Peter Mares

With six million people or 27 per cent of the population born overseas Australia has—apart from the city-states of Singapore and Hong Kong—the highest proportion of overseas-born residents of any country in the world.[1] This reality is so entrenched, so normal, so much a part of our daily lives, that we rarely stop to consider how migration works and how it might be changing; to ask whether migration today is the same as it was ten, twenty or thirty years ago.

Of course we have an acrimonious debate about how to respond to asylum seekers arriving by boat, but that is a question of refugee protection and border control rather than migration. Important and politically fraught as the issue is, the arrival of asylum seekers by boat has only a small impact on the future shape of Australian society.

In terms of population size and demographic mix, migration is the main game and skilled migration is the increasingly dominant component in the mix.[2] The thrust of my argument in this lecture is that Australia's migration program is changing in quite fundamental ways. In fact we may be witnessing the biggest change since the abolition of the White Australia policy forty years ago, but these changes are not widely recognised or discussed. The implications of these changes are not entirely clear or predictable, but they may well be profound.

Let's start with multiculturalism.

In February 2011, the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship, Mr Chris Bowen, gave a speech on 'The genius of Australian multiculturalism'. It was an interesting speech, inasmuch as it sought to reclaim the language and the values of multiculturalism in political discourse after many years in which the M-word was either studiously avoided by our elected representatives or replaced with formulations, such as 'cultural diversity'.[3]

What interested me about the speech, however, was the way in which the minister sought to define Australian multiculturalism as being substantially different from other apparently failed models around the world. He said that Australian multiculturalism was distinguished from other varieties in three important ways.

The first distinguishing feature of Australian multiculturalism is 'political bipartisanship' which puts the policy 'above the fray of the daily political football match'.[4] Whether this is entirely accurate—particularly in recent years—is a matter for debate, but it is not the concern of this presentation.

A second element of the genius of multiculturalism in this country is that it is 'underpinned by respect for traditional Australian values'. Chris Bowen quoted former Prime Minister Paul Keating to illustrate his point: multiculturalism imposes a responsibility of loyalty and 'the first loyalty of all Australians must be to Australia, that they must accept the basic principles of Australian society'. These principles include 'the Constitution and the rule of law, parliamentary democracy, freedom of speech and religion, English as a national language, equality of the sexes and tolerance'.[5]

In another context, one might argue about whether Australian values are really substantially different from Italian values or American values or the values that underpin any other liberal democracy, but again I'll leave that matter aside.

I do, however, want to emphasise a phrase in the Keating quote: he said the first loyalty of all Australians must be to Australia and the basic principles of Australian society.

'Of all Australians': that raises a question, which I would like you to bear in mind during the course of this presentation—what about 'non-Australians' who live in this country on a long-term basis? There are an increasing number of non-Australians who live amongst us; people who are neither citizens nor permanent residents. Do we have a call on their loyalty? If so, what do we offer them in return? What is the reciprocal basis on which such an expression of loyalty might be expected?

The third element of the genius of Australian multiculturalism identified by Minister Bowen—and the most important for my purposes today—is that Australian multiculturalism is 'citizenship centred'. He points out proudly that Australia has one of the highest take up rates of citizenship in the OECD.[6]

This sets Australia apart from 'some countries in Europe … where people arrive from overseas as guest workers with little encouragement to take out citizenship … [and] … little incentive to become full, contributing members of that society'. The minister warns that such guest worker arrangements 'can lead to a complex and entrenched social cohesion dilemma'. Fortunately, in Minister Bowen's view, we are spared such risks because Australia is 'not a guest worker society'. Rather 'people who share respect for our democratic beliefs, laws and rights are welcome to join us as full partners with equal rights'.[7]

The minister is drawing here on the experience of migration to Australia in the second half of the 20th century. For much of that period, migrants arrived by ship and were often called 'New Australians'. However much that expression was used to set recent migrants apart as different (with particular reference to non-British migrants) this terminology nevertheless indicated that a move to Australia was considered permanent. This is not to deny that significant numbers of migrants ultimately decided not to stay in Australia or stayed without taking out Australian citizenship, but serves to emphasise that in this period there were relatively few options for temporary migration to Australia, let alone anything that might have been termed 'guest work'.

But in 2011 can we say as definitively and with as much certainty as Minister Bowen does, that Australia is not a guest worker society? Certainly Australia still has a large and substantial permanent migration program, but I will argue that old postwar model conjured up by the minister's words has now been superseded. While it has not been replaced with a 'guest worker' system per se, temporary migration—including temporary migration primarily for work—is now a permanent feature of the policy landscape.

My thesis is that our analysis has not caught up with this changed reality and we need to start thinking critically about what this might mean for Australian society—for multiculturalism and indeed for the particularities and peculiarities of our liberal democracy.

Forms of temporary migration.

Who are these 'non-Australians' who live and work amongst us? There are more than one million of them, so they account for almost five per cent of the total population.[8] As I said, they are neither citizens nor permanent residents, but they reside in Australia lawfully, on a long-term basis and with work rights. I have tried to invent a snappy acronym to describe them—a term that encapsulates their contingent status in Australia—simultaneously long-term and temporary. I came up with 'long-temps' but that makes them sound like replacement office staff. I also thought of 'tempi-dents', but that conjures up images of artificial teeth.

So I will stick to describing and differentiating them by their visa status, which is the most accurate way to proceed, since this is in fact a diverse population that cannot be easily lumped together.

They fall into four main categories: working holiday makers, international students, skilled workers on temporary 457 visas and New Zealanders. Not all of these people would be working. Some are children, some are stay-at-home spouses and some are students fully supported by scholarships or by their families overseas. Some work intermittently, like backpackers supplementing their savings so they can stay on the road longer, or students working only in semester breaks. Nevertheless, collectively these four groups now account for about ten per cent of the total workforce. Since they are on average much younger than the general population, their role in the labour market is particularly pronounced in certain age brackets. A calculation prepared by the Department of Immigration and Citizenship concluded that working holiday makers, skilled workers on 457 visas and international students now make up around one fifth of the total labour force aged between 20 and 24.[9] If you included New Zealanders in this calculation then the proportion would be even higher.

So let's take a closer look at the four main categories of temporary residents with work rights, beginning with working holiday makers.

Working holiday makers.

The Working Holiday visa is valid for 12 months and open to travellers aged 18–30 from 19 countries or territories with which Australia has a reciprocal relationship.[10] More restrictive reciprocal 'work and holiday' arrangements are in place with seven other countries.[11]

The Working Holiday scheme is intended to 'encourage cultural exchange and closer ties … by allowing young people to have an extended holiday, and supplement their funds with short-term employment'.[12]

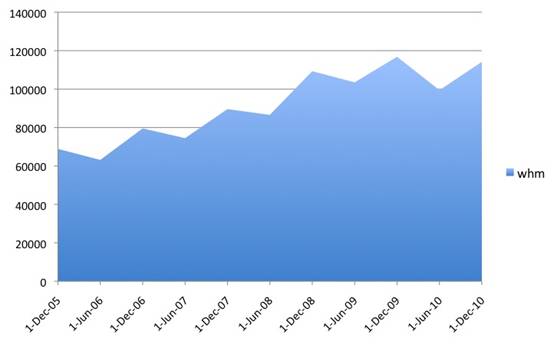

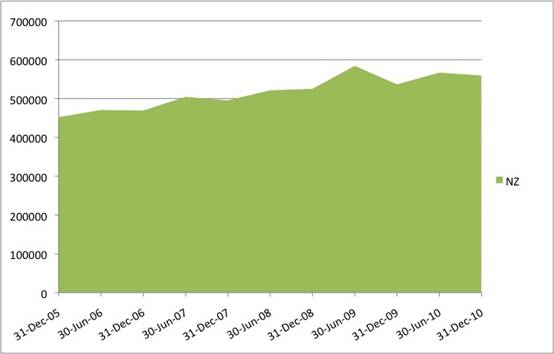

Chart 1: Working holiday makers (stock) 2005–10

The take up of the scheme has grown steadily and the number of working holiday makers present in Australia at any one time has risen by 66 per cent in the five years from 2005 to 2010 (chart 1), up from around 69 000 (68 867) to more than 114 000 (114 158).[13] The two largest source countries for working holiday makers are the UK and South Korea, which between them account for about 40 per cent of the visas issued each year, followed by Germany, France, Ireland, Taiwan, Canada and Japan, which make another 45 per cent of the visas issued.

Most working holiday makers probably spend more money in Australia than they earn during their trip; the median length of stay is 209 days and the vast majority depart Australia before their visas expire. The program helps to promote tourism. It is also a reciprocal scheme that affords similar opportunities to young Australians who travel overseas. So I am not suggesting that there is anything inherently wrong with the working holiday maker scheme, that it is bad policy or presents a major problem.

However, looked at from another perspective, the scheme has been increasingly instrumentalised by government to address labour market issues. For example, working holiday makers are now eligible for a second 12-month visa if they undertake at least three months of 'specified work' in an 'eligible regional Australian area'. Initially this was done to encourage travellers to help meet labour shortages in seasonal agriculture, particularly during fruit and vegetable harvests. However the list of industries that qualify as 'specified work' has been repeatedly extended and now includes plant and animal cultivation, fishing and pearling, tree farming and felling, mining and construction.[14] Similarly, the list of 'designated regional areas' is a long one, and essentially covers all of Australia apart from the ACT and eight major urban centres (Sydney, Wollongong, Newcastle, the NSW Central Coast, Melbourne, Brisbane, the Gold Coast and Perth).[15]

Also working holiday makers mostly enter the job market at lower wage rates and their profile in the labour force is 'clearly biased towards lesser-skilled jobs'.[16] An unpublished departmental survey found that the most common jobs held by working holiday makers were farmhand, waiter, cleaner, kitchen hand and bar attendant, accounting for about 60 per cent of all the jobs undertaken.[17] In the same survey, more than a third of working holiday makers reported being paid at rates below the federal minimum wage (of $13.74 per hour at the time).[18]

There is evidence that the net employment effect of working holiday makers is positive—that their presence in Australia generates more jobs than they take up. But their significant numbers at the lower end of the labour market and their willingness to accept—or incapacity to resist—pay at rates below the legal minimum wage, nevertheless raises an interesting question: to what extent are these working travellers displacing locals who are 'in direct competition for the same kinds of work'?[19] The group most at risk of being displaced would be low skilled school leavers exiting the education system and entering the workforce for the first time. It is worth remembering that despite Australia's strong economy, the unemployment rate is 15.6 per cent for 15–19 year olds and 10.2 per cent for 15–24 year olds (in July 2011).[20]

International students

Similar questions can be posed in relation to international students, the second major group of long-term temporary residents in Australia, who have the right to work up to twenty hours per week during term time and longer in semester breaks. Overall the net employment impact of international students is positive—they generate more jobs than they fill. However if you chat to a taxi driver or the person behind the counter at a late night convenience store or the waiter serving a meal in an Asian restaurant, it quickly becomes obvious that international students now constitute a significant proportion of the low status, casual workforce in the contemporary service economy. Again, there is a view—though not one I think has yet been convincingly proved or disproved—that international students displace local workers in this sector and exacerbated the problem of youth unemployment.[21]

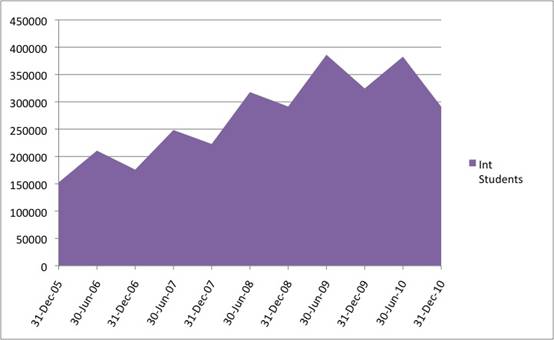

As with the other categories on temporary migrants, international student numbers grew rapidly during the first decade of this century before a sharp turn down in the past few years. Even after the fall in new commencements the stock of international students in Australia on 31 December 2010 was 90 per cent higher than five years earlier (291 199 compared to 152 622).

A number of factors contributed to the sudden drop in new overseas student commencements—the high dollar, highly publicised attacks on students (Indian students in particular), the global downturn and the changes to policy which essentially broke the nexus between study in Australia and permanent residency, removing a carrot that had drawn many students here in the first place. As has been well documented, when study and migration were directly linked under the Howard Government, this created perverse incentives and led to unintended outcomes, including an explosion of private training colleges offering vocational courses of sometimes dubious quality that promised the shortest possible route to permanent residency.

Chart 2: International students (stock) 2005–10

The link between study and migration contributed to a blow-out in valid applications for permanent residency. By 2009 the department had on hand 137 500 valid applications for independent general skilled migration. That is more than two years supply of migrants in that stream of the program, with 9000 new applications coming in every month.[22] The program was in danger of being overwhelmed.

One of the changes made to manage that problem was priority processing. Introduced from the beginning of 2009 and amended several times since, priority processing fundamentally changes the way in which applications for permanent residency are dealt with. Instead of applications being considered in the order in which they are lodged, as in the past, they are now sorted into five different categories in line with Australia's perceived economic needs. In descending order of priority these categories are:

1. Applicants sponsored by an employer under the Regional Sponsored Migration Scheme or applying for a Skilled–Regional visa (subclass 887)

2. Applicants sponsored under the Employer Nomination Scheme

3. Applicants nominated by agencies of state or territory governments for occupations listed on their respective migration plans

4. Applicants with an occupation on the new Skilled Occupation List (SOL Schedule 1 in effect from 1 July 2011)

5. All other applicants[23]

When he introduced priority processing former Immigration Minister Senator Chris Evans said the old system that served everyone in order was 'just like pulling a ticket number from the dispenser at the supermarket deli counter'.[24] It 'didn't make any sense', he said, that Australia was 'taking hairdressers from overseas in front of doctors and nurses'.[25] This may be true from a national interest perspective, but from the perspective of procedural fairness priority processing has had distressing outcomes for individual applicants. The changes were applied to visa applications that had already been lodged, with the result that tens of thousands of aspiring migrants are facing indefinite limbo. They are stuck in 'category 5'—the lowest priority group—and any new higher priority application entering the system is processed ahead of them. In effect it is like being at the back of a queue and never moving forward, watching helplessly as newcomers constantly join the line ahead of you.

There are 37 200 people currently resident in Australia who are in the priority 5 group—almost all of them former international students who have graduated from Australian colleges and universities. More than 10 000 (10 570) have already waited more than two years for their applications for permanent residency to be considered.[26] Let me be clear—these are people whose applications were valid at the time they were lodged—they had the professional qualifications, language skills, age profile, health and character checks to score high enough in the migration points test to qualify for permanent residency. But their applications have been put to the bottom of the pile and will remain there for the foreseeable future since all applications in the other four higher priority categories will always be processed ahead of them and new applications enter the system all the time.

The Department of Immigration and Citizenship wrote recently to members of this lowest priority group saying that it 'expects to commence processing of some priority group 5 applications in this program year'. However the same letter warned 'many priority group 5 applicants will still have a long wait for visa processing'.[27]

In the meantime, they live in Australia on bridging visas, with permission to work but without the right to travel overseas, unless they have a substantial reason to do so—such as the illness or death of a close relative, or to meet the requirements of their employer. Nor can they sponsor relatives to join them in Australia. The result is that wives and husbands are forced to live apart; couples planning to marry must postpone their wedding indefinitely. In some cases, parents must live apart from their children left behind with relatives while they completed their studies in Australia.

Those relegated to priority group 5 could of course give up their dream of permanent residence at any time and return to their countries of origin—but if they do so then they will forfeit the visa processing charge paid to the Australian Government (currently set at $2960), plus any other moneys invested in their application—potentially thousands of dollars in professional migration advice, and hundreds more in health checks, police checks, language tests and skills recognition. That is not to mention the amount that they have invested in an Australian education as full fee paying students or any emotional or psychological commitment they may have made to Australia as a nation.

Since I began reporting on this issue almost two years ago,[28] I have been in touch with scores of applicants from a broad range of backgrounds, including a Brazilian expert in international trade negotiations who speaks four languages fluently, a medical scientist from France engaged in cancer research, an aspiring Chinese entrepreneur with a law degree and masters in translation and interpreting, a Sri Lankan IT graduate working in the health industry, and a German anthropologist whose PhD was paid for by the Australian taxpayer and who is an expert in, of all things, refugee issues in Malaysia. I have also come across cooks and hairdressers—all of them employed and some hoping to establish their own businesses in Australia, if their visa uncertainty is ever resolved.

Let me just briefly outline two of their stories for you. Originally from China, Xiru Li submitted his application for permanent residency three years ago and is still waiting for an answer. He first came to Australia in 2002 at age of 17 and completed two years of high school, before studying a degree in business administration at Macquarie University and a masters in Business Law at the University of Sydney. Xiru Li estimates that his family invested at least $200 000 in his Australian education. He hopes to build a career in Australia in business or financial services but has found it hard to get a job in line with his qualifications while stuck on a bridging visa so Xiru Li works as a mortgage broker. Aged 27, Xiru Li has lived in Australia for more than a third of his life.

'Helen' first came to Australia on holiday. She liked the country so much that in 2006 she chucked in her office job in the UK, sold her house and moved her entire family to Australia to embark on a new career by studying hairdressing. She paid $10 000 in fees to attend a private college that turned out to be little more than a shop front. She complained to various authorities to little effect, left after six months and did not receive any kind of refund, instead investing another $17 000 at a different, more professional college. Helen has been constantly employed in salons since qualifying in her trade, but her application for permanent residency, lodged two and a half years ago, is the lowest priority for processing. When Helen arrived in Australia her son 'Nick' was 15 years old. Now he is 20. He has finished school but if he wants to study at a tertiary level he has to pay the full fees that apply to an overseas student. Nick has tried unsuccessfully to find an apprenticeship but employers are wary of taking him on because of his temporary visa status. Soon Nick will be 21 years old. That means he will no longer be considered as Helen's dependent for the purposes of her family's application for permanent residency. As a result he will have to apply for permanent residency independently, but he has neither the skills nor qualifications to succeed.

Xiru Li, Helen and other international student graduates stuck on the bottom rung of the priority processing list are at risk of becoming permanently temporary—living and working in Australia long term, contributing to our economy and our society, but kept at arm's length and unable to settle.

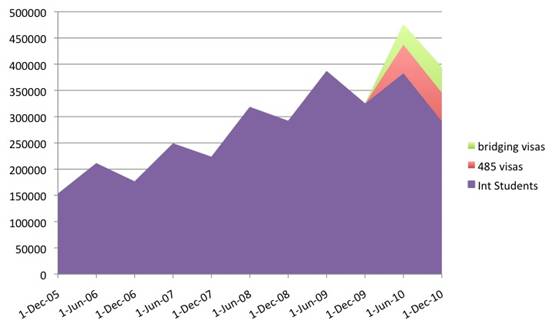

In addition to those on bridging visas and waiting for their permanent residency applications to be considered, there is another group of 62 000 international student graduates who have been issued with, or who have applied for 18-month long 485 Skilled–Graduate (Temporary) Visas.[29]

Chart 3: International students and student graduates and bridging and 485 visas

The Department of Immigration's published service standard for the processing of these 485 visa applications is 12 months.[30] A 12-month wait to be issued with an 18-month visa! These 62 000 graduates also aspire to permanent residency, but do not meet the criteria for skilled migration. In theory the 485 visa allows them to 'to gain skilled work experience or improve their English language skills'.[31] At the end of the 18 months, some may meet the criteria, others will not. In the meantime, like their contemporaries in priority group 5, they live and work in Australia on a temporary basis, paying taxes but ineligible for most government benefits, excluded from voting or running for office, and with no formal representation at any level of our political process.

457 visas

The third category of long-term but not permanent residents with work rights can be more correctly identified as temporary migrant workers—they are skilled workers on 457 or 'business (long-stay)' visas.

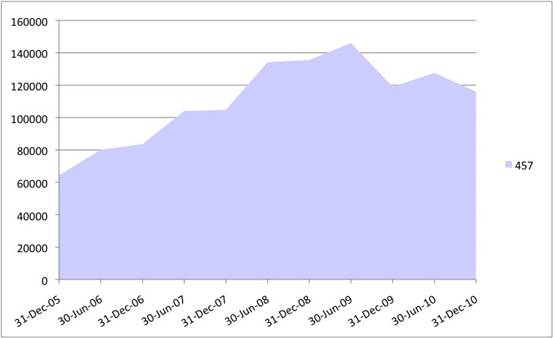

Conceived under the Keating Labor government and formally introduced soon after John Howard led the Liberal–National Party Coalition to power in 1996, the 457 visa was initially intended to be a transitional measure to fill temporary skills gaps in the Australian labour market until the domestic education and training system could catch up with demand. But in the years after it was created, use of the 457 visa category grew dramatically. Although numbers fell back during the global financial crisis, the stock of 457 visa holders in the country in 2010 was still almost double that of five years earlier (up from 64 340 to 116 012) (chart 4).

Chart 4: 457 visa holders in Australia (stock) 2005–10

There was a sharp increase in new 457 visas issued last financial year (2010–11 up 34 per cent year-on-year). If this trend continues then the annual temporary skilled migration intake may soon overtake the annual permanent skilled migration intake, as it did once before 2007–08, since permanent migration is subject to an annual cap and temporary migration is not (chart 5).

Further growth in temporary skilled migration will be encouraged by recent changes to government policy.

In the 2011–12 federal budget the government committed an extra $10 million in the administration of the 457 program to set up a new processing centre in Brisbane with the aim of cutting down the median processing time for 457 visas from an already speedy 22 calendar days to just 10 days.[32] It is a stark contrast to the 12-month processing time for student graduates applying for a 485 skilled graduate visa, let alone the indefinite wait for permanent residency faced by those assigned to category 5 under the priority processing system.

Chart 5: Permanent skilled migration entry vs temporary skill 457 visas 1999–11[33]

The government has also introduced a new form of temporary migration specifically designed to address spikes in demand for labour flowing from the resources boom, especially during the construction phase of major projects. This new mechanism is called an Enterprise Migration Agreement or EMA.

EMAs will be 'available to resources projects with capital expenditure of more than two billion dollars and a peak workforce of more than 1500 workers'.[34] EMAs can encompass not only skilled but also semi-skilled labour—that is, not just occupations with an Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO) skill level of 1, 2 or 3 (professions like engineering for example, or skilled trades), but also ANZSCO skill levels 3 and 4 (certificate level qualifications).

The government maintains that this will not displace workers or reduce domestic skills formation, since to be approved for an EMA projects will need to develop a comprehensive training plan:

- commit to training in occupations of known or anticipated shortage;

- commit to reducing reliance on overseas labour over time, with particular focus on semi-skilled labour;

- demonstrate that training strategies are commensurate with the size of the overseas workforce used on a project;

- demonstrate how training targets will be measured and monitored and enforced with contractors.

In addition, companies using EMAs are subject to the same requirement as employers using the 457 program, that they must either:

- contribute two per cent of payroll to a relevant industry training fund;

or

- spend one per cent of payroll on training their Australian employees.

The government also created a new special category of Regional Migration Agreements (RMAs): 'custom-designed' and 'geographically based', RMAs are designed to give regional employers 'streamlined access to temporary and permanent' migrant workers (both skilled and semi-skilled) 'where local labour cannot be sourced'.[35] As with 457 visas and Enterprise Migration Agreements, employers using RMAs will be required to commit to domestic training.

Will the conditions attached to these temporary migration programs really result in increased training and skills formation for the domestic population? Or do such schemes make it is easier for employers to hire offshore rather than to train locals—particularly locals who may come from disadvantaged backgrounds and who may require fairly intensive assistance? I do not pretend to know the answer to this question, but I think it is a question that we need to ask as the role of temporary migrants in our labour force continues to grow.

And I anticipate that there will be a continuing increase in long-term temporary migration as the politics of population influences policy.

The permanent migration intake was increased this year by almost 10 per cent; up from 168 700 to 185 000 places to the largest program (in absolute terms) in Australia's history.[36] But if the 'big Australia' debate at the last federal election is any indication of popular views, then unless they become far more adept at dealing with such issues as traffic congestion, environmental protection, urban amenity and housing affordability, future governments, whether Coalition or Labor, may find it difficult to increase the annual permanent migration intake, particularly at certain stages in the electoral cycle. On the other hand, there is concerted pressure from business to import skilled labour to feed the mining boom. Skills Australia forecasts a potential shortfall of 2.4 million workers over the next four years as 'an unprecedented pipeline of resource projects worth $132 billion is developed'.[37] The anticipated shortfall of skilled personnel rises to 5.2 million workers in 2025.[38]

I should point out that the Skills Australia numbers quoted here are at the top end of projections and assume an ambitious economic growth rate of close to four per cent per annum. The assumptions behind the report have not gone unchallenged. The link between major resource developments and the need for high levels of skilled migration has also been questioned, since mining is a capital—not a labour intensive—industry, and the biggest demands for workers will occur in the construction phase of mining projects, rather in long run operations.[39]

Nevertheless the squeeze between business pressure on the one hand and popular antagonism towards increased migration on the other, is likely in my view to produce a policy compromise in which temporary labour migration increases under the 457 program, EMAs, RMAs and perhaps other temporary migration schemes, which are not subject to any caps or quotas and which tend to happen below the media radar, particularly in regional and remote Australia. I think of this as a Clayton's immigration—the migrants you have, when you're not having migrants.

It is important to note that Australia's 457 program is qualitatively different from most other temporary migration schemes around the world. In Singapore, for example:

unskilled temporary migrant workers … do not have the right to marry, or cohabit, with a Singapore citizen or permanent resident. Female non-resident workers are also required to undergo mandatory pregnancy tests every six months, with the threat of immediate deportation in the case of a positive test result.[40]

Many labour migration schemes are restricted to single workers. Bangladeshi labourers or Sri Lankan maids working in the Gulf states generally travel alone and are often separated from family for years at a time. By contrast 457 visa holders can bring immediate family members with them to Australia and their spouses are also allowed to work. Workers on 457 visas are entitled to the same wages and conditions as their Australian counterparts and in recent years the federal government has enhanced these protections and the enforcement mechanisms that go with them.[41]

Nonetheless, foreign workers on the 457 scheme necessarily have diminished rights compared to Australian citizens or permanent residents. They cannot switch jobs as easily as their Australian counterparts because to be without work for 28 days means to be without a sponsor and will result in them being in breach of their visa conditions and liable for removal from Australia. Similarly, their ability to make use of such legal protections as unfair dismissal rights is severely curtailed.

Holders of 457 visas cannot be automatically compared with the guest workers or Gastarbeiter employed in the Federal Republic of Germany in the postwar period, since there is at least a potential path to permanent residency. Indeed considerable numbers of 457 visa holders have availed themselves of this option. Chart 6 shows that the number of 457 visa holders becoming permanent residents can be as high as half the number of new 457 visas issued any given year.

However a simple mathematical calculation makes clear that the path to permanent residency cannot be open to all. If it were the entire annual skilled migration program would be taken up with 457 visa holders with no room for applicants of any other type.

Given that the permanent migration intake is capped and the temporary migration intake is not, there is a risk here of an accumulating level of unmet demand—that is, of an emerging backlog of 457 visa holders who are seeking to become permanent residents but whose numbers overwhelm the annual permanent migration intake. In such a situation these 457 visa holders could well find themselves stuck indefinitely in a processing queue while they wait for their applications to be considered: exactly the situation that has arisen in relation to international student graduates in priority processing category 5.

Chart 6: 457 visas converting to PR 2001–11[42]

An alternative scenario is that increasing numbers of temporary migrant workers apply for a second or even a third 457 visa. This could see temporary skilled migrants working in Australia for periods of eight years or more. In such a case they would increasingly come to resemble the West German Gastarbeiter—paying tax, contributing to the society, but never receiving the benefits of permanent residency, let alone the voting rights that go with citizenship. Like student graduates stuck in the processing queue, they are in danger of becoming permanently temporary.

Is this the situation emerging in Australia?

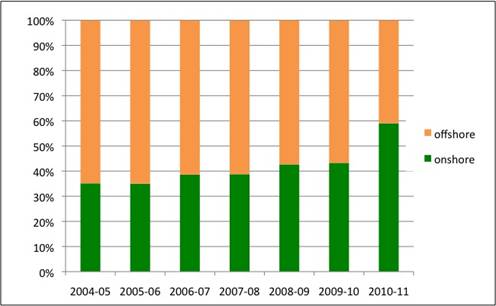

According to departmental figures, only 6390 temporary migrant workers have been here on 457 visas for more than four years, and just 1080 of them have been here for longer than six years.[43] So at this stage you could conclude that the potential 'guest worker' issue I'm flagging is not a significant problem—or at least not yet. However it is important to note that a significant proportion of 457 visas are issued on-shore (the proportion was 43.2 per cent of all applications granted in the 2010–11 program year)[44] (chart 7).

Chart 7: 457 visa grants off-shore/onshore[45]

This indicates not only that some workers are rolling over visas, but also that an increasing proportion of new 457 visas are granted to other visa holders already in Australia—like international students and working holiday makers.

So what appears in the statistics to be a four-year stay on a 457 visa, may in fact be a seven-year period of temporary residency in Australia, including three years of undergraduate study, before the 457 visa was granted. This points to two other substantial shifts in the nature of Australia's migration program in recent years that have gone almost unnoticed in the broader community: the rise of 'two-step' and 'employer sponsored' migration.

Two-step and sponsored migration

A significant proportion of temporary long-stay migrants do not leave Australia when their visas expire, but change their status. So, for example, a graduating student might move on to a 457 visa or a 457 visa holder might become a permanent resident. The proportion of 'new' permanent migrants who are actually 'old' temporary migrants has been steadily increasing. In the skilled migration program last year (2010–11), 59 per cent of permanent residence visas in were issued onshore (chart 8).

Chart 8: Share of permanent skilled migration visas issued onshore[46]

This trend to two-step migration is directly linked to a rise in employer sponsorship. In the past, most migrants applied for permanent residency in Australia independently—based on their qualifications, skills and experience. Now they are increasingly sponsored by their employers, or nominated by state and territory governments (chart 9).

Chart 9: Growth of sponsorship as a proportion of permanent skilled migration[47]

There are two components of employer sponsored permanent migration and both have been growing rapidly. The first is the Employer Nomination Scheme (ENS) (chart 10), which allows employers anywhere in Australia to sponsor skilled foreign workers for permanent residence in a broad range of occupations, provided they offer an annual salary of at least $49 330 (or $67 556 for certain information technology positions).[48]

Chart 10: Growth of the Employer Nomination Scheme (ENS)[49]

The second main component of employer sponsored migration is the Regional Sponsored Migration Scheme (RSMS) (chart 11), which allows employers 'in regional, remote and low population growth areas in Australia' to sponsor applications for permanent residence. The definition of regional is fairly generous—Perth has just been added to the list of eligible areas, so regional sponsorship now incorporates all of Australia except 'Sydney, Wollongong, Newcastle, Melbourne, Brisbane and the Gold Coast'.

The selection criteria are also more generous: any skilled occupation can be considered, as long as the nominated position offers an annual salary that 'meets any applicable Australia award or relevant legislation' and the visa applicant holds 'an appropriate Australian diploma-level or higher qualification'. In exceptional or compelling circumstances employers can nominate semi-skilled workers or workers without diploma level qualifications.[50]

Chart 11: Growth of the Regional Sponsored Migration Scheme (RSMS)[51]

Increasing the role of employer sponsorship in skilled migration is a deliberate government policy designed to shift Australia from a 'supply-driven' to a 'demand-driven' migration program. The changes were originally conceived under former Immigration Minister Senator Chris Evans, who said the shift was designed to ensure that Australia gets 'the skills that are actually in demand in the economy, not just the skills that applicants present with'.[52] Or putting it more bluntly, he said 'we don't want people coming in and adding to the unemployed queue'. Rather 'employers and state governments and the Commonwealth pick the people who we need'.[53]

There are many advantages to a sponsored 'two-step' or 'try-before-you-buy migration' process. It allows employers to test a visa applicant's 'work skills before sponsoring them for permanent residence' while temporary migrants 'have an opportunity to assess their employers and Australia' before making the decision to stay.[54] There is a potential downside however, as identified by industrial relations commissioner Barbara Deegan in her review of the 457 visa program. The employer's ability to give or withhold sponsorship is very powerful and makes temporary migrants who 'have aspirations towards permanent residency' particularly 'vulnerable to exploitation as a consequence of their temporary status'.[55] They may put up with 'substandard living conditions, illegal or unfair deductions from wages, and other similar forms of exploitation' in order not to jeopardise potential employer sponsorship. The situation is 'exacerbated where the visa holder is unable to meet the requirements for permanent residency via an independent application',[56] which will increasingly be the case, since the government has made it much harder to qualify for independent skilled migration.

It has done this by cutting back the list of skilled occupations under which a migrant can qualify independently for permanent residency, and by lifting the threshold for English language competency under the new skilled migration points test.[57] These measures will further accelerate the shift towards employer-sponsored migration as the dominant path to permanent residency.

New Zealanders

I come finally to the fourth group of long-term temporary migrants in Australia—New Zealanders, whose numbers have grown 24 per cent over the past five years. The growth is not as dramatic as with the other three groups I've discussed, but comes off a much higher base. So from around 450 000 (452 067) New Zealanders resident in Australia in 2005, we now have about 560 000 (559 308)—an increase of 110 000 Kiwis in five years.

Again it might seem strange to talk about New Zealanders as 'temporary migrants', since their entry into Australia is part of a long-standing reciprocal agreement between the two countries and they can stay for as long as they choose with no need to renew visas. And as Prime Minister Julia Gillard put it in her speech to the New Zealand Parliament in February 2011, 'New Zealand … is family',[58] a sentiment often repeated in the wake of the Christchurch earthquake a few weeks later.

Whether or not New Zealanders are truly 'family' might depend on your definition. After the Queensland floods and the devastation of Cyclone Yasi, many long-term New Zealand residents of Queensland felt themselves to be treated at best as poor cousins. Having lost homes, businesses and possessions, they discovered that they were not eligible for emergency government payments designed to help them keep their heads above water until they could re-establish their lives.[59]

Chart 12: New Zealanders in Australia (stock) 2005–10

After considerable lobbying on both sides of the Tasman, an ex-gratia payment was extended to them, but the experience has opened the eyes of many New Zealanders resident in Australia to what they see as structural discrimination resulting from legal changes over the past two decades. First was the introduction in 1994 of the Special Category Visa for New Zealanders, which changed the status of New Zealand citizens living in Australia, so that they were no longer automatically treated as de facto permanent residents. Then came legal changes resulting from the Family and Community Services Legislation Amendment (New Zealand Citizens) Act 2001.

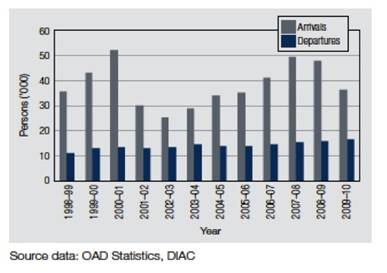

As its title suggests, the 2001 amendment was designed to limit the rights and entitlements of New Zealand citizens living in Australia. Specifically it prevents them accessing certain social security payments. This is understandable from an Australian government perspective since at the time there were about eight times as many New Zealanders living in Australia as Australians living in New Zealand.[60] The Australian Government was concerned that Australia's welfare system was a magnet drawing New Zealanders across the ditch. 'Australian officials expected New Zealand migrants to halve under the new restrictions',[61] which indeed they did, although numbers have increased again subsequently (chart 13).

Chart 13: New Zealand permanent and long-term arrivals and departures 1998–99 to 2009–10[62]

The knock-on effects of these changes for some individual New Zealanders have been profound. The National Welfare Rights Network gives the example of 'Toby', who came to Australia with his family in 2008 aged 14:

Two years later he left his family due to family violence and moved into a refuge. As he is here on a New Zealand passport he is not residentially qualified for Youth Allowance or Special Benefit.[63]

Toby survives with the support of a charity.

Depending on which state they live in the children of non-protected New Zealand citizens (that is those not already resident in Australia on 26 February 2001 when the amendment came into force) may not be entitled to disability services. The Brisbane Times recently reported that:

19-year-old cerebral palsy sufferer Hannah Campbell, who has lived in Australia for five years, has been refused financial assistance to attend day care—even though her father, Dave, has been working as a Toowoomba bus driver and paying Australian taxes.[64]

Assistance may even be denied to children who were born in Australia to New Zealand parents, since it is only after ten years continuous residence that a child is eligible to become an Australian citizen in his or her own right.

Unemployed, working-age children of New Zealand parents are unable to access benefits or the support and training opportunities that accompany Centrelink registration and children of 'non-protected' New Zealand citizens must pay upfront for university study and cannot access the HECS-HELP deferred payment scheme. Nor do they qualify for the 20 per cent discount on paying up-front fees.[65]

New Zealanders on Special Category Visas cannot apply for public sector jobs that require citizenship or permanent residency. This has led to situations where they have been denied employment by state agencies like the police or fire services, or where those agencies have had to seek special amendments to their own rules of employment in order to recruit New Zealanders resident in Australia. Non-protected New Zealand residents of WA, Victoria and Queensland are denied access to public housing. And of course New Zealanders resident in Australia are not eligible to vote in federal or state elections.

In short, many New Zealanders feel that Australian policy has made them into 'an underclass'.[66]

It might be objected that if New Zealanders are so concerned about their situation, then they should become permanent residents of Australia or take out citizenship. But this is no straightforward matter. New Zealanders can remain living and working in Australia as long as they like but the Special Category Visa does not confer residency rights, regardless of their length of stay. If New Zealanders wish to apply for permanent residency, then they will be assessed on the same criteria of health, age, skills and education as all other skilled migrants. This means for example that unprotected New Zealanders aged over 45, or those with limited qualifications, are highly unlikely to ever be eligible for permanent residency, let alone citizenship.

On one level it might seem fair that New Zealanders are not given any special advantages over other nationalities when seeking Australian residency or citizenship. But compare this to the reverse situation: Australian citizens living in New Zealand become eligible to apply for citizenship, tertiary student allowances and student loans, as well as all social security benefits after a qualifying period of two years residency.

The Special Category Visa that confers on New Zealanders the option to live and work indefinitely in Australia runs the risk of creating another group of long-term residents who are in effect, permanently temporary and whose rights and entitlements are curtailed as a result.

Conclusion

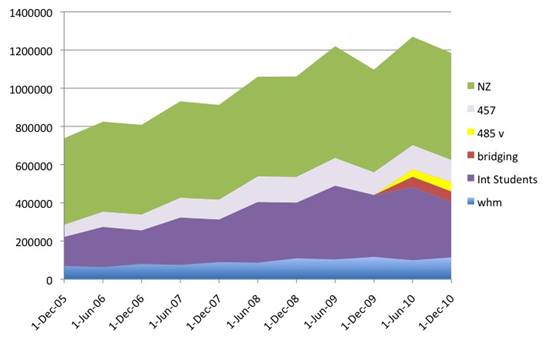

In this presentation I have identified some fundamental changes to Australia's migration program, in particular the rise of temporary migration. Long-term temporary residents in Australia fall into four main categories—working holiday makers, international students, temporary migrant workers and New Zealanders—and together they number more than one million people or about five per cent of the Australian population. While the number of these temporary residents present in Australia at any one time peaked a couple of years ago, the total is still more than 60 per cent higher today than in 2005 (chart 14).

Chart 14: Temporary and bridging visas (stock) 2005–10

It is my contention that numbers will grow in the future. This is not predetermined: young working holiday makers may decide to stay in Ireland or South Korea rather than venture to the Great South Land; New Zealanders may decide their economic prospects are better at home; Australian businesses may lose their appetite for importing temporary foreign workers. But I doubt it. Until this week, it was perhaps more likely that enrolments of international students would continue to fall, but the federal government's response to the Knight Review of the Student Visa Program has changed that. The government is now offering temporary work visas to any international students who complete a degree at an Australian university: a two year visa for a bachelor degree, a three year work visa for a masters degree and a four year work visa for a PhD.[67] Combined with other changes to international student visas this is likely to make study in Australia more attractive and increase student numbers resulting in a further increase in the stock of long-term temporary migrant workers present in Australia at any one time.

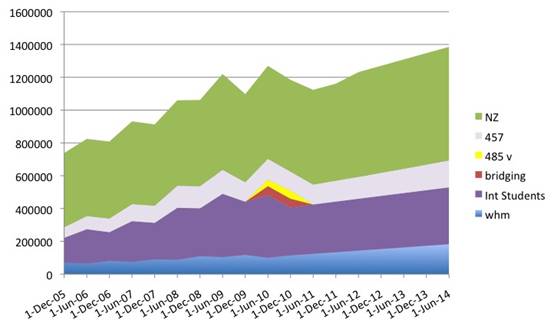

Chart 15: Projected stock of long-term temporary residents 2005–14[68]

Projections by the Department of Immigration and Citizenship—made prior to the recent changes to student visas—already predicted steady growth in the number of long-term temporary residents out to 2014 (chart 15). Growth was not anticipated to be as rapid as in past, but numbers would still outstrip overall population growth, so that by 2014 the total number of temporary residents in Australia will be approaching 1.4 million people.

The question is does this matter? Does it matter if we have a growing number of temporary migrants living amongst us? After all, we live today in a far more educated, globalised and mobile world. Temporary movement across borders to take up a job, pursue a career, gain experience or study is part of contemporary life. Australians are also going overseas in record numbers to live, study and work for long periods of time.

There is also a great deal of churn in this population of long-term temporary residents. The Canadian backpacker who is here in June 2007 is not the same Canadian backpacker who will be here in June 2014. The turnover of international students and temporary migrant workers is slower, but generally they too leave Australia and return home when their visas expire. New Zealanders may stay longer but they can come and go as they please. We have made no promises to these groups, and we owe them no legal obligations in relation to permanent residency. The terms of the deal are clear: come to Australia to study, work, live for a period of time and while there may be the potential of permanent residency down the track, that is not an automatic right or expectation.

Perhaps I am making a mountain out of a molehill. But a number of trends apparent from my survey of temporary migration give pause for thought.

The first is the tendency for what might be called visa policy creep: that is, a visa initially created for one quite specific purpose, ends up being expanded to achieve a different end. This is most evident in the Working Holiday visa, which has been used to address labour market issues in regional areas and in the 457 visa, which is no longer a stop-gap measure to provide a breathing space for our training system but a mechanism to respond rapidly to changing business demands for skilled labour (and which is being supplemented with new forms of temporary labour migration like Enterprise Migration Agreements).

The second tendency is for numbers to increase, quite rapidly, once these uncapped temporary visa categories are created. This is not surprising when there are strong incentives to take advantage of the opportunities these visas offer: to employers and foreign workers, to tertiary institutions and overseas students.

The third tendency is for government to respond to the increase in numbers by adjusting policy in ways that limit the rights and entitlements of temporary migrants when they become administratively or politically inconvenient. The legislative change affecting New Zealanders resident in Australia is one example; the introduction of priority processing to indefinitely delay valid permanent residency applications by international student graduates is another. It could be argued in relation to 457 visa holders that the trend has gone the other way: since the election of the Rudd Government the 457 scheme has been subjected to more stringent rules, inspections and safeguards. These changes were made in response to recommendations contained in a report into the integrity of the 457 scheme commissioned by the federal government.[69] However, other recommendations, which would have enhanced the rights of 457 visa holders and expanded the opportunities for permanent residency, were not taken up.[70]

My biggest concern is that the growth of temporary migration, coupled with restrictions in the growth of the annual permanent migration intake, will have the unintended but damaging consequence of creating a growing group of long-term residents of Australia who are in a kind of limbo, like that experienced already by the international student graduates stuck in priority processing group 5. This could happen, for example, if the number of 457 visa holders seeking permanent residency continues to increase and outstrips the annual migration intake, creating another major backlog in the system. We could see growing numbers of international student graduates, 457 visa holders, New Zealanders and others forming attachments to Australian citizens and then seeking spousal visas—particularly if there is a long wait for skilled migration—and this would create a backlog of applications in the spousal and family migration program as well.

Still, it might be argued that the numbers are relatively small and so that even if there are some disgruntled individuals, some losers in the 21st century Australian migration system, the issue is not that serious. Leaving aside the fact that such an argument shows scant regard for the rights of the individual, I would suggest that the numbers involved are not trivial.

It is interesting to make a quick comparison to West Germany in the mid-1970s. The recruitment of workers under West Germany's Gastarbeiter program was formally ended in 1973—after it became clear to federal authorities that 'foreign labour was beginning to lose its mobility, and social costs (for housing, education and healthcare) could no longer be avoided'.[71] At this time, the minority population in the Federal Republic of Germany—that is foreign residents, not naturalised—was around four million—or about 6.6 per cent of the population.[72] It is not vastly different to five per cent of Australia's population today who are temporary migrants. Of course most temporary migrants do not want to stay in Australia permanently; but most guest workers went home too, only a minority remained in West Germany.

I have argued that the number of temporary residents in Australia will continue to increase. True, it will not be the same individuals who make up that group—there will be a high degree of turn-over as some migrants leave and others arrive. Nevertheless, like the Gastarbeiter in West Germany, this changing group will still represent a continuous cohort of people, a permanent social group with varied but particular interests, who have no formal representation in our political system. For the purposes of government administration they are regarded as non-Australians. The popular view of this cohort is likely to replicate their formal status—as not belonging to this society and not accruing rights within it—let alone amassing affections and attachments. There is a risk that temporary migrants will be regarded as a useful economic input that can be discarded when no longer required. As 'guests', offered an opportunity to 'work', they should do so without complaint, or risk being perceived as ungrateful and troublesome when they refuse to act like machines and exhibit instead the wants and desires of human beings.

The problem is that human beings cannot be reduced to units of production in the mining industry or export dollars for the education sector.

As the Swiss playwright, Max Frisch said so memorably about guest workers in Europe in the 1960s, 'Man hat Arbeitskräfte gerufen, und es kamen Menschen'—'We called for labour power and people came'.[73] The longer temporary residents stay in Australia, the more likely they are to build up a bundle of connections—emotional, psychological, cultural and financial—connections that bind them here, and which bring with them expectations of some kind of reciprocity on behalf of the Australian state. This is the contradiction inherent in temporary migration identified by Stephen Castles and Mark Miller: schemes are devised on the basis that the sojourn will limited and that 'the legal distinction between the status of citizen and of foreigner' will provide a clear criterion for conferring them with different levels of political and social rights. However with the passage of time come 'inexorable pressures for settlement and community formation'.[74]

This is not to say that every foreign citizen who comes to Australia for an extended stay should have the right to remain permanently. Nor am I suggesting that we should end all temporary migration. I am just flagging the tensions that arise when a government, in pursuit of the national interest, opens its borders to migrants without offering them the benefits of citizenship.

Over time, as temporary residents work, pay taxes and contribute to society in other ways, we start to move from the realm of technical legal rights, to the realm of ethical and moral rights. At what point should a person have the right to become an Australian? Our law makers have answered this question in one limited way: a child born in Australia to foreign parents, who lives in Australia continuously for ten years, acquires the right to claim Australian citizenship. Why ten years and not five or fifteen? Why does the same right not flow to a child who is born overseas but arrives in Australia at the age of one month? Why should adults not acquire similar rights after long periods of residence?

I do not know the answers to these questions but I think they are questions that we need to discuss.

The changes to Australia's skilled migration program—the increase in temporary and employer-sponsored migration—are designed to be 'highly responsive to emerging skill needs' and to 'benefit productivity growth, participation and economic growth in general'.[75] In statistical terms, they appear to be working: employer sponsored and temporary 457 skilled migrants earn wages well above the Australian average and are far more likely to be in full-time skilled work. However I become uneasy when I hear phrases like this: it is crucial to harness 'the benefits and value that Australia derives from each program place'.[76] We are in danger of focussing on the 'Arbeitskräfte'—the labour power—and losing sight of the 'Mensch'—the human being.

In conclusion I'd like to shares some quotes that I think could guide us when we consider the growth of temporary migration and our policy responses to it. A true multiculturalism will be one that invites:

every individual member of society to be everything they can be … supporting each new arrival in overcoming whatever obstacles they face as they adjust to a new country and society and allowing them to flourish as individuals.[77]

This is important because 'if people do not feel part of society, this can lead to alienation and, ultimately, social disunity'.

Those are the words of the Minister for Immigration and Citizenship, Chris Bowen, from his speech on multiculturalism that I quoted at the beginning of this paper.

Question — My question relates to labour market testing that employers may or may not have to do in order to bring in temporary migrants. We often hear that there is a skills requirement from the mining industry. The mining industry employs less than two per cent of the workforce and their training of apprentices is less than half the industry average. I'm wondering what tests do employers have to pass in order to bring in outsiders?

Peter Mares — There's no labour market testing. So there is no testing of the local labour market for either the enterprise migration scheme or the 457 scheme, but there are a range of other requirements on employers which go to probity and record and things like that. One thing I would say about the 457 scheme is it was subject to a great many abuses and the Rudd Government, after the review by Barbara Deegan, did introduce much tighter monitoring and higher penalties and so on and I haven't looked at that question of abuses in detail lately, but the abuses do seem—this is very anecdotal from my reading of it—to have been reduced. So I think the scheme is being operated more tightly, but one thing the trade unions would like to see is more labour market testing in particular areas as to whether it is appropriate. So you do have this division between regional and non-regional but, as I said, in most cases 'regional' is almost anywhere in Australia apart from Melbourne, Sydney, the Gold Coast, Brisbane, Canberra, Newcastle and Wollongong. So, for example, Perth was recently added to the regional category because employers in Perth were complaining about the lack of labour because of the mining industries sucking labour out of Perth.

Question — I see a problem with the ethical and moral issues in relation to the various types of immigration programs, because what we are using in effect is other countries' taxpayers to actually fund the progress in Australia. When we look at 457 visas and some of the other visas as well, there is a demand from industry to import trained people and there is no investment on the part of the mining organisations for them to actually invest in training and education themselves. With mining in particular, they go through boom and bust so we've got a situation where we have got a lot of workers being imported on their whim by the government and subsequently being dropped when the industry busts.

Peter Mares — That is exactly why the 457 visa is seen as a good thing, because it is flexible. When there is a sharp spike in demand for labours as there is with the resources boom, that can be met by bringing in skilled migrant labour on a 457 visa and if that drops off, it can be reduced again. That's the theory. In fact, the 457 visa numbers did drop significantly during the global financial crisis. Demand for them here in Australia went down significantly, so that would be the economic justification.

As to the ethical issues around importing skills paid for by other countries' taxpayers, I'm sure the government could see that from a national interest perspective it is a very sensible idea. It's what's often referred to as brain drain and there is very interesting literature around this question. It's not a straightforward question of us just pinching all the doctors and nurses from the Philippines. It's more complicated than that. For one thing, who are we to tell a doctor or a nurse in Zimbabwe that they should work on next to no pay when they have an opportunity to improve their personal and family situation by working for much better pay in Australia? That's another side of the ethical dilemma.

Another part of it is that the demand for skilled labour from a country like the Philippines results in a huge boost in training of exactly that type of skilled labour in that country, so that to meet that market you get a boost. I'm not saying this is unproblematic at all, there are lots of ethical issues involved, particularly when you start seeing Australia attracting nurses from small Pacific Island states, for example, where the replacement for those nurses will be much harder to achieve and there are various ethical suggestions around for dealing with this. The health sector is one of the biggest users of 457 visas, so it is state and territory governments, not just the mining industry that uses these visas. There are suggestions that, for example, there should be investment back into the source countries' education training system by Australia or by employers or that the skilled workers we bring in be under some type of program where they go back to work in their own country. There are various quite innovative ways in which we can approach the ethical issues you have raised.

Question — My question relates to the human circumstances of people on 457 visas. You mentioned that people seeking extensions of 457 visas may be beholden to employers and subject to less than satisfactory conditions and circumstances. Is there any public scrutiny or investigation of exploitation of people on these sorts of visas?

Peter Mares — Well as I said in response to the earlier question, the Rudd Government tightened up the monitoring quite considerably and put more resources into monitoring and the Fair Work Ombudsman and trade unions have been quite active in this area. I think the area in which the biggest problem arises is not so much renewing the 457 visa, but trying to move from 457 to permanency in terms of the power differential that creates between employer and worker. Now this isn't to denigrate all employers of 457 visas and most often the employer is keen to keep the worker because they have already worked for the business for some time, they have built up skills and knowledge, all that sort of thing. But we did see the biggest abuses were in areas of trades. For example, chefs employed by restaurants, including here in Canberra. There was one notorious example of a 457 visa holder who complained about his situation to the immigration department and his boss then tried to kidnap him and take him to the airport. Luckily, their car was stopped for speeding on the way to Sydney and the Filipino chef involved managed to make his case known to the police officer who had pulled them over. So abuses have existed and I haven't done any detailed research recently but I think the situation is better than it was before with the various new mechanisms that were bought in.

Question — Have you had any opportunity to reflect on the situation here and in the United States, for example, which is also a big market for temporary migrants and whether there are any comparisons to be made in that regard?

Peter Mares — I think the situation is very different in the sense that while we hear a lot about illegal arrivals in relation to boats, Australia in relative terms does not have a problem with undocumented migrants or what in popular parlance would be called 'illegals'. That is, people living in Australia without authorisation. There are around sixty thousand overstayers—that is, people who have come to Australia on a legitimate visa like a tourist visa or a student visa and then haven't left when their visa expired. Fifty to sixty thousand is a tiny number in terms of overall population compared to the US where you have ten million undocumented migrants. The much more deregulated labour force in the US makes it much more possible to survive, albeit in very tenuous circumstances, as an undocumented migrant in the US. Our immigration department knows everyone who enters this country, because we have a universal visa system. They know when people haven't left. There are no land borders. We have quite a sophisticated mechanism for tracking down overstayers and finding them. In that sense it is quite different, and the US has a whole lot of other temporary migrant programs, and some are skilled and so on. The big difference is that we don't have that undocumented labour force who are much more vulnerable. International students do get ripped off in some jobs in Australia, but they do have recourse, we do have laws, we do have a more regulated labour market, there are places they can go to, the Fair Work Ombudsman and so on. Much more so than if you were illegal where you can't bring yourself to the attention to authorities because you undermine your own ability to stay in the country.

Question — It's interesting that you mentioned the Philippines, because the Philippines has nine million Filipinos overseas and about four million of them are temporary workers and so the duty of the government is to protect migrant workers and not to exploit them as labourers. I'd like to ask what are some of the bilateral agreements between the Australian Government on a government to government arrangement where the processing of migrants is protected not just by the receiving country but also but the source country?

Peter Mares — I would say that the Philippines has led the world in relation to attempting to extend protection to its own workers. The Philippines has been a major exporter of labour, including quite a lot of skilled labour, for quite some time. And so the Philippines is ahead of many other countries in terms of thinking about these issues. Australia doesn't have any bilateral agreements of that nature to my knowledge, the exception being the very small Pacific Seasonal Worker Pilot Scheme. I distinguish it from long-term temporary migration because it is a circular program. I did quite a lot of research on it a few years ago. That's an idea in which you would have people come from Pacific Islands and there is a memorandum of understanding between Australia and that country and they would work for three or four months in a seasonal labour job like fruit picking. This is partly a development initiative because as we know there are high levels of unemployment and a youth bulge in the Pacific and this is a way of trying to extend that back. In my view it is better from an Australian perspective for Pacific Islanders to be taking those sorts of jobs than, say, Canadian backpackers. That program is very specific, small scale and in its pilot stages but I understand it is beginning to pick up speed. It is very successful in New Zealand where they have a similar program.

So apart from that there is the United Nations Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families and a whole lot of countries have ratified that but they are all migrant labour sending countries, not migrant labour receiving countries. The convention is meaningless until recipient countries like in Europe, America and Australia ratify that convention.

* This paper was presented as a lecture in the Senate Occasional Lecture Series at Parliament House, Canberra, on 23 September 2011.

[1] Australian Bureau of Statistics, '6 million migrants call Australia home', media release 75/2011, 16 June 2011, online at http://www.abs.gov.au/ausstats/abs@.nsf/Products/A6B6AC80B29DE8F3CA2578B000119758?opendocument, accessed 13 September 2011.

[2] In 2011–12, confirming a long-term trend, the number of permanent skilled places in the migration program was increased by 12 000, while the number of family places rose by only 4050 'reinforcing the … focus on skills'. Kruno Kukoc (First Assistant Secretary, Migration and Visa Policy Division Department of Immigration and Citizenship), 'Australia's migration programs: contributing to Australia's growth and prosperity', presentation to the Committee for the Economic Development of Australia (CEDA) discussion forum, 14 September 2011, online at http://www.immi.gov.au/about/speeches-pres/_pdf/2011/2011-09-14-ceda-speech.pdf.

[3] Chris Bowen, Minister for Immigration and Citizenship, 'The genius of Australian multiculturalism', address to the Sydney Institute, 17 February 2011, online at http://www.minister. immi.gov.au/ media/cb/2011/cb159251.htm, accessed 9 August 2011.

[8] The total number of international students, New Zealanders, working holiday makers and 457 visa holders present in Australia on 31 December 2010 was 1 080 677. Compilation of data supplied in tables 4.1, 4.5, 4.6 and 4.7 in Immigration Update, July to December 2010, Department of Immigration and Citizenship, Canberra, 2011, online at http://www.immi.gov.au/media/ publications/statistics/immigration-update/update-dec10.pdf.

[9] Mark Cully, 'Migrant labour supply: its dimensions and character', paper presented to the Australian Labour Market Research Workshop, University of Sydney, 15–16 February 2010. The figure varies between 4.2 per cent and 6.4 per cent of the overall labour force and between 17.9 per cent and 22.3 per cent of the labour force in the 20–24 year old age bracket, according to the assumptions made about how active these temporary long stay migrants are in the workforce.

[10] Department of Immigration and Citizenship, 'Fact sheet 49—Working Holiday Program', online at http://www.immi.gov.au/media/fact-sheets/49whm.htm, accessed 9 August 2011. The Working Holiday visa is available to passport holders from Belgium, Canada, the Republic of Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hong Kong SAR, the Republic of Ireland, Italy, Japan, the Republic of Korea, Malta, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Taiwan and the United Kingdom.

[11] Bangladesh, Chile, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, Turkey and the United States. Department of Immigration and Citizenship, 'Fact sheet 49a—Work and Holiday Program', online at http://www.immi.gov.au/media/fact-sheets/49awhp.htm, accessed 9 August 2011.

[12] Department of Immigration and Citizenship, 'Fact sheet 49—Working Holiday Program', op. cit.

[13] Unless otherwise stated all data used in these charts are stock figures—that is the number of people in these visa categories actually present in Australia on the dates in question—rather than the number of visas issued in a particular year. The statistics are taken from the regular Immigration Update produced by the Department of Immigration and Citizenship and available online at http://www.immi.gov.au/media/publications/statistics/.

[14] Department of Immigration and Citizenship, 'Working Holiday—specified work', online at http://www.immi.gov.au/visitors/working-holiday/417/specified-work.htm#a, accessed 9 August 2011.

[15] Department of Immigration and Citizenship, 'Working Holiday—regional Australia postcode list', online at http://www.immi.gov.au/visitors/working-holiday/417/postcodes.htm, accessed 9 August 2011.

[16] Cully, op. cit.

[20] Australian Bureau of Statistics, Labour Force (catalogue number 6202.0), July 2011, tables 13 and 17.

[21] Bob Birrell, Ernest Healy, Katharine Betts and Fred T. Smith, 'Immigration and the resources boom mark 2', Monash University Centre for Population and Urban Research, research report, July 2011, p. 11, online at http://arts.monash.edu.au/cpur/publications/documents/immigration-policy-13-july-2011.pdf, accessed 18 August 2011.

[22] Department of Immigration and Citizenship, '2010–11 migration program planning: consultations with key state and territory representatives December 2009 to July 2010', presentation, slide 14 of 22.

[23]Department of Immigration and Citizenship, 'Fact sheet 24a—priority processing for skilled migration visas', online at http://www.immi.gov.au/media/fact-sheets/24apriority_skilled.htm, accessed 9 August 2011.

[24] Senator Chris Evans, Minister for Immigration and Citizenship, 'Changes to Australia's skilled migration program', address presented at the Australian National University, 8 February 2010, online at http://www.minister.immi.gov.au/media/speeches/2010/ce100208.htm, accessed 16 September 2011.

[25] Senator Chris Evans, doorstop interview, Canberra, 8 Feb 2010, online at http://www.minister.immi.gov.au/media/speeches/2010/ce100208a.htm, accessed 16 September 2011.

[26] Figures supplied by the Department of Immigration and Citizenship via email in response to a question by the author, 7 July 2011.

[27] Department of Immigration and Citizenship, 'Information regarding your application for a Subclass 885 Skilled—Independent Visa', 13 July 2011. Copy supplied to the author by an informant.

[28] See for example Peter Mares, 'A blockage in the skilled migration pipeline', Inside Story, 3 November 2009, online at http://inside.org.au/a-blockage-in-the-skilled-migration-pipeline/.

[29] Statistics supplied by Department of Immigration and Citizenship officers by email, 12 August 2011, in response to a question by the author.

[31]Department of Immigration and Citizenship, 'Skilled—Graduate (Temporary) Visa (Subclass 485)', online at http://www.immi.gov.au/skilled/general-skilled-migration/485/, accessed 19 August 2011.

[32] Department of Immigration and Citizenship, 'Employer Sponsored Workers—additional funding for 457 visa processing', online at http://www.immi.gov.au/skilled/457-additional-funding.htm, accessed 9 August 2011 and Chris Bowen, Minister for Immigration and Citizenship, 'Budget 2011–12: new temporary migration agreements to further address skills demand', media release, 10 May 2011, online at http://www.minister.immi.gov.au/media/cb/2011/cb165283.htm, accessed 26 September 2011.

[33] Data used in this chart was assembled from two sources accessed on the Department of Immigration and Citizenship website: annual reports of the department (http://www.immi.gov.au/ about/reports/annual/) and the 'Subclass 457—Business (Long Stay) Visa statistics', (http://www.immi.gov.au/media/statistics/statistical-info/temp-entrants/subclass-457.htm).

[34] Department of Immigration and Citizenship, 'Fact sheet 48a—Enterprise Migration Agreements', online at http://www.immi.gov.au/media/fact-sheets/48a-enterprise.htm, accessed 22 August 2011.

[35] Department of Immigration and Citizenship, 'Regional Migration Agreements', online at http://www.immi.gov.au/skilled/regional-migration-agreements.htm, accessed 16 September 2011.

[36] Department of Immigration and Citizenship, '2011–12 migration program', online at http://www.immi.gov.au/skilled/_pdf/migplan11-12.pdf.

[37] Louise Dodson, 'It's a 2.4 million problem', Weekend Australian Financial Review, 14–15 May 2011, p. 27.

[39] Birrell, Healy, Betts and Smith, op. cit.

[40] M. Ruhs and H. Chang, 'The ethics of Labor immigration policy', International Organization, no. 58, winter, 2004, p. 72.

[41] Peter Mares, 'The permanent shift to temporary migration', Inside Story, 17 June 2009, online at http://inside.org.au/the-permanent-shift-to-temporary-migration, accessed 9 August 2011.

[42] Data used in this chart was assembled from two sources accessed on the Department of Immigration and Citizenship website: annual reports of the department (http://www.immi.gov.au/ about/reports/annual/) and the Subclass 457 Business (Long Stay) Visa Statistics (http://www.immi.gov.au/media/statistics/statistical-info/temp-entrants/subclass-457.htm).

[43] Data provided by email, 22 August 2011, in response to an inquiry from the author.

[44] Department of Immigration and Citizenship, 'Subclass 457 state/territory summary report 2010–11 to 30 June 2011', online at http://www.immi.gov.au/media/statistics/pdf/457-stats-state-territory-jun11.pdf, accessed 9 August 2011.