges ca. 1914–1920, courtesy of the State Library of South Australia, SLSA PRG 903.

Image 10

Historic Memorials Collection as part of the Parliament House Art Collection, courtesy of the Department of Parliamentary Services, Canberra, ACT

Image 11

Age, 16 February 1938

* This paper was presented as a lecture in the Senate Occasional Lecture Series at Parliament House, Canberra, on 4 May 2007. Those interested in the detail documenting the paper will find it in Elizabeth Kwan, Flag and Nation: Australians and Their National Flags since 1901. Sydney, UNSW Press, 2006.

[1] It is flag protocol that the flag on the viewers’ left when facing a building is in the position of honour.

Prev | Contents

Back to top