142 Limitation of debate on bills

-

When a motion for leave to introduce a bill is called on, or when a message is received from the House of Representatives transmitting a bill for concurrence, or at any other stage of a bill, a minister may declare that the bill is an urgent bill, and move that the bill be considered an urgent bill, and such motion shall be put forthwith without debate or amendment.

-

If that motion is agreed to, a minister may forthwith, or at any time during any sitting of the Senate or committee, but not so as to interrupt a senator who is speaking, move a further motion or motions specifying the time which (exclusive of any adjournment or suspension of sitting, and notwithstanding anything contained in any other standing or other order) shall be allotted to all or any stages of the bill, and an order with regard to the time allotted to the committee stage of the bill may, out of the time allotted, apportion time to particular clauses, or to particular parts of the bill.

-

On such further motion or motions with regard to the allotment of time, debate shall not exceed 60 minutes, and in speaking, a senator shall not exceed 10 minutes, and if the debate is not sooner concluded, forthwith upon the expiration of that time the President or the chairman shall put any questions on any amendment or motion already proposed from the chair.

-

For the purpose of bringing to a conclusion any proceedings which are to be brought to a conclusion on the expiration of the time allotted under any motion passed under the provisions of this standing order, the President or the chairman shall at the time appointed put forthwith the question on any amendment or motion already proposed from the chair, and, in the case of the consideration of any bill in committee, shall then put any clauses and any amendments and new clauses and schedules, copies of which have been circulated among senators 2 hours at least before the expiration of the allotted time, and any other question requisite to dispose of the business before the Senate or committee, and no other amendments, new clauses or schedules shall be proposed.

-

The motion that the question be now put shall not be moved in any proceedings in respect of which time has been allotted under this standing order.

-

Where a time has been specified for the commencement of proceedings under this standing order, when the time so specified has been reached the business then before the Senate or committee shall be postponed forthwith and the consideration of the urgent bill proceeded with, and all steps necessary to enable this to be done shall be taken accordingly.

Amendment history

Adopted: 3 March 1926, J.45, as SO 407B

Amended:

- 2 December 1965, J.427 (to take effect 1 January 1966) (amendment of the special majority formerly required to support a motion to declare a bill urgent)

- 22 November 1999, J.2008–09 (paragraph (4) amended to allow the question to be put on non-government as well as government amendments at the expiration of time)

1989 revision: Old SO 407B restructured from four to six paragraphs and renumbered as SO 142; language modernised and expression considerably streamlined; the requirement for a special majority in support of a motion to declare a bill an urgent bill abolished; references to the non-application of certain standing orders replaced with a clear statement that the closure could not be moved under a limitation of time

Commentary

Events leading up to the adoption of the guillotine in 1926 followed the introduction of time limits in 1919 (see SO 189) and the use of the gag in 1920 on the War Precautions Act Repeal Bill. In the sessions of 1923–24 and 1925 the use of the gag by government senators became more common, including in association with all–night or weekend sittings when tempers were most likely to fray. In debate on the Appropriation Bill 1923–24, for example, which occurred through the night of 22–23 August 1923, the gag was moved eight times and once more on the Income Tax Assessment Bill [No. 2] which followed it. The gag was also used the following day on the River Murray Waters Bill.[1] In July 1925, the gag was moved 6 times on the Immigration Bill and in August, in relation to the Peace Officers Bill, considered on a Saturday and continuing the following Monday, the gag was moved 21 times.[2]

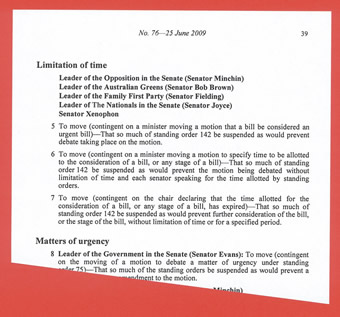

Contingent notices such as these allow the various restrictions in SO 142 to be overcome, provided a majority of the Senate supports these courses of action

The gag is a crude device to truncate debate. If a gag motion is agreed to, the main question is required to be put without further debate. While it may have some efficacy for dealing with a single question, it is an ineffective means of dealing with bills which may contain many clauses to which there may be many proposed amendments and therefore many questions to be determined. After 21 gag motions were required during consideration of the Peace Officers Bill in 1925, the Senate referred to the Standing Orders Committee the formulation of additional standing orders to provide for the limitation of debate on bills declared as urgent bills, otherwise known as a “guillotine”.[3] The Senate divided on the motion which was carried by 17 votes to 8, Senator Gardiner being amongst those voting “No”. When the Standing Orders Committee report was debated on 3 March 1926, the Leader of the Government, Senator Pearce (Nat, WA), rationalised the guillotine as a more just device than the gag in the following terms:

… if an active minority desires to block the passage of a measure, which it knows the majority wishes to pass, it can occupy practically the whole time allowed for debate, and the only weapon in the hands of the Government is the “gag”, by which the mouths of its own supporters are shut, and the whole field of debate is in the hands of those who are opposed to the measure. Under the guillotine provision a reasonable time is allowed for the discussion of a bill or motion, and, that time having been fixed, each side alternately can put forward its speakers, and all aspects of the matter can be debated. This is fair to the majority as well as to the minority. It is much fairer than the application of the “gag”, which often excludes useful contributions, and permits what is practically a waste of time by honourable senators who merely talk against time.[4]

Senator Gardiner spoke against the adoption of the guillotine, referring to his own role in delaying the Peace Officers Bill, but the motion was carried by 20 votes to 7 and the guillotine became part of the Senate’s procedures, just as it was part of the procedures in much larger houses such as the House of Commons and the House of Representatives.[5]

Contingent notices such as these allow the various restrictions in SO 142 to be overcome, provided a majority of the Senate supports these courses of action

The original standing order contained a requirement for any motion declaring a bill to be an urgent bill to be supported “without dissentient voice” or otherwise carried by an affirmative vote of not less than 13 senators. Until 1949, this number represented a quorum plus one and was therefore designed to protect the minority. It was updated to 21 in 1965, long after the Senate increased to 60 in 1949, but was not updated when the size of the Senate increased again in 1974 and 1984. This and several other requirements for special majorities were removed in the course of the 1989 revision as being out of date.[6]

For many years, senators have kept on the Notice Paper contingent notices for the suspension of standing orders to ameliorate the impact of the guillotine. If agreed to, such motions would permit:

-

debate on the motion to declare a bill urgent;

-

unlimited debate on the motion for the allotment of time;

-

unlimited or further specified time for consideration of the urgent bill once the allotted time had expired.

Before 1999, a further contingent notice provided for the suspension of standing orders to enable the question on non-government amendments to be put at the expiration of time. This was designed to circumvent the restriction on the question being put on any amendments other than government amendments at that time. This restriction was regularly waived by leave, however, and in 1999 the Procedure Committee recommended that it be lifted altogether to allow the question to be put on all amendments circulated at least two hours in advance of the time expiring.[7]

For further details on the application of SO 142, see Odgers’ Australian Senate Practice, 12th edition, pp.265–67.