75 Proposal for debate

-

A senator may:

-

propose that a matter of public importance be submitted to the Senate for discussion; or

-

move a motion, without notice – That in the opinion of the Senate the following is a matter of urgency: [here to be specified the matter of urgency].

-

The senator proposing the matter of public importance or the motion to debate the matter of urgency shall hand to the President, not later than 12.30 pm on the day to which the proposal relates, a written statement of the proposed matter of public importance or urgency.

-

If the proposal is in order, the President shall read it to the Senate at the time provided.

-

In order to proceed the proposal must be supported by 4 senators, not including the proposer, rising in their places.

-

If more than one proposed matter of public importance or urgency is presented for the same day, priority shall be given to that which is first handed to the President. If 2 or more proposals are presented simultaneously, the proposal to be reported shall be determined by lot. No other proposal shall be read to the Senate that day.

-

A motion to debate a matter of urgency may not be amended.

-

Debate on a matter of public importance or urgency motion shall not exceed 60 minutes, or, if no motions are moved after question time to take note of answers, 90 minutes, and a senator shall not speak to such a matter or motion for more than 10 minutes. At the expiration of the time for a debate the question on a matter of urgency shall be put.

-

At any time during the discussion of a matter of public importance, a motion may be made by any senator, but not so as to interrupt another senator speaking, that the business of the day be called on. No amendment, adjournment or debate shall be allowed on such motion, which shall be put immediately by the President, and if the motion is agreed to, the business of the day shall be proceeded with immediately.

Amendment history

Adopted: 19 August 1903 as SO 59A (renumbered as SO 60 in the first printed edition)

Amended:

- 1 September 1937, J.44 (to take effect 1 October 1937) (removal of superfluous limitation on subject of debate)

- 2 December 1965, J.427 (to take effect 1 January 1966) (written notice to be given to President before commencement of sittings)

- 20 August 1975, J.860 (new form of question adopted after 6 month trial by sessional order)

- [8 March 1978, J.60 (sessional order adopted replacing procedure for urgency motion with matter of public importance for discussion)]

- [23 August 1979, J.883–84; re-adopted 26 November 1980, J.23 (sessional order adopted combining urgency motion and matter of public importance as alternatives)]

- 26 November 1981, J.716–17 (sessional order combining urgency motion and matter of public importance as alternatives adopted as a permanent standing order in place of old SO 64)

- 13 February 1997, J.1447 (to take effect 24 February 1997) (changes to paragraphs (3) and (7) consequent on the incorporation of 1994 reforms to the routine of business, as modified by subsequent sessional orders)

1989 revision: Old SO 64 renumbered as SO 75; provision made for deciding between two or more simultaneously presented proposals and for the question to be put when time expires; language simplified and streamlined

Commentary

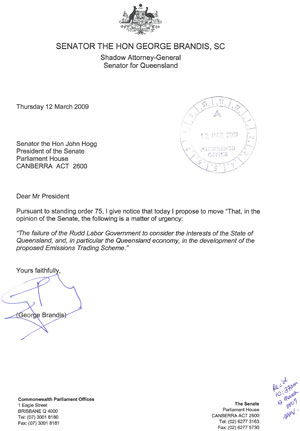

An example of an urgency motion

In its original form, SO 75 followed the ancient parliamentary practice of a motion for the adjournment of the Senate to an unusual time in order to discuss a “definite matter of urgent public importance”, which the proposer then handed to the President in writing. It was a procedural device to provide an opportunity for debating urgent matters, recognising the right of a minority to be heard before the business of the government began.[1] It did not involve a vote on the substantive matter and the motion was usually withdrawn, by leave, when contributions had concluded although, occasionally, a vote was taken.[2] The Senate would then proceed to its ordinary business until a minister, at the appropriate time, moved the motion for the genuine adjournment of the Senate. Even before the Senate adopted permanent standing orders, such motions were common, based on its temporary standing orders.[3]

Unlike in the temporary standing orders, both types of adjournment motion were dealt with as one standing order in the draft proposed by the Standing Orders Committee, which closely followed Blackmore’s draft (as modified by Senator O’Connor (Prot, NSW)) and the equivalent standing orders of the Victorian Houses. At four senators, the level of support required for such a motion to be entertained was lower than in any of the sources, but this number ensured that matters of great importance could be raised by the representatives of an individual state if necessary.[4] The draft included a time limit of three hours.

Although agreed to initially on 10 June 1903, the standing order was reconsidered on 13 August and, at the initiative of Senator Pearce (ALP, WA), divided into two separate standing orders to deal with the two completely separate procedures.[5] The standing order as adopted, stripped of its melodramatic expression, now read as follows:

(1) A motion without notice, that the Senate at its rising adjourn to any day or hour other than that fixed for the next ordinary meeting of the Senate for the purpose of debating some matter of urgency, can only be made after Petitions have been presented and Notices of Questions and Motions given, and before the business of the day is proceeded with, and such Motion can be made notwithstanding there be on the paper a Motion for adjournment to a time other than that of the next ordinary meeting. The Senator so moving must make in writing, and hand in to the President, a statement of the matter of urgency. Such motion must be supported by four Senators rising in their places as indicating their approval thereof. Only the matter in respect of which such Motion is made can be debated. Not more than one such Motion can be made during a sitting of the Senate.

(2) In speaking to such Motion, the mover and the Minister first speaking shall not exceed thirty minutes each, and any other Senator or the mover in reply shall not exceed fifteen minutes, and every Senator shall confine himself to the one subject in respect to which the Motion has been made. Provided that the whole discussion of the subject shall not exceed three hours.

In the 1937 review, a small change was made to paragraph (1) to remove the second last sentence (see above). The proposal from the Standing Orders Committee came virtually without explanation and was adopted without debate. The only clues are in the report’s brief introduction with its reference to “the desirability of including certain amendments to provide for what is the present practice of the Senate, and in other cases to clarify the verbiage”.[6] As the amendment was not an inclusion but an omission, its purpose was probably in relation to clarifying the verbiage. In view of the general rules about relevance, expressed in numerous rulings by Presidents Baker, Gould, Givens and Newlands in respect of this very standing order, the sentence was redundant and was probably removed accordingly. An argument that it had probably been included originally to distinguish this debate from the adjournment debate proper where matters not relevant to the question could be debated has no support. Authorisation for debate of matters not relevant to the adjournment question did not come until 7 October 1903, after the standing orders had been agreed to.[7] The phrase was in two of the sources (Blackmore’s draft and the standing orders of the Victorian Legislative Council), as well as in South Australian Legislative Assembly SO 48. It may simply have been adopted in 1903 without sufficient critical thought.

The 1966 amendment added a requirement for the matter of urgency to be handed in writing to the President “before the time fixed for the meeting of the Senate”. This was not a new requirement but a formalisation of the practice that had been in place for many years, based on rulings of Presidents Givens and Hayes, although, as Edwards notes in the 1938 MS, the rulings were disregarded when it suited the convenience of the Senate. He gives an instance on 1 June 1938 “when the Leader of the Opposition desired to ventilate a certain matter on a question of privilege, and the President (Senator Lynch) suggested that it should be done on a motion for adjournment. In this case the statement of the matter of urgency was prepared and handed to the President some time after the Senate had met”.

By the early 1970s, ideas were emerging about how the procedure might be usefully changed but there was no consensus on how far the changes should go. The Standing Orders Committee proposed some modest changes in its August 1971 report (PP No. 111 /1971) without addressing the fundamental absurdity of the mechanism. Although the proposals were extensively debated on three separate occasions, no solution emerged to difficult questions about the actual mechanism, whether there should be a vote on the subject matter, the amount of notice required and time limits for the debate. The matter was referred back to the committee for further consideration.[8] Meanwhile, a resolution of the Senate of 18 May 1972 expressed support in principle for a two hour time limit (down from three). A further report from the Standing Orders Committee in October 1972 (PP No. 178/1972) made similar recommendations but was never dealt with. In 1975, the Third Report of the Standing Orders Committee (PP No. 277/1974) concluded that the present procedure was “antiquated and should be discarded.” This report was also extensively debated. The result was a sessional order agreed to on 11 February 1975 adopting a new form of urgency motion. Rather than a motion to adjourn to an unusual time, the motion would take the form:

That in the opinion of the Senate, the following is a matter of urgency: [here specify the matter of urgency]

A proposal would be required to be lodged with the President at least 90 minutes before the commencement of the sittings and the time limit would remain at three hours. The new sessional order came into effect on 18 February 1975 and was adopted as an amendment to standing orders on 20 August 1975 after a six month trial.[9]

An idea that had been canvassed in the first of the debates on the August 1971 Standing Orders Committee report, to avoid the vexed issue of voting, was the matter of public importance which could be submitted for discussion without there being a question before the chair.[10] In its First Report for 59th Session (PP No. 27/1978), the Standing Orders Committee recommended that the procedure for urgency motions be replaced by a procedure for discussion of matters of public importance, closely modelled on House procedures. The proposed new standing order, to be tried as a “Sessional Order for 1978”, was considerably modified before being adopted, with an emphasis on protecting the rights of minority groups and independent senators. The time limit was cut from three hours to two; the requirement for there to be four signatures on the letter in addition to the proposer’s was replaced with the previous practice of four senators indicating support by standing along with the proposer on announcement of the proposal; and the discretion of the President to determine the most urgent and important proposal in the event that more than one was submitted was replaced with the principle of “first in, best dressed”.[11]

On reviewing the sessional order the following year, the Standing Orders Committee came back with a proposed new standing order (again, to operate first as a sessional order for a trial period) that combined both procedures, giving senators the option to move an urgency motion or propose a matter of public importance for discussion. The proposal was agreed to after little more than tokenistic cavilling at the reduction of time available from three to two hours (already in place) by that veteran champion of the rights of senators, Senator Cavanagh (ALP, SA).[12] By the end of 1981, when the Standing Orders Committee next looked at the issue, the new combined procedures had been in operation for more than two years and the recommendation that they operate on a permanent basis was agreed to without debate.[13]

Following a change of government in 1983, some adjustments were made from time to time to the days of meeting and routine of business. From April 1983, MPIs or matters of urgency could be proposed on two out of three sitting days each week.[14] From February 1984, an eight day sitting fortnight was adopted with an opportunity on every sitting day to propose an MPI or matter of urgency. Furthermore, senators now had until 12.30 p.m. each day to lodge their proposals.[15] A similar arrangement operated from February 1985 but with a timeframe reduced from two hours to one on two of the eight sitting days.[16] A recommendation from the Standing Orders Committee in 1986 that proposals be received only on broadcast days was not dealt with before the simultaneous dissolution the following year and did not resurface thereafter.[17]

The 1989 revision resolved a longstanding anomaly, possibly resulting from a combination of common practices to either avoid or force a result by withdrawing the motion, moving the closure on it or talking it out until the business of the day could be called on. By longstanding practice, the question was not put in this last circumstance. The explanatory notes tabled with both drafts of the 1989 revision suggested that “it would be more rational for the question to be put when the time expires”. The revised standing order made this explicit. As a matter of practice, the question is also put if an urgency motion is interrupted by any fixed-time business (such as General Business commencing not later than 4.30 p.m. on Thursdays).

The only other change of substance was the insertion of a provision to deal with the situation of two or more proposals being lodged simultaneously. In that situation, the proposal to be reported is determined by lot. This was a codification of existing practice and had been put to the test earlier in 1989 when independent Senator Irina Dunn (NSW) had submitted an urgency motion at the same time as 25 opposition senators submitted identical urgency motions. President Sibraa explained to the Senate:

I gave consideration to whether only one of the proposals submitted by Opposition senators should be included in the ballot held to determine which matter of urgency is to proceed when two or more proposals are submitted at the same time. I decided that, on a strict interpretation of the existing practice and to properly have regard to the rights of individual senators, all the proposals should be included in the ballot. Accordingly, a ballot was held in the presence of the Deputy Opposition Whip, Senator Knowles, a representative of Senator Dunn and the Clerk of the Senate.

Not surprisingly, an opposition motion was selected.[18]

Finally, in 1997, changes resulting from the adoption of the revised routine of business in 1994 were incorporated into the standing order. These changes affected paragraph (3), the point in the routine at which a proposal is reported, and paragraph (7), the time available for the debate. Because the new routine recognised a new element of business, namely, taking note of answers to questions without notice, for which 30 minutes was allowed, the time available for proposals under SO 75 was reduced as a trade off. If there were no motions to take note of answers, then a time limit of 90 minutes applied but this was reduced to 60 minutes if motions were moved to take note of answers.

It has become common practice for informal arrangements to be reached between the whips as to the division of times between representatives of the various groups in the Senate. If these arrangements are communicated to the chair, the following announcement is made:

I understand that informal arrangements have been made to allocate specific times to each of the speakers in today’s debate. With the concurrence of the Senate, I shall ask the Clerks to set the clock accordingly.

If no such arrangements are communicated or made, the clock is set to the standard time of 10 minutes per speaker.

In practice, proposals under SO 75 are not received before 8.30 a.m. on a sitting day to ensure that all senators have a fair and equal opportunity to submit a proposal. The usual forms for proposals are as follows:

- for a matter of public importance

Dear Madam/Mr President

Pursuant to standing order 75, I propose that the following matter of public importance be submitted to the Senate for discussion:

“(here specify the matter of public importance)”.

Yours sincerely

(……………………………)

Senator for the State of ……

- for a matter of urgency

Dear Madam/Mr President

Pursuant to standing order 75, I give notice that today I propose to move “That, in the opinion of the Senate, the following is a matter of urgency:

(Here specify the matter of urgency)”.

Yours sincerely

(……………………………)

Senator for the State of ……

It is not in order for a proposal under SO 75 to contain a substantive motion.