Dr Cameron Hill

Overview: trends, comparisons and

responses

Australia’s Official Development Assistance (ODA) budget will

increase in line with inflation in 2017–18 and 2018–19. However, the Government

has decided to freeze ODA at $4.0 billion in 2019–20 and 2020–21.[1]

These two consecutive freezes—worth an estimated $303 million in savings over

the forward estimates—represent the fifth and sixth cuts, in real terms, to aid

funding since 2013–14.[2] In cumulative terms, the ODA

budget has been cut (or is projected to be cut) by almost one third (32.8 per

cent) since the Gillard Government’s 2013–14 Budget, which represented a high

point for aid funding.[3] The Government has

indicated that the aid program is unlikely to rise in real terms until the

budget returns to surplus.[4]

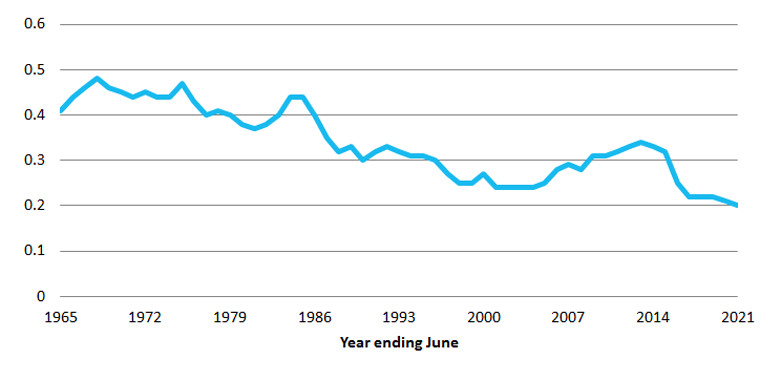

The freezes accelerate Australia’s diminishing aid generosity:

ODA as a proportion of Gross National Income (GNI) will fall to 0.22 per cent

in 2017–18 and to an unprecedented low of 0.20 per cent in

2020–21 (see Figure 1).[5]

Figure 1: Australian ODA/GNI ratio,

1965 to 2021

Source: Development Policy Centre, Australian aid tracker:

trends

Aid is projected to continue to decline as a proportion of (increased)

government outlays, falling to a new recorded low of 0.77 per cent of

government expenditure in 2020–21.[6]

These cuts are also expected to see Australia fall further

down the ladder of developed country donors and well below the current Organisation

for Economic Co-operation and Development ODA/GNI average of 0.32 per cent.[7]

In 2016, Australia ranked 17th out of 29 OECD bilateral donors for aid generosity,

and is projected to fall to 21st in the coming years.[8] Australia is currently

the world’s 13th largest economy.[9]

Although global ODA increased in 2016, Australia is not

alone in cutting aid. The Trump administration has mooted cutting US development

assistance programs by almost one-third, with some of the largest cuts slated

for Australia’s region.[10] In contrast, the UK Conservative

Government has committed to maintaining ODA/GNI at its current level of 0.7 per

cent if re-elected in June 2017.[11]

Allocations for countries and regional programs will remain

largely unchanged in 2017–18 (see Table 1). A nominal $84 million increase

in ODA will be directed to increases in humanitarian assistance, the Middle

East and global health programs.[12] In the Pacific, ODA will

be redirected from the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade to the

Australian Federal Police to help fund policing programs in PNG and the Solomon

Islands.[13]

Table 1: estimated total Australian

ODA by region (AUD million)

| |

2016–17 Budget |

2016–17 outcome |

2017–18 Budget |

| Pacific

(including PNG) |

1 138.4 |

1 126.4 |

1 097.8 |

| Southeast

and East Asia |

887.7 |

892.9 |

883.0 |

| South

and West Asia |

282.8 |

292.0 |

283.9 |

| Africa

and the Middle East |

184.9 |

263.5 |

253.6 |

| Latin

America and the Caribbean |

11.0 |

11.4 |

5.9 |

| ODA

not attributed to regions/countries |

1 322.9 |

1 241.6 |

1 388.1 |

Source: DFAT, Australian

aid budget summary, 2017–18, 9 May 2017.

Non-government organisations and the Opposition have

criticised the latest cuts. The Australian Council for International

Development has stated that the aid budget ‘does not add up to a vision of what

role we want to play in the world’.[14] The Labor Opposition has

described the cuts as ‘at odds with the generous spirit of the Australian

people’ but has not re-committed to its previous 0.5 per cent ODA/GNI target.[15]

Looking ahead: aid, development and

Australia’s international engagement

Beyond the Budget, the Government’s forthcoming foreign

policy white paper, the first since 2003, will consider the role of aid and

development in advancing Australia’s interests and values.[16]

The Prime Minister has also promised a new whole-of-government ‘Pacific

strategy’, the first of its kind.[17] Given Australia’s position

as the leading donor in the Pacific, development issues should feature

prominently.

In 2018, Australia will host a joint summit with the ten leaders

of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).[18]

Australia’s aid to the developing ASEAN states will total almost $800 million

in 2017–18. In addition to security and trade ties, the role of development

cooperation in advancing our relationship with this important regional grouping

will likely be a focus.

Finally, a scheduled 2018 OECD ‘peer review’ of Australia’s

aid program—the first since the abolition of AusAID in 2013 and the implementation

of successive budget cuts—will be an opportunity to assess overall policy

coherence and development effectiveness following a period of significant upheaval

in aid programming and administration.[19]

[1].

Australian Government, Portfolio

budget statements 2017–18: budget related paper no.1.9: Foreign Affairs and

Trade Portfolio, p. 20; J Bishop (Minister for Foreign Affairs), 2017

foreign affairs budget, media release, 9 May 2017.

[2].

S Howes, ‘A small

target budget with a sting in the tail’, DevPolicy, Development

Policy Centre blog, 9 May 2017.

[3].

Ibid. While actual aid expenditure was higher in 2012–13, the 2013–14

Budget further increased ODA. This increase was subsequently cut in the 2013–14

MYEFO.

[4].

F Hunter, ‘Julie

Bishop says foreign aid will stay in freezer until budget reaches surplus’,

The Sydney Morning Herald, online, 12 May 2017.

[5].

Development Policy Centre, Australian aid tracker:

trends, Development Policy Centre website. Recorded data for ODA goes

back to 1962.

[6].

Ibid.

[7].

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Development

aid rises again in 2016 but flows to poorest countries dip, media

release, 11 April 2017.

[8].

Development Policy Centre, Australian aid tracker:

comparisons, Development Policy Centre website; ‘Julie Bishop says

foreign aid will stay in freezer until budget reaches surplus’, op. cit.

[9].

World Bank, Data: GDP

ranking, World Bank website.

[10].

C Hill, ‘A

different kind of ‘pivot’: the Trump administration’s proposed aid cuts and

Australia’s region’, FlagPost, Parliamentary Library blog, 8 May 2017.

[11].

G Parker, ‘Theresa

May says Tories will keep 0.7% overseas aid target’, Financial Times,

online, 22 April 2017.

[12].

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade, Australian

aid budget summary, 2017–18, 9 May 2017, pp. 10–11.

[13].

C Barker, ‘Law

enforcement overview’, Budget review 2017–18, Research paper series,

2016–17, Parliamentary Library, Canberra, 2017.

[14].

Australian Council for International Development, Aid

budget bounces along the bottom, media release, 9 May 2017.

[15].

P Wong (Shadow Minister for Foreign Affairs) and C Moore (Shadow Minister

for International Development and the Pacific), Aid

funding plunges to new low as Bishop rolled again, media release, 8 May

2017.

[16].

C Hill, ‘Australian

foreign policy in 2017: a year of delivery?’, FlagPost, Parliamentary

Library blog, 28 March 2017.

[17].

M Turnbull (Prime Minister), Remarks

at Pacific island Forum—Micronesia, transcript, 9 September 2016.

[18].

M Turnbull (Prime Minister), ASEAN-Australia

special summit 2018, media release, 23 February 2017.

[19].

OECD, Australia—DAC

peer review of development co-operation, OECD website.

All online articles accessed May 2017.

For copyright reasons some linked items are only available to members of Parliament.

© Commonwealth of Australia

Creative Commons

With the exception of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms, and to the extent that copyright subsists in a third party, this publication, its logo and front page design are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Australia licence.

In essence, you are free to copy and communicate this work in its current form for all non-commercial purposes, as long as you attribute the work to the author and abide by the other licence terms. The work cannot be adapted or modified in any way. Content from this publication should be attributed in the following way: Author(s), Title of publication, Series Name and No, Publisher, Date.

To the extent that copyright subsists in third party quotes it remains with the original owner and permission may be required to reuse the material.

Inquiries regarding the licence and any use of the publication are welcome to webmanager@aph.gov.au.

This work has been prepared to support the work of the Australian Parliament using information available at the time of production. The views expressed do not reflect an official position of the Parliamentary Library, nor do they constitute professional legal opinion.

Any concerns or complaints should be directed to the Parliamentary Librarian. Parliamentary Library staff are available to discuss the contents of publications with Senators and Members and their staff. To access this service, clients may contact the author or the Library‘s Central Enquiry Point for referral.